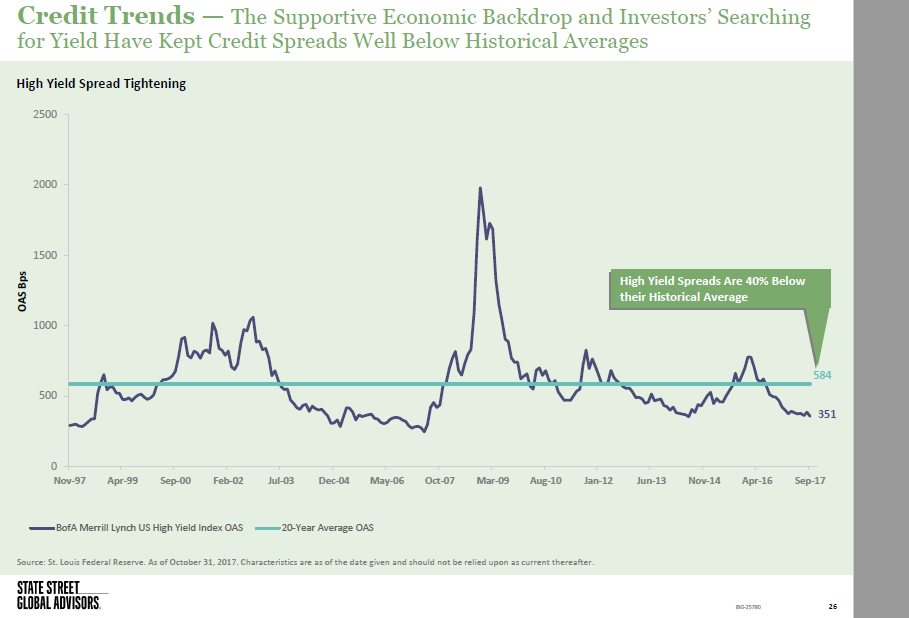

1.Follow Up to Last Week’s Gundlach Comments…High Yield Spreads are 40% Below Their Historical Averages.

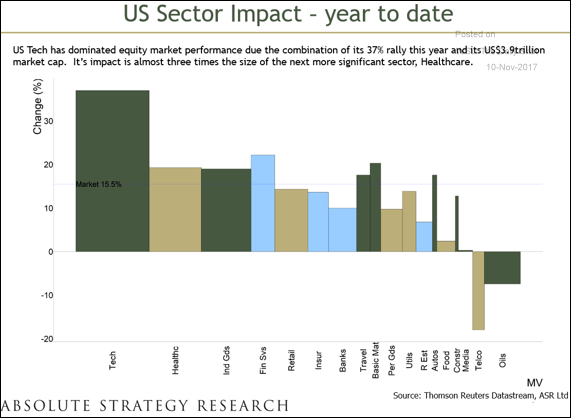

2.Tech Sector’s Massive Contribution to Performance this Year.

Equity Markets: Here is how each sector contributed to the US market’s performance this year (combining each sectors’ returns and weights).

Source: Absolute Strategy Research

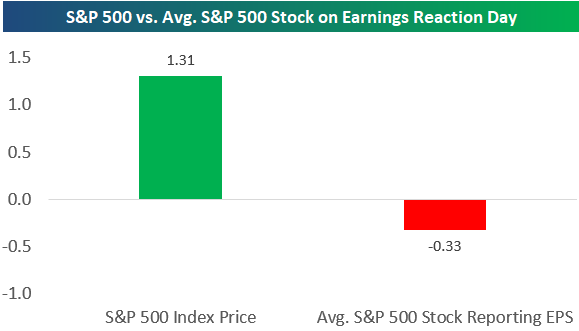

3.Follow Up from Last Week…Another Look at Muted Reaction from Earnings Season after 2300 Companies Reported.

