1.Bespoke’s S&P 500 Sector Weightings—

Energy 2019 Less Than 5%

Fri, Sep 20, 2019

S&P 500 sector weightings are important to

monitor. Over the years when weightings have gotten extremely lopsided

for one or two sectors, it hasn’t ended well. Below is a table showing

S&P 500 sector weightings from the mid-1990s through 2016. In the

early 1990s before the Dot Com bubble, the US economy was much more evenly

weighted between manufacturing sectors and service sectors. Sector

weightings were bunched together between 6% and 14% across the board. In

1990, Tech was tied for the smallest sector of the market at 6.3%, while

Industrials was the largest at 14.7%. The spread between the largest and

smallest sectors back then was just over 8 percentage points.

The Dot Com bubble completely blew up the balanced economy, and looking back

you can clearly see how lopsided things had become. Once the Tech bubble

burst, it was the Financial sector that began its charge towards

dominance. The Financial sector’s sole purpose is to service the economy,

so in our view you never want to see the Financial sector make up the largest

portion of the economy. That was the case from 2002 to 2007, though, and

we all know how that ended.

Unfortunately we’ve begun to see sector weightings get extremely out of

whack once again.

2.Total Global Oil Production-Millions of Barrels Per Day

Energy makes up less than 5% of the S&P 500 index’s market cap, the lowest level in at least 40 years.

What the Saudi Attacks Mean for Energy Investors By Avi Salzman

3.Why the Saudi Attack Did Not Put Markets in Chaos?

Netted out across the US, imports and exports of crude oil and petroleum products are now nearly in balance. Net imports (imports minus exports) of crude oil and petroleum products in June were down to merely 506,000 bpd. The US is on track to become a net exporter in 2020:

Drama in the Oil Markets, But This Isn’t 2007 Anymore

by Wolf Richter • Sep 16, 2019 • 167 Comments • Email to a friend

How the US shale boom changed the equation. If the attack on Saudi oil facilities had occurred in 2007, it would have caused chaos in the US economy.

Full Read

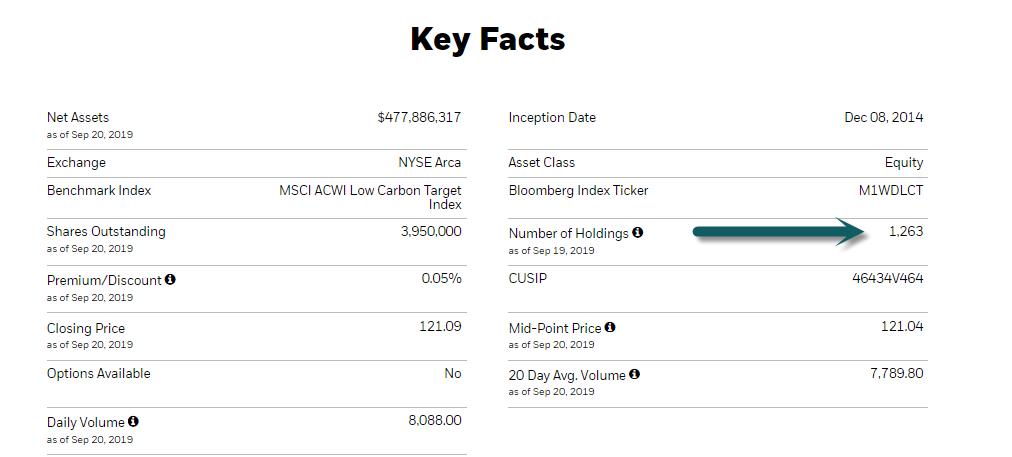

4.Low Carbon Target ETFs.

