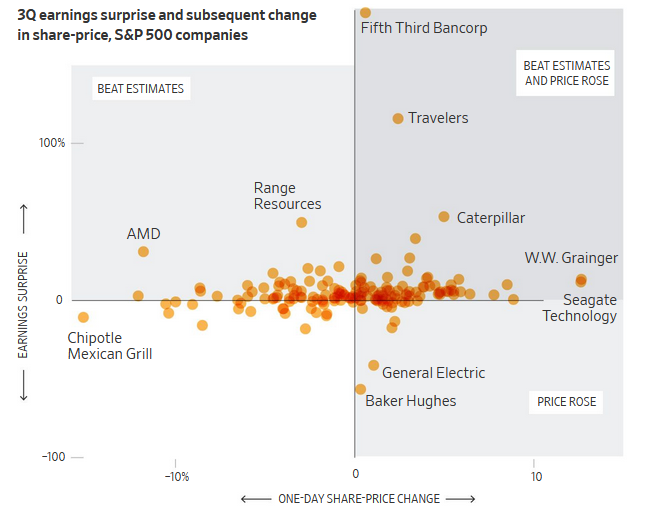

1.75% of S&P Beating Earnings.

BIG SPLASH– Earnings are making their biggest splash in the stock market in years – Investors are sharply bidding up the shares of companies that beat expectations—and appear more willing to overlook some of the misses—helping to pull the stock market out of its recent lull. More than three-quarters of the 358 companies in the index that reported through Friday have beaten estimates. And 66% have risen in subsequent trading sessions, a five-year high.

Shares of companies that topped forecasts rose an average of 2% in the two days after reporting results, beating the five-year average of 1%, according to data compiled by FactSet. Those that fell short have averaged a 2.1% pullback, below the half-decade average of 2.6%, WSJ reports

From Dave Lutz at Jones Trading

2.Leveraged-Loan Downgrades Spike, Collateralized Loan Obligations Get Cold Feet, Selloff in B-Rated Loans Ensues

by Wolf Richter • Nov 4, 2019 • 0 Comments • Email to a friend

“Sell first, ask questions later.”

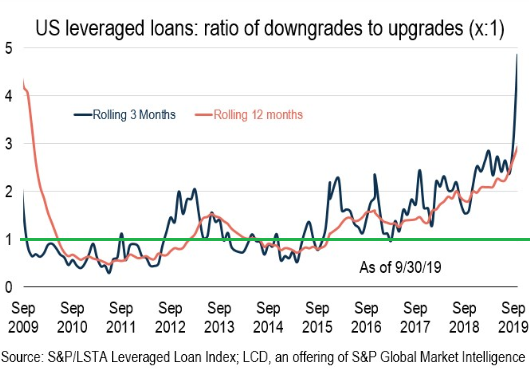

The $1.2-trillion US leveraged loan market is starting to get downgrade-indigestion. So far this year through October 11, of the 1,460 leveraged loans in the S&P/LSTA Index, 282 issues were downgraded, already exceeding the 244 downgrades for the entire year of 2018, and blowing past the 33 downgrades in 2017, according to LCD of S&P Global Market Intelligence.

On a rolling three-month basis, the ratio of downgrades-to-upgrades spiked to 4.9, by far the highest ratio since the Financial Crisis. In the chart below via LCD, a value greater than 1 (horizontal green line) means downgrades exceed upgrades. A value blow 1 means upgrades exceed downgrades.

Collateralized Loan Obligations get cold feet.

The hot-button issue at the moment with leveraged loans is a one-step downgrade from B-, or a 2-step downgrade from B (“highly speculative”), to triple-C (“substantial risk,” see my cheat sheet for corporate bond and loan credit ratings by ratings agency).

It’s a hot-button issue because managers of Collateralized Loan Obligations (CLOs) currently purchase about three-quarters of the leveraged loans that banks are syndicating and hold about 55% to 60% of all leveraged loans outstanding, according to LCD. But CLOs have limits as to how much in CCC-or-below-rated loans they can hold.

Read Full Story

3.Money Still Pouring into Private Capital Funds.

David Haarmeyer Linkedin

https://www.linkedin.com/in/david-haarmeyer-026752/

4.Volume of Trading in Privately Held Shares Growing 100% Per Year.

You Want a Piece of That Hot Pre-IPO? It’s Getting Easier.By Eric J. Savitz

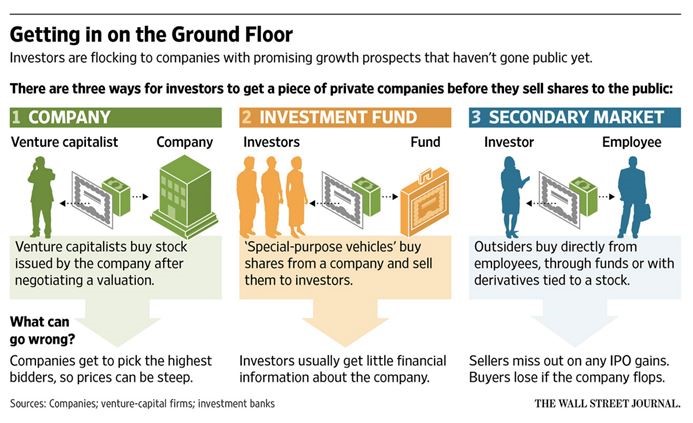

While the IPO market has temporarily ground to a halt, there are still opportunities for the intrepid investor to buy shares of hot companies like AirBnB, Snowflake Computing and Impossible Foods that haven’t actually offered stock to the general public just yet.