Underlying Earnings Season Weakness

Nov 10, 2017

More than 2,300 companies have now reported their Q3 2017 earnings results since earnings season began back on October 9th. With just a week left until the unofficial end of the reporting period, the S&P 500 is up 1.3% since the start of earnings season. While the S&P’s gain is nice to see, the underlying price action of S&P 500 stocks that have reported has been weak. This is a concerning sign. As shown in the chart below, the average S&P 500 stock that has reported EPS this season has fallen 0.33% on its earnings reaction day. This means investors have been doing more selling than buying of individual stocks that make up the S&P 500 in reaction to their earnings news.

https://www.bespokepremium.com/think-big-blog/

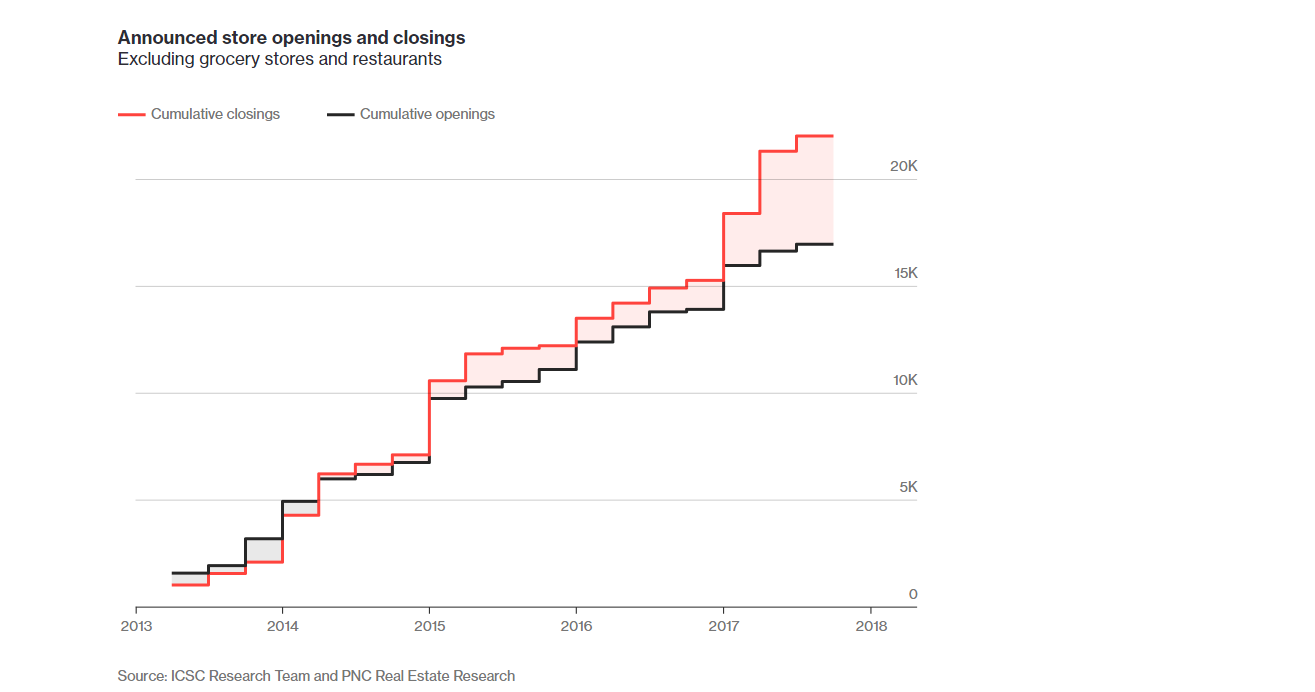

4.American Retailers have a Problem Bigger than Amazon…Debt.

America’s ‘Retail Apocalypse’ Is Really Just Beginning

By Matt Townsend, Jenny Surane, Emma Orr and Christopher Cannon

November 8, 2017

The so-called retail apocalypse has become so ingrained in the U.S. that it now has the distinction of its own Wikipedia entry.

The industry’s response to that kind of doomsday description has included blaming the media for hyping the troubles of a few well-known chains as proof of a systemic meltdown. There is some truth to that. In the U.S., retailers announced more than 3,000 store openings in the first three quarters of this year.

The reason isn’t as simple as Amazon.com Inc. taking market share or twenty-somethings spending more on experiences than things. The root cause is that many of these long-standing chains are overloaded with debt—often from leveraged buyouts led by private equity firms. There are billions in borrowings on the balance sheets of troubled retailers, and sustaining that load is only going to become harder—even for healthy chains.

The debt coming due, along with America’s over-stored suburbs and the continued gains of online shopping, has all the makings of a disaster. The spillover will likely flow far and wide across the U.S. economy. There will be displaced low-income workers, shrinking local tax bases and investor losses on stocks, bonds and real estate. If today is considered a retail apocalypse, then what’s coming next could truly be scary.