LOWC-MSCI Low Carbon Target ETF

- Seeks to offer reduced exposure to carbon emissions and fossil fuel reserves and full market participation for investors conscious of carbon as a risk premia

- LOWC’s Index reweights the securities in the MSCI ACWI Index to favor companies with lower carbon emissions and fossil fuel reserves within a tracking error target constraint of 30 basis points relative to the MSCI ACWI Index

- This index includes large and mid-cap stocks across developed and emerging market countries

1500 Holdings

https://us.spdrs.com/en/etf/spdr-msci-acwi-low-carbon-target-etf-LOWC

CRBN-MSCI Low Carbon Target ETF

1200 holdings

https://www.ishares.com/us/products/271054/ishares-msci-acwi-low-carbon-target-etf

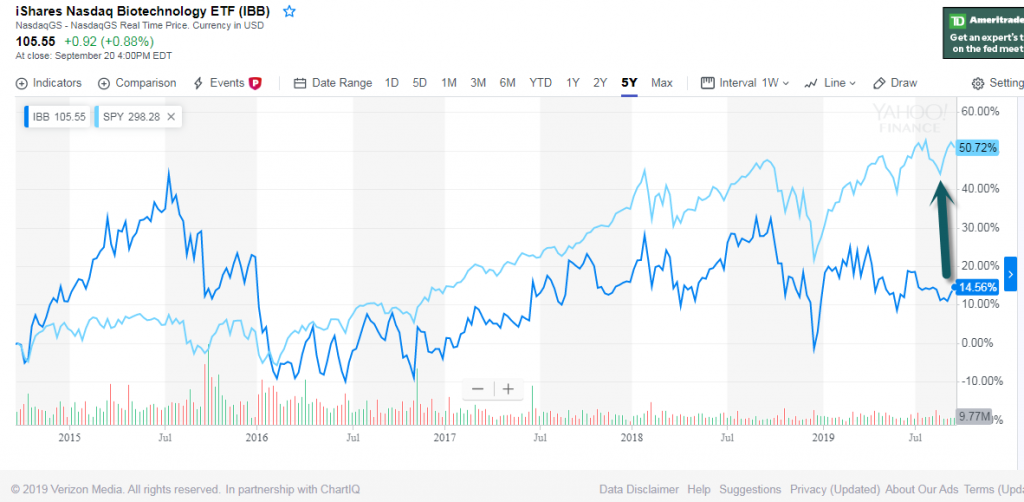

5.Biotech Huge Underperformer for 5 Years.