That’s what Forge does—arranges trades in pre-IPO shares. The San Francisco-based company is one of several players in this growing niche market, allowing long-standing insiders and venture investors to get out while creating a path for institutional and high net worth individual investors to bet on fast growing privately-held companies.

The fact that Forge and rival SharesPost even exist reflects the dramatic changes that have unfolded in the last few years in initial public offerings. Companies are staying private longer—10 years or more from inception, in many cases—and often generating hundreds of millions of revenue before filing.

That leads to higher market caps at IPO—many tech companies have been launching with valuations in the billions. Meanwhile, with most IPOs, insiders can’t trade on day one due to lock-up restrictions, leading to stocks with big market caps but thin floats and wildly trading shares.

That combination leads to frustration for both early investors, who can’t immediately sell shares, and for institutions who want to own the stocks but can’t get enough initially to establish meaningful positions.

All of that helps explain the growing interest in Forge. There have been transactions in pre-IPO stocks for many years, but the friction has historically been high, requiring companies to sign off on any transactions in their shares, and with challenges in matching buyers and sellers in a way that allows for efficient price discovery. But as companies stay private longer, shareholders are pushing harder for an opportunity to sell shares—and institutions are eager to get involved in high-growth opportunities ahead of an initial offering.

Forge Chief Executive Officer Kelly Rodriques says his company has arranged about $2 billion in trades over the past 18 months, working with most of the top 100 privately-held, venture-backed companies as ranked by valuation. He says Forge will do about $100 million in revenue in 2020.

Rodriques says the volume of trading in privately held shares is growing at better than 100% a year. “Today you are seeing more company-structured liquidity programs for their employees, and you are also seeing more venture capital investors selling positions while companies are still private,” he said in a recent interview with Barron’s. “The traditional IPO ‘pop’ is now happening 18 months before companies actually become a public company.”

https://www.pensco.com/blog/holding-a-pre-ipo-company-in-your-self-directed-ira#.XcFhnuhKiUk

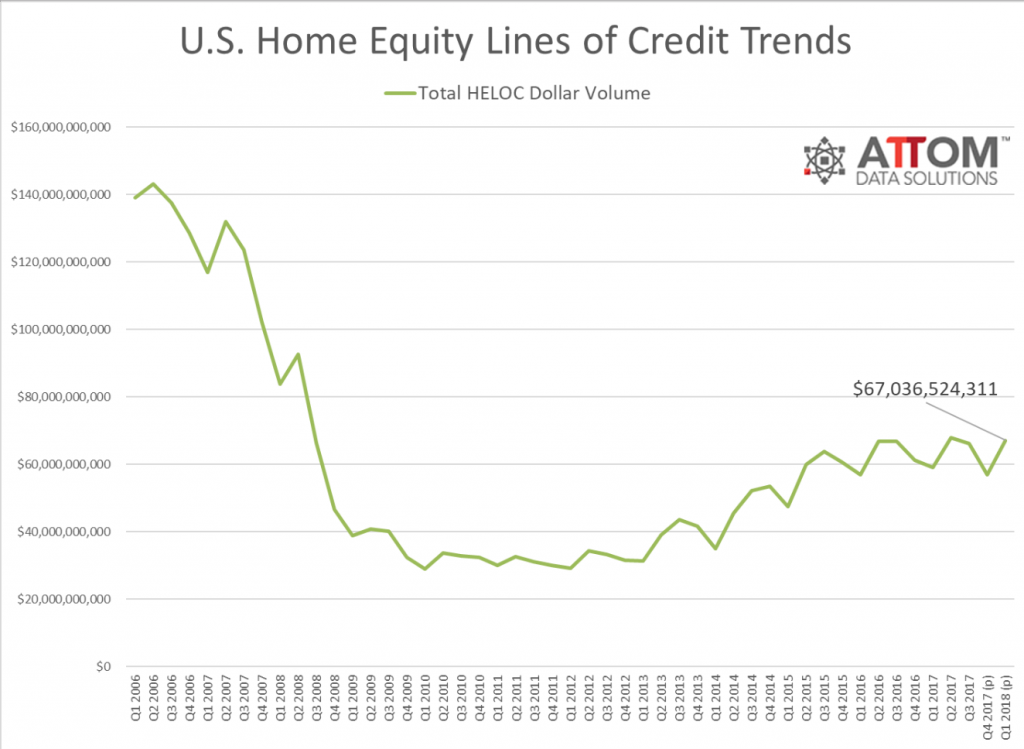

5.HELOCs Half of 2008

http://static.realtytrac.com/images/reportimages/HELOC_Origination_Historical_Q1_2018.png

HELOCs are so 2007; Americans aren’t using homes as piggy banks anymore

The home equity line of credit, or HELOC, has become less popular since the housing crash and Great Recession.

(Getty Images)

By GWEN EVERETT, SHAHIEN NASIRIPOURBLOOMBERG

NOV. 3, 2019

3 AM

A once-popular loan Americans use to finance home renovations and college tuition is slowly dying, slashing a lucrative source of revenue for the nation’s largest banks.

Home equity lines of credit, open-ended loans that homeowners tap for cash using their properties as collateral, exploded in the run-up to the housing crash a decade ago, doubling in volume from 2003 to 2006, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

Rapidly climbing property prices led homeowners to use their homes as piggy banks, fueling consumer spending.

But a resurgent housing market after the Great Recession hasn’t brought with it a return to HELOCs, as they’re commonly known.

Home equity lines have fallen by almost half in the last decade, New York Fed data show. The loans, which constituted 5% of the nation’s banking assets in 2009, now account for less than 2%, according to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp.

