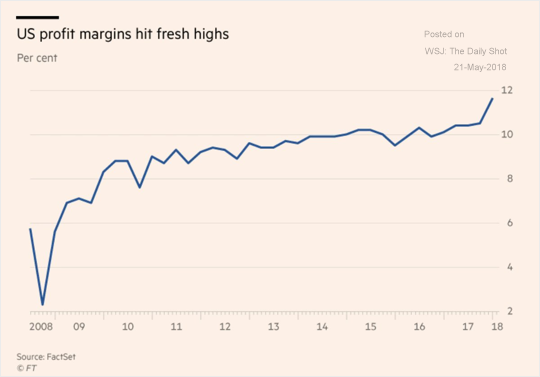

1.U.S. Profit Margins at Record Highs.

Equity Markets: US profit margins are at record highs.

Source: @trevornoren; Read full article

https://blogs.wsj.com/dailyshot/

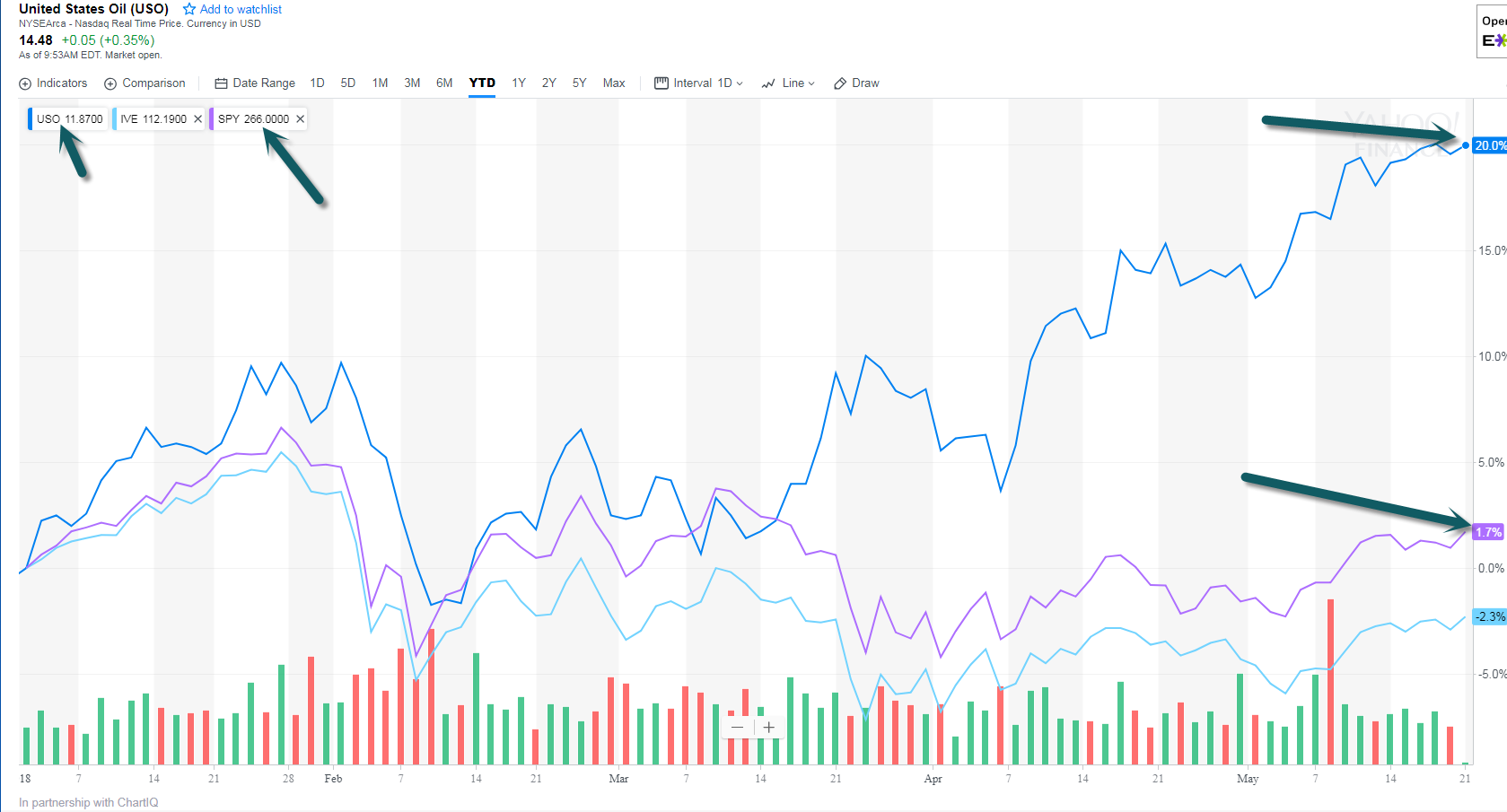

2.USO Oil ETF +20% YTD.