IBB Biotech ETF +14.5% VS. S&P 50% -5 year chart

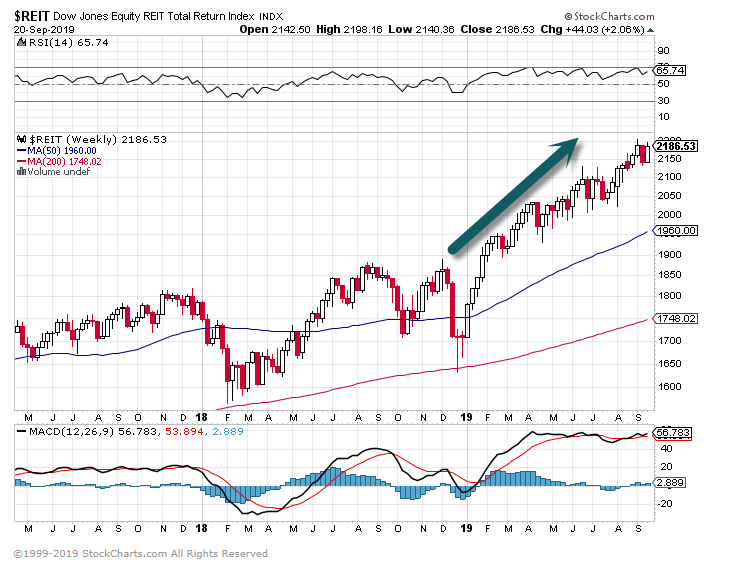

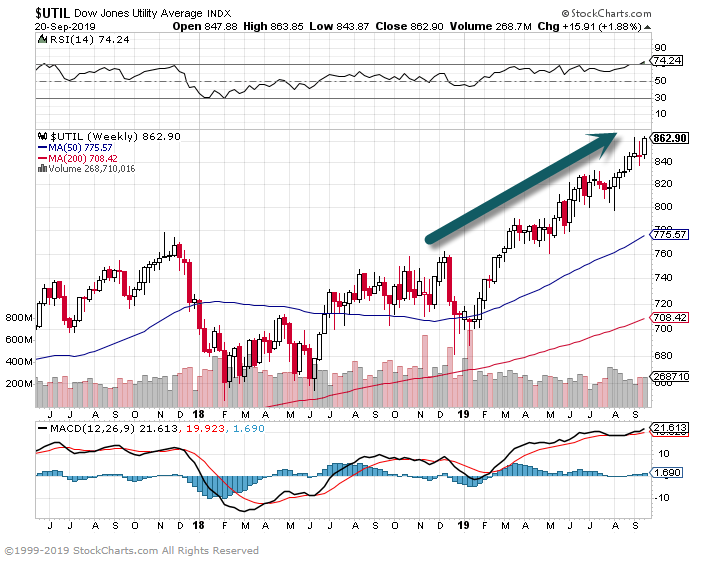

6.Update Two Interest Rate Sensitive Sectors.

Ed Yardeni in Barrons

Two interest-rate-sensitive and defensive sectors have seen their forward P/Es increase sharply. The S&P 500 Real Estate sector’s P/E, at 43.9, is 5.1 points higher than it was this time last year, and the S&P 500’s Utilities sector’s forward P/E is almost 3.0 points higher at 19.6—a record high dating back nearly 25 years.

REITS 44x forward earnings

Utilities forward P/E 25 year high

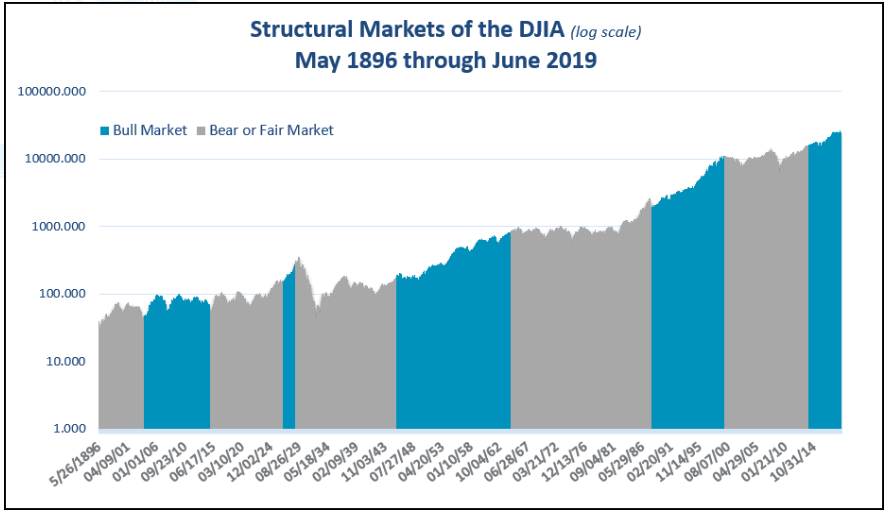

7.Structural Bull Market History for Dow.

Nasdaq Dorsey Wright.

A long-term perspective of the Dow Jones Industrial Average DJIA since 1896 reveals the reality that there are extended periods of time in which the US equity market will trend generally upwards and also long periods of time where the market will instead stagnate or move generally lower. There have been nine such alternating cycles completed since 1896, with each averaging 14 years.

https://oxlive.dorseywright.com/research/bigwire

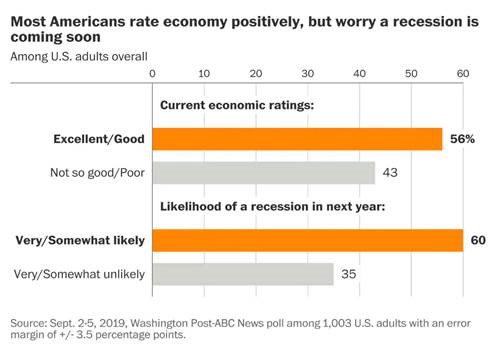

8.Six in 10 Americans expect a recession and higher prices

Source: Washington Post

Found at Barry Ritholtz Blog

9.Will America’s massive debt really doom us?

Ken Fisher, Special to USA TODAYPublished 7:03 a.m. ET Sept. 22, 2019

The U.S. national debt and deficit have become buzzwords for the 2020 election. But what’s the difference? Just the FAQs, USA TODAY

CONNECTTWEETLINKEDINCOMMENTEMAILMORE

America’s massive debt will doom us. That’s common wisdom, but wrong.