Record levels of home equity — spurred by soaring home prices and stagnant mortgage borrowing — haven’t prompted households to use a ready resource as a way to fund big-ticket purchases or home improvements. Finance executives have spent years researching the issue, commissioning surveys and studies to figure out how to jump-start a business that had always been a reliable and relatively low-risk source of earnings.

Fallout from the housing bubble appears to have had a lasting effect on consumers’ willingness to keep using their homes as ATMs. Just 4% of households had an open home equity line in 2016, according to the Federal Reserve’s most recent comprehensive survey of households’ finances, a far cry from the 10% that annually borrowed against the equity in their homes during the 2000s.

“The HELOC market has been in decline since 2008,” said Otto Pohl, a spokesman at Figure, a financial technology firm that offers a type of HELOC. In the “bubble years,” Pohl said, banks almost as a matter of course added home equity lines along with a borrower’s initial mortgage.

Those days are gone.

At Bank of America Corp., the nation’s second-laregest bank by assets, HELOCs produced $552 million of interest income in the third quarter, down two-thirds from a decade ago. Interest rates on the loans were the third-highest among the lender’s various types of assets, trailing only credit cards and a catch-all category called “other.”

U.S. homeowners collectively had $6.3 trillion of housing equity they could borrow against as of June, according to analytics firm Black Knight Inc., more than double the $2.6 trillion total in 2009.

Finance industry executives cite three culprits they think are probably responsible for the gradual demise of HELOCs: an unusual trend in interest rate spreads, easy access to unsecured personal loans from online lenders and psychological scars from the housing bust.

Home equity lines function like credit cards, in that lenders set a maximum amount that homeowners can borrow at any one time. Also like credit cards, they’re based on the prime rate, with lenders charging a bit extra depending on a borrower’s creditworthiness. The prime rate, now at 5%, moves with the federal funds rate set by the Fed.

That’s more expensive than the typical 30-year mortgage, an interest rate that generally tracks the yield on the 10-year Treasury note. The average rate on a new HELOC was 6.45% as of Sept. 30, according to Informa Financial Intelligence. Borrowers looking to exchange equity for cash in a refinancing are being offered an average rate of 3.99%.

When mortgage rates are at least 1 percentage point lower than the rate on HELOCs, borrowers looking to pull equity from their homes typically opt for a cash-out refinancing over a home equity line of credit, said Rutger van Faassen, a vice president of consumer lending at Informa. Add to that the fact that a new mortgage offers a fixed rate instead of the variable rate on a HELOC, and the option becomes even more attractive, he said.

Unsecured personal loans pose another threat to the HELOC business. Many online lenders offer cash in a day, and years of quick turnaround times with their online purchases have conditioned consumers to expect speed when they access credit, said Mark Ford, head of personal lending and card solutions at SunTrust Banks Inc.

Home equity lines require a daunting pile of paperwork and the added headache of a new home appraisal. Typically it takes about 45 days from the date of the application for a borrower to get the cash, according to Informa.

Another obstacle: Borrowers who default on a HELOC, unlike on a personal loan, probably lose their homes.

Lauren Anastasio, a financial advisor at Social Finance Inc., the lender better known as SoFi, said her clients often pick personal loans over HELOCs, despite the higher interest rate, because of the quicker processing time.

A recent survey by J.D. Power found that consumers rated online lenders above home equity providers when it came to customer satisfaction.

Banks are responding. Citizens Financial Group Inc. has reduced its processing times by half, to 35 days, according to Brendan Coughlin, head of consumer deposits at the Providence, R.I.-based bank. Bank of America will allow prospective borrowers to apply online, said Steve Boland, head of consumer lending.

Those efforts may never return the home equity industry to its glory days. Too many homeowners were scarred by the housing bust, and they’ve reduced their borrowing as a result.

Overall household debt has fallen over the last decade, after adjusting for inflation, New York Fed data show. And some borrowers are wary about putting their house on the line, Van Faassen said.

“It’s really the perfect storm,” SoFi’s Anastasio said, citing interest rates and personal loans as key drivers working against HELOCs. Sentiment could change if mortgage rates go up, but for now, “each one of those has an advantage relative to HELOCs.”

6.4 reasons why analysts are cautious on Saudi Aramco’s IPO

PUBLISHED MON, NOV 4 20199:29 AM ESTUPDATED MON, NOV 4 20198:20 PM EST

KEY POINTS

- Saudi Aramco may have finally fired the starting pistol on its initial public offering (IPO), but some analysts still believe investors should think carefully before jumping on board.

- The company, the most profitable in the world, announced Sunday that it’s planning to list on its local stock market, the Tadawul, in December.

- But a lack of details on the listing, which eventually could be the largest on record, has left some analysts cold.

Saudi Aramco may have finally fired the starting pistol on its initial public offering (IPO), but some analysts still believe investors should think carefully before jumping on board.

The company, the most profitable in the world, announced Sunday that it’s planning to list on its local stock market, the Tadawul, in December.

But a lack of details on the listing, which eventually could be the largest on record, has left some analysts cold. And they believe there are plenty of reasons why international investors should be wary.

Lack of details

Aramco said Sunday that “the final offer price, number of shares to be sold and percentage of the shares to be sold will be determined at the end of the book-building period.” The company’s IPO prospectus will be released on November 9.

As such, analysts were left speculating on the finer details of the offering, and these could make all the difference to investor interest, they said.