Until this year, struggling retailers have largely been able to avoid bankruptcy by refinancing to buy more time. But the market has shifted, with the negative view on retail pushing investors to reconsider lending to them. Toys “R” Us Inc. served as an early sign of what might lie ahead. It surprised investors in September by filing for bankruptcy—the third-largest retail bankruptcy in U.S. history—after struggling to refinance just $400 million of its $5 billion in debt. And its results were mostly stable, with profitability increasing amid a small drop in sales.

Making matters more difficult is the explosive amount of risky debt owed by retail coming due over the next five years. Several companies are like teen-jewelry chain Claire’s Stores Inc., a 2007 leveraged buyout owned by private-equity firm Apollo Global Management LLC, which has $2 billion in borrowings starting to mature in 2019 and still has 1,600 stores in North America.

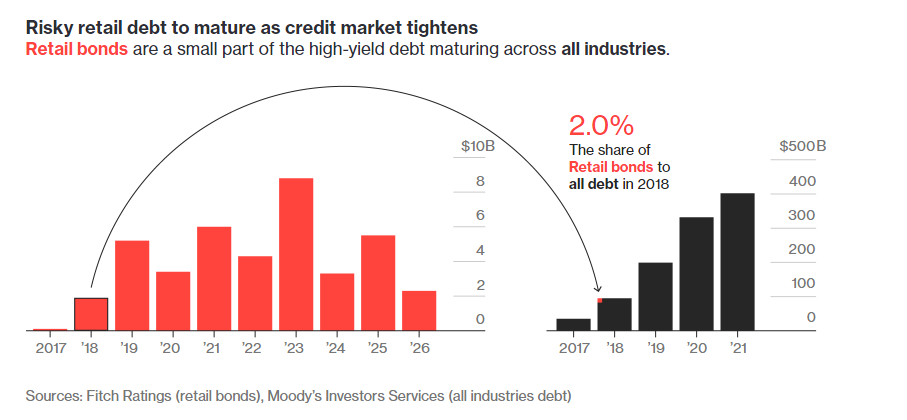

Just $100 million of high-yield retail borrowings were set to mature this year, but that will increase to $1.9 billion in 2018, according to Fitch Ratings Inc. And from 2019 to 2025, it will balloon to an annual average of almost $5 billion. The amount of retail debt considered risky is also rising. Over the past year, high-yield bonds outstanding gained 20 percent, to $35 billion, and the industry’s leveraged loans are up 15 percent, to $152 billion, according to Bloomberg data.

Even worse, this will hit as a record $1 trillion in high-yield debt for all industries comes due over the next five years, according to Moody’s. The surge in demand for refinancing is also likely to come just as credit markets tighten and become much less accommodating to distressed borrowers.

One testament to that negativity on retail came earlier this year, when Nordstrom Inc.’s founding family tried to take the department-store chain private. They eventually gave up because lenders were asking for 13 percent interest, about twice the typical rate for retailers.

https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2017-retail-debt/

5.Meanwhile Americans Trust Amazon More than Their Bank.

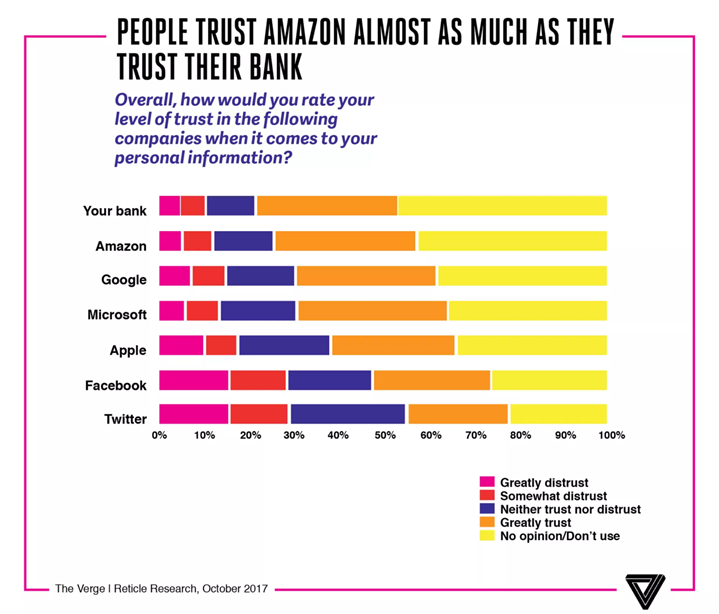

These surveys, via The Verge, are fascinating:

“Respondents trusted Facebook less than Google, and “trust” was a primary factor for individuals who abstained from using Facebook overall. Respondents trusted Amazon almost as much as their own bank. Of all the companies named in our survey, respondents were most likely to recommend services from Amazon to their family and friends. Twitter sits on the opposite side of the spectrum: a quarter of respondents said they are probably, or not at all likely, to recommend the service.”

People Trust Amazon Almost As Much As They Trust Their Bank

Source: The Verge

6.Fund Flows into Emerging Markets $70B this Year vs. $114B Outflows the Last 4 Years.

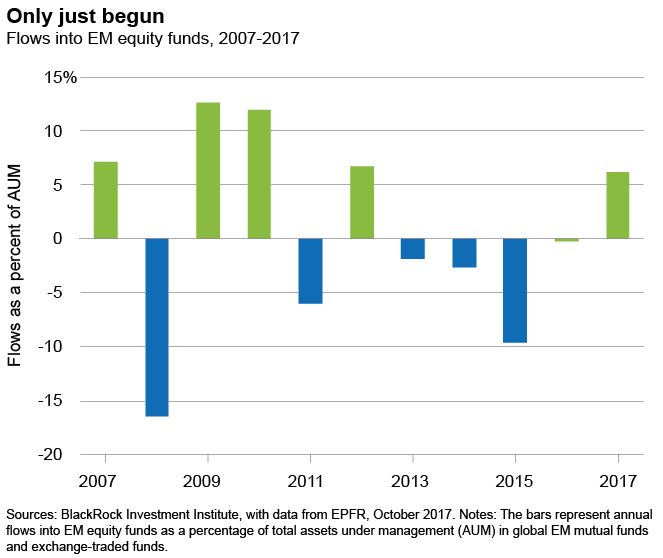

Net flows into EM equity funds are on track to reach $70 billion this year, or about 6% of assets under management (AUM), as illustrated in the chart below. This is a solid reversal from the $114 billion in outflows over the last four years (amounting to 14% of AUM). And yet fund flows and price momentum are not signaling mania, research from BlackRock’s Risk and Quantitative Analysis team shows.

Blackrock Blog.