In Manhattan, a giant clock displays not only the total — almost $23 trillion for now — but your share, ticking up every second. Pundits say it’s trouble. But U.S. debt fears have lurked forever and those troubles are no closer now than decades ago. In some ways, they’re further off.

Here’s how to see that, using tools that show when debt truly becomes problematic.

The $23 trillion total seems jaw-dropping, but says little about what really matters: How readily Uncle Sam can pay the piper.

Pundits cite our debt-to-GDP ratio as evidence of a debt addiction. With $21 trillion of GDP, that ratio is 103% — lower than Italy’s and Japan’s, but higher than Germany’s and Britain’s. Debt topping GDP sounds dire. But that’s misleading. The federal government itself owns more than a quarter of U.S. debt, money the government essentially owes itself. It’s an accounting entry. As an asset and a liability, it effectively cancels out. Otherwise, net outstanding public debt is $16.7 trillion— 76% of GDP. That’s still unimportant.

America’s massive debt will doom us. That’s common wisdom, but wrong. (Photo: Mike Rosiana / Getty Images)

Why? Because debt-to-GDP is apples-to-nonsense. Debt piles up year after year. GDP is an estimate of economic activity in a single year, ignoring long-term assets that back a country’s liabilities. America’s hard assets via Federal Reserve data — business equity, real estate, fixed income holdings, cash — amount to $175.3 trillion, 10 times public debt. But again, that’s irrelevant.

Government solvency isn’t about paying off debt. It’s about affording interest payments and rolling over maturing bonds. Currently, annual U.S. interest payments represent just 9.8% of tax revenues, lower than any time in the 1980s and 1990s, when they peaked at 18.4%. If debt didn’t doom us then, why would it now?

Naysayers often rebut that by saying it’s all thanks to low-interest rates, which may reverse. Fair point. A 30-year Treasury bought 30 years ago carried 8.15% interest. Today, we can refinance at about 2%, a heckuva deal. Plus,10-year debt is cheaper too. But rates only matter to the government’s finances at issuance. Since America’s debt averages about six years in maturity, short-term rate wiggles don’t create danger.

\For debt to become a problem, Uncle Sam must spend like a drunken sailor for decades (which he may). Or interest rates must skyrocket and stay there, with the country’s interest payments ballooning and investors demanding more return for more risk. Do you see any signs of that now? Maybe someday. But not any time soon.

Pockets of debt trouble do exist around the world. To see them, look to markets. Compare low-default-risk Treasury rates to similar-maturity rates from other issuers — it’s called a credit spread. For example, South Africa and Turkey are both suffering significant debt pressure. How do you know? America can borrow for 10 years at 1.62%. Investors demand 8.82% to lend to South Africa. Turkish rates are 15.18%.

Get the The Daily Money newsletter in your inbox.

A collection of articles to help you manage your finances like a pro.

Delivery: Mon – Fri

Your Email

Use that same approach to assess corporate debt. Corporate America doesn’t have a debt problem, despite frequent fears that hinge on its debt total alone. Overall corporate spreads have declined this year. To be sure, oil price pressures have squeezed the tiniest U.S. shale-oil drillers. Bonds of less-creditworthy drillers now yield 10.3%, up from 7.4% a year ago. That rise — while rates overall plunged — signals trouble. No shock: Driller defaults are climbing.

But while problems with debt darken isolated patches, debt doom doesn’t loom over America.

Ken Fisher is founder and executive chairman of Fisher Investments, author of 11 books, four of which were New York Times bestsellers, and is No. 200 on the Forbes 400 list of richest Americans. Follow him on Twitter: @KennethLFisher

The views and opinions expressed in this column are the author’s and do not necessarily reflect those of USA TODAY.

https://www.usatoday.com/story/money/columnist/2019/09/22/debt-debt-doom-america/2384550001

10.Why Asking for Advice Is More Effective Than Asking for Feedback

JORG GREUEL/GETTY IMAGES

You just gave a great first pitch to a major client and landed an invitation to pitch to their senior leaders. Now you want a second opinion on your presentation to see if there’s anything you can improve. What do you do?