“Yes, it’s (the IPO has) been confirmed but at this point in time they haven’t really given us a set timetable as to when the transaction is going to get under way or complete,” David Lennox, resources analyst at Fat Prophets, told CNBC Monday.

Previous reports have suggested the kingdom will list 1% to 2% of Aramco on its local stock exchange, and then list another slice on an international exchange at a later date — with a total public sale of roughly 5% of the company. Exchanges in New York, London, Hong Kong and Tokyo have all been vying for the international listing.

Lennox said the valuation could make all the difference to investors. “We’ve also not seen any form of valuation, (although) we’ve seen quite wide numbers from $1 trillion to $2 trillion. We think it’s about $1.4 trillion so you can take your pick,” he said.

“The other factor we don’t know at the moment is just how much of it are they going to float? … So there are a lot of questions we’ve yet to really have answered before one can say we’re going to see this IPO go ahead,” he said.

Dividend

The IPO has been closely-anticipated in the last few years but has been delayed amid oil price volatility, valuation uncertainty, the location of the share listing and geopolitical events such the drone and missile attack in September.

The public listing could be the world’s largest, and if it achieves a valuation of $1.5 trillion Saudi Aramco would far exceed the market capitalization of giants like Apple and Microsoft.

The company said one of its priorities was delivering “sustainable and growing dividends through crude oil price cycles” and that “subject to the board’s discretion after consideration of a number of factors, the board intends to declare aggregate ordinary cash dividends of at least $75.0 billion with respect to calendar year 2020, in addition to any potential special dividends.”

How far that dividend goes will be subject to the amount of shares the company decides to list. “We’ve got the dividend amount but we just don’t know the amount of shares,” Lennox said, noting that “if they issue a bucket load of shares then that dividend amount is not going to go far.”

Meanwhile, analysts at Bernstein noted that it was hard to evaluate a company like Aramco, which it likened to a “monster oil” company.

They cite the fact that Saudi Aramco is the most profitable company in the world — in 2018 its net income was $111 billion, five times bigger than Exxon or Shell. The analysts also note it has an oil reserve life of 52 years and its reserves are the cheapest to extract.

“What’s fair value for a company with access to 201 billion barrels of proven oil reserves, produces 1 in every 8 global oil barrels, is instrumental in supporting oil prices and owns the world’s 4th largest integrated Downstream system pointing at Asia? While we’re used to valuing Big Oil, Aramco is Monster Oil, so this is literally the trillion-dollar question,” Bernstein Senior Analysts Oswald Clint and Neil Beveridge said in a note Monday.

Geopolitics

Geopolitical factors, like Saudi Arabia’s tense relationship with regional rival Iran, could also dampen investor sentiment.

“If you look at it from the perspective of international investors, there are obviously concerns,” Bob Parker, investment committee member at Quilvest Wealth Management, told CNBC’s “Squawk Box Europe” Monday.

“Do you want to invest in a region where the relationship with Iran is fraught?,” he asked. “We’ve also had infrastructure risk related to (the drone and missile attack) a few months ago and a large part of Saudi Aramco infrastructure being damaged.”

In addition, Parker said the valuation might also be a factor adding to international investors’ concerns.

“International investors might say well perhaps I need a discount to warrant my investment in Saudi Aramco … But that discount doesn’t seem to be there,” he said. Parker added that he also believed oil prices were going to be subject to downward pressure.

“All of those factors I think means that this is going to be a difficult IPO,” he warned.

Oil prices

Oil prices slumped in mid-2014 amid a glut in global supply and lackluster demand. Prices fell dramatically and major global oil producers like Saudi Arabia, and other OPEC producers decided to cut back on production to help stabilize supply and demand, and prices.

U.S. shale producers have not cut back production meanwhile, and there are still concerns over supply dynamics and demand, particularly amid an ongoing trade war between the U.S. and China that has dampened global growth. On Monday, oil prices were trading at $62.22 per barrel for Brent crude and $56.62 for West Texas Intermediate (WTI). Both were comfortably over $100 a barrel around five years ago.

Analysts like Fat Prophets’ David Lennox feel that the IPO could be coming too late; “We think this IPO is probably several years too late. You’ve now got in the U.S. a well-established competitor producing 12 million barrels of oil a day whereas several years ago that wasn’t even around,” Lennox said.

“There’s a lot of questions that we’ll have to sit down and look at,” he added.

https://www.cnbc.com/2019/11/04/4-reasons-why-analysts-are-cautious-of-saudi-aramcos-ipo.html

7.Payroll Numbers Show Economy Still Chugging

Another Solid Month for the Job Market

Posted by lplresearch

Economic Blog

November 1, 2019

The U.S. labor market stood strong against headwinds in October.

Nonfarm payrolls increased 128,000 last month, higher than consensus estimates for an 85,000 gain. October’s payrolls beat expectations despite a 42,000 slide in automaker payrolls, largely from the General Motors strike. August and September’s job gains were also revised up by 95,000.

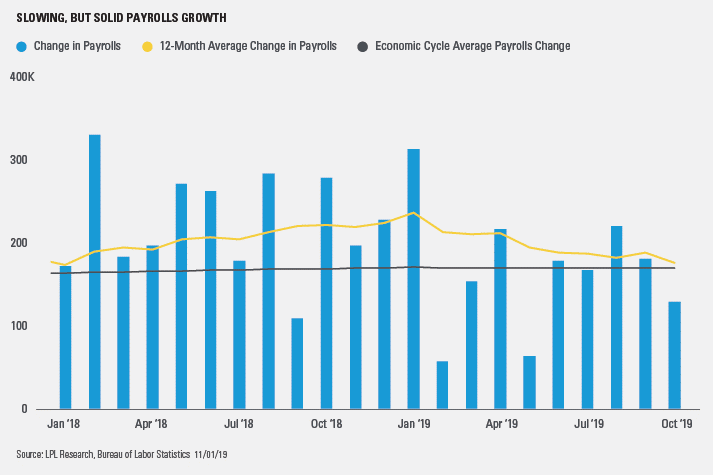

As shown in the LPL Chart of the Day, payrolls have grown an average of 175,000 over the past 12 months, around the average pace for this economic expansion.