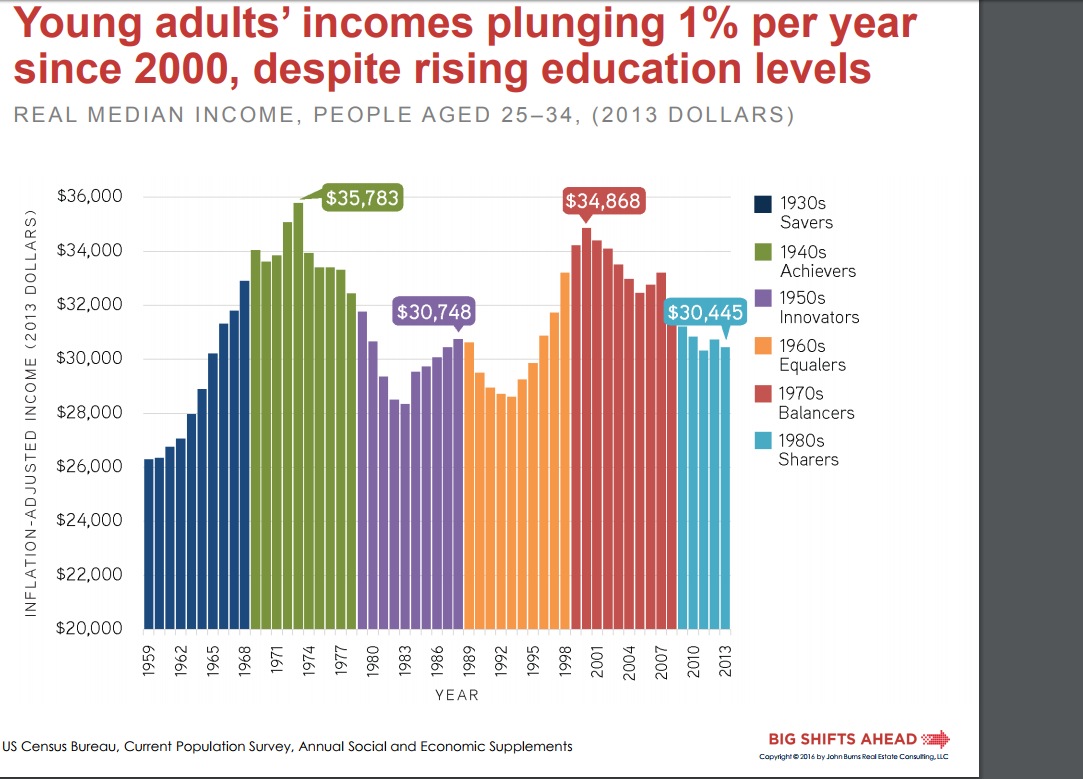

7.Wage Growth Still Stagnant …Lack of Inflation in Wages.

file:///C:/Users/mtopley/Downloads/BigShiftsAhead_Burns-Porter%20(1).pdf

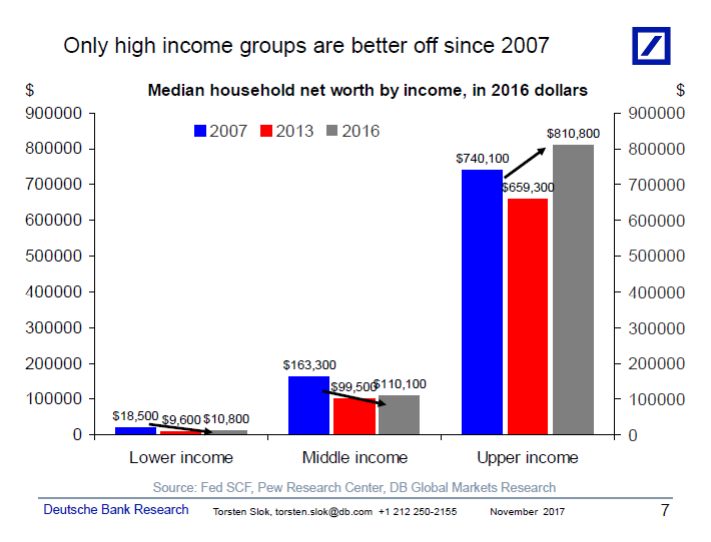

8.Since 2007 median household net worth has increased for upper income households and declined for lower and middle income households, see chart below.

Torsten Sløk, Ph.D.

Chief International Economist

Managing Director

Deutsche Bank Securities

60 Wall Street

New York, New York 10005

Tel: 212 250 2155

9.Read of the Day….Next Economic Driver Housing Market???

Millennials Leave the Basement to Buy Homes: Barry Ritholtz

2017-11-10 16:41:11.356 GMT

By Barry Ritholtz

(Bloomberg View) — A few years ago, I wrote “The economy

will one day improve, and the millennials will move out of their

parents’ basements. When that happens, expect to see

homeownership rates move back higher.”

That day has arrived. Millennials are forming new

households, moving to the suburbs, buying furnishings and SUVs.

According to Zillow Group data, people aged 18 to 34 have become

the largest group of homebuyers in the U.S.

This wasn’t the case just a few years ago, when the Pew

Research Center did an analysis of U.S. Census Bureau data. It

found that in 2012, “36% of the nation’s young adults ages 18 to

31 were living in their parents’ home. This is the highest share

in at least four decades.”

The reversal of this phenomenon is an important contributor

to the momentum behind the economic recovery from the credit

crisis; it also is potentially significant for the next leg up

in U.S. equity markets.

Have a look at the chart below showing homeownership rates.

It shows that the percentage of Americans who owned their own

homes peaked in 2004. That was, not surprisingly, about the high

point of the credit bubble.

Before the financial crisis, the basis for credit and

lending was the borrower’s ability to service the loan. Job

history, credit score, income and other debt all figured into

any lending decision, especially for mortgages. From 2002 to

2007, the basis of that credit decision shifted to the lenders’

ability to sell the mortgage to a third-party securitizer. That

is why so many nonbank lenders were offering loans without the

standard documentation, sometimes referred to as no-doc or liar

loans. My favorite description of these buyers was “renters with

an option to default” — and as we saw in the financial crisis,

millions of them were unable to repay their loans.