Oil and Gas ETFs YTD

From Nasdaq Dorsey Wright

http://business.nasdaq.com/intel/dorsey-wright/index.html

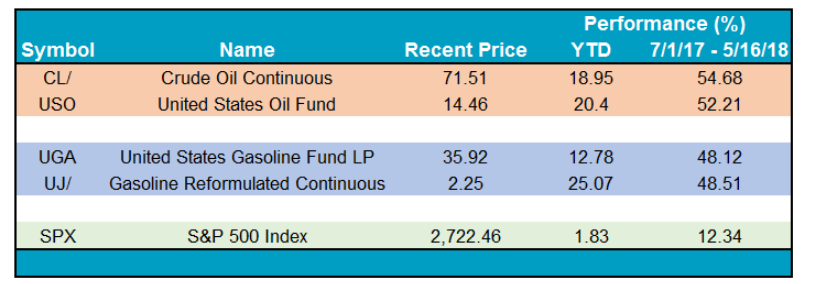

3.Components of “at the pump” Gasoline Prices

http://business.nasdaq.com/intel/dorsey-wright/index.html

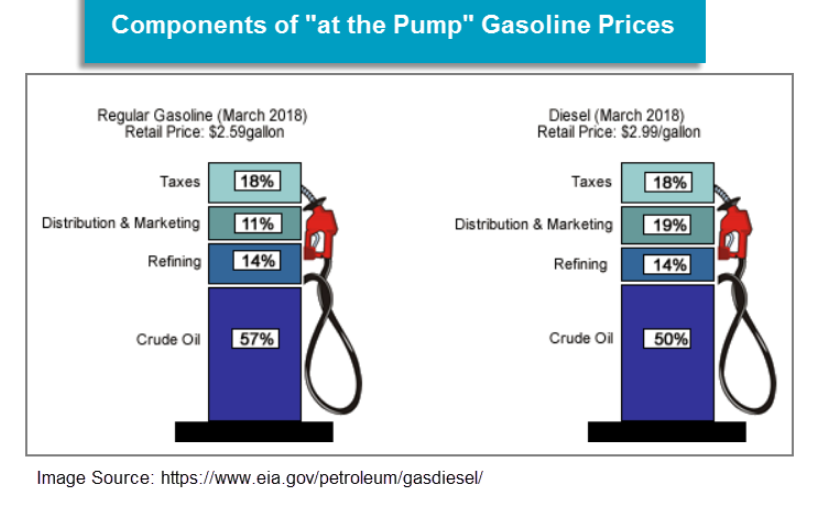

4.Corporate Bonds Off to Worst Start in 20 Years.

The US corporate debt market is having one of its worst starts to a year since the 1990s

- A major sell-off is underway in the US corporate debt market.

- US corporate debt is suffering one of its worst sell-offs in 18 years, according to JPMorgan research.

- The widely watched ICE Bank of America Merrill Lynch corporate debt indices shows that investors in investment grade US company debt have lost close to 4% this year.

Fears of excessive valuations are pushing investors away from US corporate debt.

As such, US corporate debt is suffering one of its worst sell-offs in 18 years, according to JPMorgan research cited by Bloomberg,which shows that US corporate bonds just posted “their third-worst 100-day returns since 2000.”

Separately, t he Financial Times reports that “high-quality US corporate bonds had their worst start to a year in at least two decades.”

The continuing normalisation of interest rates around the globe is helping to drive the bond sell-off. This is particularly true in the US, where the Federal Reserve has increased its base six times since the end of 2015. The main Fed Funds rate is now between 1.5% and 1.75%, the highest rate since the financial crisis.

http://www.businessinsider.com/us-corporate-debt-sell-off-gains-pace-2018-5

LQD Corporate Debt ETF—50day thru 200 day to downside…200day sloping downward.