Solid October jobs data shows the engine of the U.S. economy is humming along despite elevated global uncertainty, a good sign for future growth as improving hiring conditions fuel consumer spending and confidence. Payrolls growth has moderated this year, but we’ve also expected some slowing in hiring as the cycle ages and the labor market tightens further.

8.Microsoft experimented with a 4-day workweek, and productivity jumped by 40%

Lisa Eadicicco

21 hours ago

Snapchat

Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella. Microsoft

- Microsoft found that implementing a four-day workweek led to a 40% boost in productivity, the company announced as part of the results of its “Work-Life Choice Challenge.”

- The summer project examined work-life balance and its effect on productivity and creativity.

- As part of the experiment, Microsoft’s Japan subsidiary closed every Friday in August, resulting in higher productivity than in August 2018, the company said.

- Visit Business Insider’s homepage for more stories.

An experiment that involved reducing the workweek by one day led to a 40% boost in productivity in a Microsoft subsidiary in Japan, the technology giant announced last week.

The trial was part of Microsoft’s “Work-Life Choice Challenge,” a summer project that examined work-life balance and aimed to help boost creativity and productivity by giving employees more flexible working hours.

Microsoft Japan closed its offices every Friday in August and found that labor productivity increased by 39.9% compared with August 2018, the company said. Full-time employees were given paid leave during the closures.

The company said it also reduced the time spent in meetings by implementing a 30-minute limit and encouraging remote communication.

Microsoft isn’t the first to highlight the productivity benefits of a four-day workweek. Andrew Barnes, the founder of a New Zealand estate-planning firm, Perpetual Garden, said he conducted a similar experiment and found that it benefited both employees and the company, according to CNBC. It has adopted the four-day workweek permanently.

Studies have found there’s demand for a shorter workweek. Last year, in a study of nearly 3,000 workers in eight countries by the Workforce Institute at Kronos and Future Workplace, most said their ideal workweek would be four days or less.

It’s not just the employees who benefited from Microsoft’s four-day-workweek experiment — Microsoft found that it helped preserve electricity and office resources as well. The number of pages printed decreased by 58.7%, while electricity consumption was down by 23.1% compared with August 2018, the company said.

https://www.insider.com/microsoft-4-day-work-week-boosts-productivity-2019-11

9.Blue spaces: why time spent near water is the secret of happiness

Coastal environments have been shown to improve our health, body and mind. So should doctors start issuing nature-based prescriptions?

‘People who visit the coast at least twice weekly tend to experience better general and mental health,’ says Dr Lewis Elliott. Composite: Getty Images

After her mother’s sudden death, Catherine Kelly felt the call of the sea. She was in her 20s and had been working as a geographer in London away from her native Ireland. She spent a year in Dublin with her family, then accepted an academic position on the west coast, near Westport in County Mayo. “I thought: ‘I need to go and get my head cleared in this place, to be blown away by the wind and nature.’”

Kelly bought a little house in a remote area and surfed, swam and walked a three-mile-long beach twice a day. “I guess the five or six years that I spent there on the wild Atlantic coast just healed me, really.”

She didn’t understand why that might be until some years later, when she started to see scientific literature that proved what she had long felt intuitively to be true: that she felt much better by the sea. For the past eight years, Kelly has been based in Brighton, researching “outdoor wellbeing” and the therapeutic effects of nature – particularly of water.

In recent years, stressed-out urbanites have been seeking refuge in green spaces, for which the proven positive impacts on physical and mental health are often cited in arguments for more inner-city parks and accessible woodlands. The benefits of “blue space” – the sea and coastline, but also rivers, lakes, canals, waterfalls, even fountains – are less well publicised, yet the science has been consistent for at least a decade: being by water is good for body and mind.

Proximity to water – especially the sea – is associated with many positive measures of physical and mental wellbeing, from higher levels of vitamin D to better social relations. “Many of the processes are exactly the same as with green space – with some added benefits,” says Dr Mathew White, a senior lecturer at the University of Exeter and an environmental psychologist with BlueHealth, a programme researching the health and wellbeing benefits of blue space across 18 (mostly European) countries.

An extensive 2013 study on happiness in natural environments – to White’s mind, “one of the best ever” – prompted 20,000 smartphone users to record their sense of wellbeing and their immediate environment at random intervals. Marine and coastal margins were found by some distance to be the happiest locations, with responses approximately six points higher than in a continuous urban environment. The researchers equated it to “the difference between attending an exhibition and doing housework”.

The benefits of ‘blue space’ – the sea, but also rivers, lakes, canals, waterfalls, even fountains – are less well publicised than green space. Photograph: tottoto/Getty Images

Although living within 1km (0.6 miles) of the coast – and to a lesser extent, within 5km (3.1 miles) – has been associated with better general and mental health, it seems to be the propensity to visit that is key. “We find people who visit the coast, for example, at least twice weekly tend to experience better general and mental health,” says Dr Lewis Elliott, also of the University of Exeter and BlueHealth. “Some of our research suggests around two hours a week is probably beneficial, across many sectors of society.” Even sea views have been associated with better mental health.