Amid a flood of easy credit, home sales peaked in volume in

2005 and prices in 2006. Once the crisis hit, foreclosures

soared and prices fell 30 percent or more nationwide, though

some areas such as South Florida, California, Nevada and Arizona

fared much worse. This ultimately led to broad tightening of

lending standards, along with doubts about the value of owning a

home and a decade-long decline in ownership rates.

We have now seen that pattern reverse during the past year

or so. Homeownership bottomed in mid-2016, and has gained a full

percentage point since then. If this were a stock, you would say

the trend has been broken.

Several forces play a part here:

No. 1 Rising rents: As they go higher, the calculus of

buying versus renting tilts more toward ownership than being a

tenant

No. 2 Strengthening economy: Increasing job creation and

faster wage growth makes ownership and the attendant mortgage-

interest tax deduction more attractive

No. 3 Household formation: The decline that followed the

credit crisis is ending and millennials are vacating their

parents’ basements, moving in together, getting married. The

next step, along with having children, often is buying a home;

No. 4 Passage of time: As the credit crisis recedes from

memory, fear of making large financial commitments is in

decline.

People like to debate why residential real estate has a

special place in the U.S. tax code. There are two main reasons:

ownership brings with it obligations, including commitment to

neighborhoods, local schools and good municipal government. The

other is that owners stimulate the economy more than renters.

While we can debate exactly how true the first point is,

there is no debate about the second: Owners tend to improve

their properties — they buy more furniture and appliances; put

in new kitchens and bathrooms; own more cars; spend more on

landscaping. This consumption results in higher revenue and

profits for corporations, and it eventually works its way into

higher stock prices.

All of this should figure in any debate about reducing or

eliminating the mortgage deduction. Although there may be some

sound grounds for cutting or ending this tax break, it should be

balanced against the harm its elimination might do as an

incentive for homeownership. The housing market is still

recovering. Let’s hope no one does anything foolish at this time

to disrupt it.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the

editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Household formation –people living together or getting married

— tends to precede home purchases. For this reason, I find it

worthwhile to follow Federal Reserve (and other) research on

household formation such as this, this, this, and this.

Some people, including Jed Kolko, chief economist and vice

president for analytics at Trulia find fault with this metric. I

don’t.

To contact the author of this story:

Barry Ritholtz at britholtz3@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story:

James Greiff at jgreiff@bloomberg.net

10.20 Years Ago, Jeff Bezos Said This 1 Thing Separates People Who Achieve Lasting Success From Those Who Don’t

Amazon founder Jeff Bezos has stuck to this simple yet powerful approach, and it’s one all of us can take.

Jeff Bezos founded Amazon in 1994. Twenty-three years later, he’s one of the richest people in the world. But while Amazon is undeniably a tech company, the business was built on this old-school premise:

Focus on the things that don’t change.

The premise, while simple, is also easy to forget when innovation seems to be the secret of massive success. Catching the next wave, predicting the next trend, disrupting an industry, or hacking your way to near-immediate success, sparking change … that’s what works.

But it’s hard to be innovative. It’s hard to be truly disruptive. Shortcuts typically yield short-term benefits. Knowing what will change — that’s incredibly difficult.

Bezos doesn’t worry about what will change. He focuses on what won’t change. Bezos built Amazon around things he knew would be stable over time, investing heavily in ensuring that Amazon would provide those things — and improve its delivery of those things.

Here’s Bezos:

I very frequently get the question: “What’s going to change in the next 10 years?” And that is a very interesting question; it’s a very common one. I almost never get the question: “What’s not going to change in the next 10 years?” And I submit to you that that second question is actually the more important of the two — because you can build a business strategy around the things that are stable in time. … [I]n our retail business, we know that customers want low prices, and I know that’s going to be true 10 years from now. They want fast delivery; they want vast selection.

It’s impossible to imagine a future 10 years from now where a customer comes up and says, “Jeff, I love Amazon; I just wish the prices were a little higher.” “I love Amazon; I just wish you’d deliver a little more slowly.” Impossible.