Conventional wisdom says you should ask your colleagues for feedback. However, research suggests that feedback often has no (or even a negative) impact on our performance. This is because the feedback we receive is often too vague — it fails to highlight what we can improve on or how to improve.

Our latest research suggests a better approach. Across four experiments — including a field experiment conducted in an executive education classroom — we found that people received more effective input when they asked for advice rather than feedback.

In one study, we asked 200 people to offer input on a job application letter for a tutoring position, written by one of their peers. Some people were asked to provide this input in the form of “feedback,” while others were asked to provide “advice.” Those who provided feedback tended to give vague, generally praising comments. For example, one reviewer who was asked to give feedback made the following comment: “This person seems to meet quite a few of the requirements. They have experience with kids, and the proper skills to teach someone else. Overall, they seem like a reasonable applicant.”

However, when asked to give advice on the same application letter, people offered more critical and actionable input. One reviewer noted more specific action items: “I would add in your previous experience tutoring or similar interactions with children. Describe your tutoring style and why you chose it. Add what your ultimate end goal would be for an average 7 year old.”

In fact, compared to those asked to give feedback, those asked to provide “advice” suggested 34% more areas of improvement and 56% more ways to improve.

In another study, we asked 194 full-time employees in the U.S. to describe a colleague’s performance on a recent work task. These tasks ranged from “putting labels on items” to “creating new marketing strategies.” Then, we asked employees to give feedback or advice on the work performance they just described. Once again, those who were asked to provide feedback gave less critical and actionable input (e.g. one wrote, “They gave a very good performance without any complaints related to his work”) than those asked to provide advice (e.g. one wrote, “In the future, I suggest checking in with our executive officers more frequently. During the event, please walk around, and be present to make sure people see you”).

We further replicated these findings in a field experiment using instructor evaluations. In an end-of-course evaluation, we asked 70+ executive education students from around the world to provide either feedback or advice to their instructors. Again, advice more frequently contained detailed explanations of what worked and what didn’t, such as: “I loved the cases. But I would have preferred concentrating more time on learning specific tools that would help improve the negotiation skills of the participants.” Feedback, in contrast, often included generalities, such as “This faculty’s content and style of teaching was very good.”

Why is asking for advice more effective than asking for feedback? As it turns out, feedback is often associated with evaluation. At school, we receive feedback with letter grades. When we enter the workforce, we receive feedback with our performance evaluations. Because of this link between feedback and evaluation, when people are asked to provide feedback, they often focus on judging others’ performance; they think more about how others performed in the past. This makes it harder to imagine someone’s future and possibly better performance. As a result, feedback givers end up providing less critical and actionable input.

In contrast, when asked to provide advice, people focus less on evaluation and more on possible future actions. Whereas the past is unchangeable, the future is full of possibilities. So, if you ask someone for advice, they will be more likely to think forward to future opportunities to improve rather than backwards to the things you have done, which you can no longer change.

To document this effect, we ran another study that was very similar to our first. In this experiment, we again asked hundreds of people to provide feedback or advice on a peer’s job application. But this time, we also asked feedback providers to shift their focus toward “developing the writer.” When removed from an evaluation mindset, by focusing more on developing the recipient, feedback providers were just as critical and actionable in their input as advice providers.

Is asking for feedback always a worse strategy than asking for advice? Not necessarily.

Sometimes soliciting feedback may be more beneficial. People who are novices in their field typically find critical and specific input less motivating — in part because they don’t feel like they have the basic skills necessary to improve. So for novices, it might be better to ask for feedback, rather than advice, to receive less demotivating criticism and more high-level encouragement.

Organizations are full of opportunities to learn from peers, colleagues, and clients. Despite its prevalence, asking for feedback is often an ineffective strategy for promoting growth and learning. Our work suggests this is because when givers focus too much on evaluating past actions, they fail to provide tangible recommendations for future ones. How can we overcome this barrier? By asking our peers, clients, colleagues, and bosses for advice instead.

Jaewon Yoon is a PhD student in the organization behavior program at Harvard Business School. Her research focuses on time communication and feedback exch