White says there are three established pathways by which the presence of water is positively related to health, wellbeing and happiness. First, there are the beneficial environmental factors typical of aquatic environments, such as less polluted air and more sunlight. Second, people who live by water tend to be more physically active – not just with water sports, but walking and cycling.

Third – and this is where blue space seems to have an edge over other natural environments – water has a psychologically restorative effect. White says spending time in and around aquatic environments has consistently been shown to lead to significantly higher benefits, in inducing positive mood and reducing negative mood and stress, than green space does.

People of all socioeconomic groups go to the coast to spend quality time with friends and family. Dr Sian Rees, a marine scientist at the University of Plymouth, says the coastline is Britain’s “most socially levelling environment”, whereas forests tend to be accessed by high-income earners. “It’s not seen as being elite or a special place, it’s where we just go and have fun.

“By spending time in these environments, you’re getting what we call ‘health by stealth’ – enjoying the outdoors, interacting with the physical environment – and that also has some different health benefits.”

Even a fountain may do. A 2010 study (of which White was lead author) found that images of built environments containing water were generally rated just as positively as those of only green space; researchers suggested that the associated soundscape and the quality of light on water might be enough to have a restorative effect.

Although participants rated large bodies of water higher than other aquatic environments (and “swampy areas” were rated significantly less positively), the study suggested that any water is better than none – presenting opportunities for beneficial blue space to be designed or retrofitted. “You can’t change where the coast is, but when we’re talking about translating the benefits to other types of environments, there is nothing to stop a well-designed urban fountain,” says Elliott.

“People work with what they have,” says Kelly. When she lived in London, she would head for the Thames when she had a spare 10 minutes “and recalibrate”. Then, four times a year, she would go to Brighton “and the benefits would keep me going for the next few months – so I didn’t get into a place of being overwhelmed or stressed, just keeping myself topped up”.

The coast does seem to be especially effective, however. White suggests this is due to the ebb and flow of the tides. He points out that rumination – focusing on negative thoughts about one’s distress – is an established factor in depression. “What we find is that spending time walking on the beach, there’s a transition towards thinking outwards towards the environment, thinking about those patterns – putting your life in perspective, if you like.”

To go to the sea is synonymous with letting go. Photograph: James Galpin/Getty Images

When you are sailing, surfing or swimming, says White, “you’re really in tune with natural forces there – you have to understand the motion of the wind, the movement of the water”. By being forced to concentrate on the qualities of the environment, we access a cognitive state honed over millennia. “We’re kind of getting back in touch with our historical heritage, cognitively.” Water is, quite literally, immersive.

As well as an academic, Kelly is a wellness practitioner who teaches classes in “mindfulness by the sea”. She says the sea has a meditative quality – whether it is crashing or still, or you are in the water or observing from the shore. “You can immerse yourself in it, which you can’t really do with a green space. You’re present in that moment, you’re looking at something with intention, and whether that’s for two minutes or half an hour, it gives you the benefits in that moment.”

In the future, she believes time in blue space will be a mainstream, formalised response. “The mental health crisis isn’t going anywhere,” she says.

Rees says support for the idea of “blue” or “green” prescriptions for individuals is growing. A “surfing for mental health” group in north Devon is one example she gives of how “nature-based interventions” can work.

By working to characterise and quantify benefits, BlueHealth’s cross-disciplinary team hopes to establish how “blue infrastructure” – the coast, rivers, inland lakes – can help tackle major public health challenges such as obesity, physical inactivity and mental health disorders. A 2016 paper – which White co-authored – put the monetary value of the health benefit of engaging with the marine environment at £176m.

Harnessing the power of blue space could also potentially help to alleviate inequality. “One of our recent papers finds that the benefits of coastal living are strongest for people living in the poorest areas,” says Elliott. For that reason, it is crucial to ensure everyone has access. With proximity to water associated with at least a 10% premium in house prices, White is concerned by the exclusivity of seaside urban development. “What will happen is you’ll get this kind of gentrification, where the people who benefit most will get squeezed inland.”

Access provisions under the revised Marine and Coastal Access Act, which is due to be completed next year, will help, says White. But seaside communities are particularly vulnerable, imminently from seasonal fluctuations in income and environmental degradation, and, in the longer term, sea level rise and extreme weather due to climate change.

Rees says that the benefits of marine environments for our wellbeing are tied to the health of those environments, and that conservation efforts need to factor in the “natural capital” of blue space in supporting our wellbeing. Kelly’s work has found a link between a sense of personal connection to the sea and environmentally friendly behaviours; researchers hope that we may be more inclined to protect blue space if the health benefits are proven.

“To go to the sea is synonymous with letting go,” says Kelly. “It could be lying on a beach or somebody handing you a cocktail. For somebody else, it could be a wild, empty coast. But there is this really human sense of: ‘Oh, look, there’s the sea’ – https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2019/nov/03/blue-space-living-near-water-good-secret-of-happinessand the shoulders drop.”

10.Things That Matter: Three Useful Principles for Life

The best life advice is: Be wary of life advice.

Life, observed the writer Amos Oz, evades every formula. If that’s the case (and it is), then so-called guides for life—those lists of rules, owner’s manuals, and how-to books—are bound to be found wanting. In other words, the best life advice is to be wary of life advice.

That being said, those of us who toil in the teaching profession are charged with preparing our students for life. Such preparation requires that we equip them with some useful tools for navigating the terrain. What should those be?