And so the effort we put into those things, spinning those things up, we know the energy we put into it today will still be paying off dividends for our customers 10 years from now. When you have something that you know is true, even over the long term, you can afford to put a lot of energy into it.

Twenty years ago, Bezos said the same thing. In his 1997 shareholder letter, he wrote:

We believe that a fundamental measure of our success will be the shareholder value we create over the long term … Because of our emphasis on the long term, we may make decisions and weigh tradeoffs differently than some companies.

Focusing on things that won’t change does not guarantee success — but it provides as close a foundation for success as you will find.

That’s true even if you don’t start a company; here are a few timeless principles that consistently provide professional and personal success.

Focus on collecting knowledge …

Competing is a fact of professional life: with other businesses, other products, other people. It’s not a zero-sum game, but it is a game we all try to win.

Smart people win a lot.

Smarter people win even more often.

Continually striving to gain more experience and more knowledge is the second-best way to succeed.

… But always focus more on collecting knowledgeable people.

You can’t know everything. But you can know enough smart people that together you know almost everything.

And, together, do almost anything.

Work hard on getting smarter. Work harder on getting smart people on your side.

How?

Always give before receiving.

The goal of networking is to connect with people who can provide a referral, help make a sale, share important information, serve as a mentor, etc. When we network, we want something.

But, especially at first, never ask for what you want. Forget about what you want and focus on what you can give.

Giving is the only way to establish a real relationship and a lasting connection. Focus solely on what you can get out of the connection and you will never make meaningful, mutually beneficial connections.

Approach networking as if it’s all about them and not about you and you’ll build a network that approaches it the same way.

And you’ll create more than contacts. You’ll make friends.

Always look past the messenger and focus on the message.

When people speak from a position of position of power or authority or fame, it’s tempting to place greater emphasis on their input, advice, and ideas.

Warren Buffett? Yep, gotta listen to him. Sheryl Sandberg? Yes. Richard Branson? Absolutely.

That approach works to a point — but only to a point. Really smart people strip away all the framing that comes with the source — both positive and negative–and evaluate information, advice, or input solely on its merits.

When Branson says, “Screw it; just do it and get on with it,” it’s powerful.

If the guy who delivers your lunch says it, it should be just as powerful.

Never discount the message because you discount the messenger. Good advice is good advice–regardless of the source.

Always work on “next.”

It’s impossible to predict what will work, much less how well it will work. Some products stick — for a while. Some services flourish — and then don’t. Some ventures take off — and flame out. Some careers take off — and then stagnate.

You will always need a “next”: a new product, a new service, a new customer or connection.

No matter how successful you are today, always have a next in your pipeline. If somehow your current products or services or ventures continue to thrive, great: You will have created a bigger line of products and services and ventures. If your career trajectory continues to climb, great: You will still have added new connections, new skills, and new perspectives that will only add to your value.

(The same applies to career pursuits or even personal pursuits; as I describe in my upcoming book, The Motivation Myth, we should all be an “and.” We don’t all need to be serial entrepreneurs, but we should all be serial achievers.)

That’s how successful people weather the storm when times are tough, and become even more successful when business is booming.

Always take responsibility.

If you’re always right, you never grow. One of the best things you can do is to be wrong, because when you make a mistake you are given the chance to learn.

(Don’t worry. Every successful person has failed numerous times. Most have failed more than you. That’s why they’re successful today.)

Own every mistake, every miscue, and every failure. Say you made a mistake. Say you messed up. Say it to other people, but more important, look in the mirror and say it to yourself.

Then commit to making sure that next time things will turn out very differently.

Always turn ideas into actions.

The word idea should be a verb, not a noun, because no idea is real until you turn that inspiration into action.

Ideas without action aren’t ideas. They’re regrets.

Every day we let hesitation and uncertainty stop us from acting on our ideas. Fear of the unknown and fear of failure are what stop me, and may be what stops you, too.

Think about a few of the ideas you’ve had, whether for a new business, a new career, or even just a part-time job. Looking back, many of your ideas would have turned out well, especially if you had given them your best effort.

Trust your analysis, your judgment, and your instincts. Trust them more than you do. Trust your willingness to work through challenges and roadblocks.

Granted, you won’t get it right all the time, but when you let an idea stay an idea, you almost always get it wrong.