I often begin my introductory classes by talking about three general principles that can, in my judgment, be quite helpful on the journey of learning and living. I speak of ‘principles’ rather than ‘rules’ because rules, by definition, are specific and rigid prescriptions, often imposed from the outside under threat of punishment. Trying to capture, anticipate, and address the infinite complexity of life and its manifestations with specific and rigid rules is unwise. Life advice is more palatable, and useful, when it articulates guiding principles, since principles are broader, more flexible, and tend to take the form of internal convictions rather than external impositions. ‘Finish all the food on your plate’ is a rule. ‘Be mindful of wastefulness’ is a principle. The latter is better life advice. With that in mind, here goes:

1. Knowledge Matters

The assumption that knowledge has value is quite uncontroversial, and fundamental to the work of teaching. Yet the point deserves emphasis, for several reasons. First, American culture is big on opinions. Speech, after all, is free. And free things tend to get used much, often wastefully. Many of my students are told throughout their early years that they always have a right to an opinion, that their opinions matter a lot, and that all opinions are created equal. This of course is untrue. Indeed, everyone is entitled to their opinions, yet that does not mean that all opinions matter, or that they matter equally. To wit: I have an opinion about how Amazon should be run. So does Jeff Bezos. His opinion matters more. In a well-run life (be it individual or social), a knowledgeable opinion matters more than an ignorant one.

Second, American society is also big on feelings. Many of my young students are taught that how they feel is of prime importance in terms of discerning what’s going on and how they should respond. This is problematic. Now granted, feelings are important. Our emotions provide useful information in our effort to navigate the world. Everyone is entitled to feel what they feel, and there’s often benefit in reflecting on and communicating our feelings honestly. At the same time, feelings are mind events, not world events. The fact that you feel scared does not necessarily mean you are in danger. Recognizing the difference is important, and will require knowledge of the situation, not merely an awareness of your feelings. The fact that you hurt does not necessarily mean that you’ve been wronged. The fact that you feel good does not necessarily mean you are doing good. If you feel like a great driver, you have a feeling, not necessarily driving skill. In a well-run life, your driving skill–that is, your actual knowledge–is more important than your feeling. Knowledge matters.

Of course, this principle is violated often—as when people who have acquired power, wealth, or fame in one area get a pass on spouting ignorant nonsense about another (a phenomenon known as the ‘halo effect’). This seems to have become more common in recent years, as the current cultural conversation appears to devalue knowledge in favor of other currencies that photograph better, such as celebrity, wealth, outrageous opinions, and outraging feelings. Yet violating the principle comes at a cost. A process that devalues expertise begets inferior quality product. Failing to gather—or ignoring—the evidence begets error and injustice.

Another reason why knowledge matters is because what you know defines the parameters of your world. Thought experiment: You come home from work to find your wife in bed with your brother. Now, this is a situation in which you’ve just acquired a new bit of knowledge. At this point, you face some choices; you have many ways in which to react to these new data–you may storm out, start a fight, faint, or join in on the fun. Whatever. It’s a free country. Yet one thing you cannot do is go back to being who you were before that moment. The knowledge has changed you; it has changed your understanding of yourself, and of your wife, and of your brother, and of relationships, and of the world. And the change is irreversible. You may mend things with both your brother and your wife, but you cannot un-see what you saw. You cannot un-know what you know. Even if you recover completely and become whole again, you are not whole in the same way you were before. This is why, as hinted well in the biblical story of Adam and Eve, knowledge is dangerous. It is consequential. It matters.

article continues after advertisement

2. Context Matters

This is perhaps the most important and most often overlooked guiding principle for sound thinking and judgment: Nothing has meaning independent of context. Human affairs in particular cannot be meaningfully reduced to the study (or description) of the individual alone. Granted, we may speak of an object sans context heuristically, in the abstract, for the didactic purposes of simplification or illustration. But to arrive at a practical understanding that can inform successful movement in the world, speaking of anything sans context is unhelpful. For example, pregnancy happens inside the womb. But the womb is nested inside a body that contains a brain–that is to say, a person. And the person is involved in certain specific relationships, in a certain community, inside a culture, at a certain historical time. You can’t understand the meaning and implications of pregnancy without knowing something about all of those layers.

As the above example shows, a complicating factor here is that human phenomena exist within multiple contexts at once. Which of those we choose to emphasize will matter to our understanding. Three types of context that tend to matter greatly to our understanding of human events are the sociocultural, historical, and situational contexts. The sociocultural context refers to the cultural traditions, social expectations, and group processes in which one’s individual life is embedded. Similar gestures, words, or decisions have different meanings in different cultures. Two adult males walking hand in hand means very different things depending on whether it happens in Uganda (where it signals male friendship) or the US (where it signals homosexuality).

Moreover, just as public behavior is given meaning by the culture, so does private, individual behavior. There is no ‘I’ in ‘Alone.’ But there is ‘I’ in ‘Tribe.’ This is to say that selves are built out of cultural materials, using cultural tools. Sociocultural influences are internalized in the socialization process and become parts of our integrated sense of self. The very concepts you use to define yourself—or, for that matter, your very idea of self—have been provided to you by society. Take language, for example. Your culture gave you the gift of language, and now, you consider that language your own. In other words, you have internalized and integrated culture.

This is why even your most private intimate moments carry a cultural stamp. For example, when you make love to your partner in the privacy of your bedroom, your society is right there with you. After all, your understanding of what lovemaking means and how to go about it were taught to you by your culture. Everything about your love making session: the expectations you and your lover have of each other, the scripted dance of dating and mating that brought you here, the things you have come to consider attractive, acceptable, or necessary for arousal, the sex toys and contraceptives you use—these are not of you. They were gifted to you by the sociocultural milieu. Context matters.

article continues after advertisement

Another type of context is historical. Clearly, similar behaviors have different meanings at different historical times. Ideas that were once taken for granted truths are now considered folly. And vice versa. The wealthiest, most powerful person in the world five hundred years ago did not have access to the technology our poorest citizens take for granted today. This is one reason why evaluating the past in terms of the present devolves quickly into meaninglessness. Our ancestors look like backward barbarians to us. But they did not think of themselves as such, and were not such compared to their ancestors. People 500 years from now will look at us as backward barbarians.

Judging human phenomena without regard to the times in which it took place is seductive since hindsight is 20/20, and comparisons to the past often reflect well on the present. But such comparisons often muddy our analysis. To wit: I’m quite certain that Bill Gates abhors the idea of slavery. Thomas Jefferson, on the other hand, embraced it. That does not mean that Gates is good and that Jefferson was evil. Both of them are, in fact, normative in the context of their historical time and particular culture. Thus, they are more alike than different. In other words, if Gates lived in Jefferson’s time he’d be a slave master, too. Person-(or event or object)-in-context is the lowest meaningful unit of analysis. Thus, it is fairer to compare our ancestors in their context to us in ours.

The third important context is situational. Clearly, different situations call for different behaviors. And the same behavior acquires different meanings depending on the situational context in which it is emitted. Indeed, one of the ways we judge mental health and illness is by noting a mismatch between behavior and situation, as when someone laughs at the funeral, or takes his pants off in public.

article continues after advertisement

Even the meaning of things we assume to be absolute, universal, or self-evident are in fact tethered to situational context. Telling the truth, for example, is broadly seen as a good thing. Yet in some contexts—for example, if you’re hiding Jews in your basement in Europe during WWII, and the SS soldiers are at your door asking you if you’re hiding any Jews—truth-telling would be immoral. This is why we say that in psychology, the correct answer to most every question is ‘it depends.’ On what? On context.

3. Things Are Not What They Seem

This idea is neither new nor original. An essence of humanity is embodied in our tendency to want to look under the hood or to peek behind the curtain; our curiosity about how, and to what ends, the myriad appearances around us are produced. Many grand historical ideas involve upending the obvious:

Freud’s notion of the unconscious is one example. Per Freud, the true meaning of the things we do is hidden from others and also from ourselves. The woman doting incessantly over her baby is motivated not by love, but by resentment.

Darwin’s great insight involved the realization that nature, which many Victorians saw as beautiful, harmonious and graceful in its various manifestations—is actually a brutal, ceaseless war for survival.

Marx’s grand theory was premised on the notion that capitalism, the seemingly wining economic system, was in fact doomed by its very own structure, as the proletariat, upon whose labor the wealth of the bourgeoisie depends, were bound to eventually revolt against their exploiters.

And so on.

The reason that things are not what they seem has to do with the structure of our evolved brain. We all must rely on our senses when taking in the world. We have no other means by which to commerce with the ‘there’ that’s out there. Our senses are systems. All systems have boundaries, that is to say limitations, that is to say, certain things they cannot do (for example, we can’t breathe underwater). All systems also have a character, that is to say specifications, that is to say certain things they do better than other things they do (for example, we see better in daylight than at night).

Evolution has shaped our senses to include certain useful tendencies. We learn certain tasks (e.g.: to fear a snake) more easily than others (to fear a table). We are drawn to and prefer certain things over others (babies track a moving object at birth; they prefer symmetry, and the smell of vanilla over ammonia). These sensory adaptations serve a survival purpose, but they are in essence biases, and thus, by definition, distortive.

Moreover, it is by now common knowledge that our senses do not passively transmit, record, and store information from the outside world but rather actively participate in shaping the form and meaning of these data. We act on the world as it acts upon us.

Your memory, thus, is not a recording of your life events, even though it seems so. Rather, it is a story constructed about those events in retrospect. You don’t remember all of what happened to you. You remember a version you’ve constructed. That version omits certain parts, emphasizes others, and makes up some others for good measure. In other words, what you remember will depend not just on what actually happened, but also on factors such as your mood at the time of the event, your level of arousal at the time, your mood at the time of recall, and on how you are asked to remember, when, by whom, and how often.

Another aspect of this principle refers to the role of expectations. Everyone has heard that seeing is believing. And this is in part true. Humans rely on vision to a great extent, and so we use this sense to verify things for ourselves. Fewer people though realize that the opposite of this equation is also true: Believing is seeing. That is to say, what you expect to see, hope to see, and believe you will see, you tend to see, independently of what’s actually there. People who believe in God see his good works everywhere. People who don’t fail to find him anywhere.

Thought experiment: Imagine two equally matched teams. One anticipates a loss. The other believes it is going to win. At some point in the game, either team may fall behind. Yet the team that expects to lose will see that as prophecy fulfilled, an inevitability, a signal, while the team that expects to win will see falling behind as a temporary setback, an error, random noise. Now, which team is more likely to win? The one that expected to. This result will seem right to both teams. But it isn’t, insomuch as it reflects not their true (evenly matched) abilities, but their (distorted) expectations.

In sum, while neither comprehensive nor exhaustive, the three principles described above are useful to consider as one labors to survive intact the typhoon of existence. How may these principles be translated into action? Well, knowledge matters, so try to learn something. Context matters, so in beholding things, consider too the environment in which they’re embedded. And things are not what they seem, so don’t trust your vision blindly. Examine things again