5.Earnings Season Wrap….68% of Stocks Beat Earnings

Investors Liked What They Saw During Earnings Season

May 21, 2018

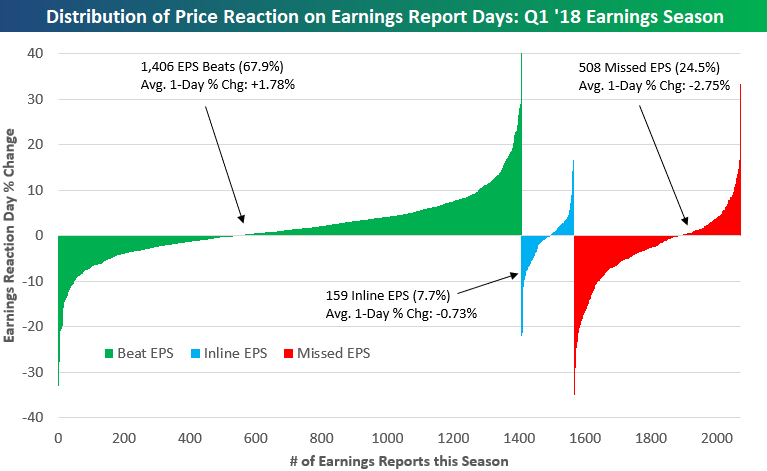

Roughly 2,100 companies reported earnings during the unofficial Q1 2018 reporting period that ran from April 9th through May 18th. We track the one-day stock price performance of every company that reports earnings. This obviously helps us monitor individual stock performance, but it also gives us an idea of how investors are reacting to earnings results at the macro level. (In order to track performance, remember that for a stock that reports earnings in the morning before the open of trading, we use its price change on that trading day. For a stock that reports earnings after the close of trading, we use its price change on the next trading day.)

Below is a chart that shows the one-day price reaction (%) for every stock that reported earnings during the Q1 reporting period. We’ve separated the distribution by stocks that beat EPS estimates, missed EPS estimates, and reported inline EPS estimates. As shown, 67.9% of stocks beat EPS estimates, while 24.5% missed and 7.7% reported inline. The average stock that beat EPS estimates gained 1.78% on its earnings reaction day. The average stock that missed EPS estimates had a one-day drop of 2.75% in response, while the average inline report saw a one-day price drop of 0.73%.

While the average stock that beat EPS estimates gained 1.78% on its earnings reaction day, you can see in the chart that there were hundreds of stocks that beat but still fell in price. Similarly, while most stocks that missed EPS estimates fell on the news, there were plenty that gained as well.

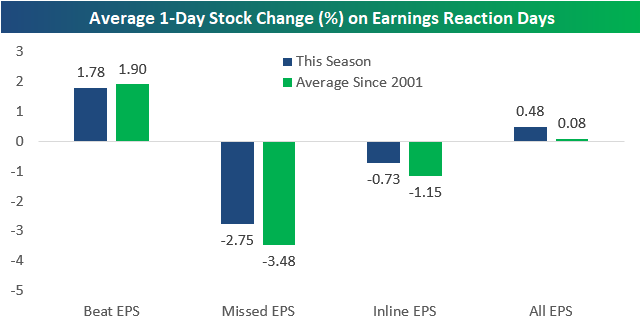

The chart below uses data pulled directly from our Earnings Screener. It shows the average one-day stock price reaction to various earnings outcomes during the Q1 2018 reporting period compared to all periods since 2001. As shown, the average stock that beat EPS estimates this season gained 1.78% on its earnings reaction day. Since 2001, the average stock that has beaten EPS estimates has gained 1.90% on its earnings reaction day. So this season, earnings beats gained slightly less than normal.

For stocks that missed EPS estimates, this season they fell an average of 2.75% on their earnings reaction days. Since 2001, stocks that have missed EPS estimates have averaged a one-day decline of 3.48%. So this season, stocks that missed EPS estimates fell much less than they usually do. Stocks that reported inline EPS fell a lot less than they normally do as well. Combining the beat, miss, and inline outcomes, the average one-day change for all stocks that reported this season was +0.48%. Since 2001, the average one-day change for all stocks that have reported earnings has been +0.08%. That means that this season, stocks reacted much more positively than usual, and the reason was because the inline and missed reports fell less than they usually do.

https://www.bespokepremium.com/think-big-blog/

6.TAN Solar ETF +41% One Year

TAN Solar ETF

Solar: World’s Fastest-Growing Power Source

This week, it was announced California would require solar panels on all new home construction in the state starting in 2020. (Some municipalities, like San Francisco and South Miami, Florida, already have such requirements in place.)

This will drive up home prices and cut into homebuilders’ bottom lines, to be sure. But it’s also a welcome boost for the solar industry, which has faced several head winds so far in the Trump era, from international trade wars that have levied 30% tariffs on Chinese-made solar components to the president pulling the country out of the Paris Climate Agreement.

It’s no secret the Trump administration loves fossil fuels. But it’s too late to turn back the clock on solar, as the sector is booming, both at home and abroad. Solar is already the fastest-growing power source in the world—probably because, in many instances, it’s also cheaper than fossil fuels.

It’s also a significant economic driver: More Americans are employed by the solar industrythan the oil, gas and coal industries combined. That’s nothing compared to China, however, which has nine times as many solar power jobs; you can even see their solar buildout from space.

With the fifth-largest economy in the world throwing its weight behind solar, it’s clear that bright times (sorry) lie ahead for the space. And that’s going to mean good things for the solar industry ETF.

http://www.etf.com/sections/features-and-news/etf-week-guggenheim-solar-etf-tan

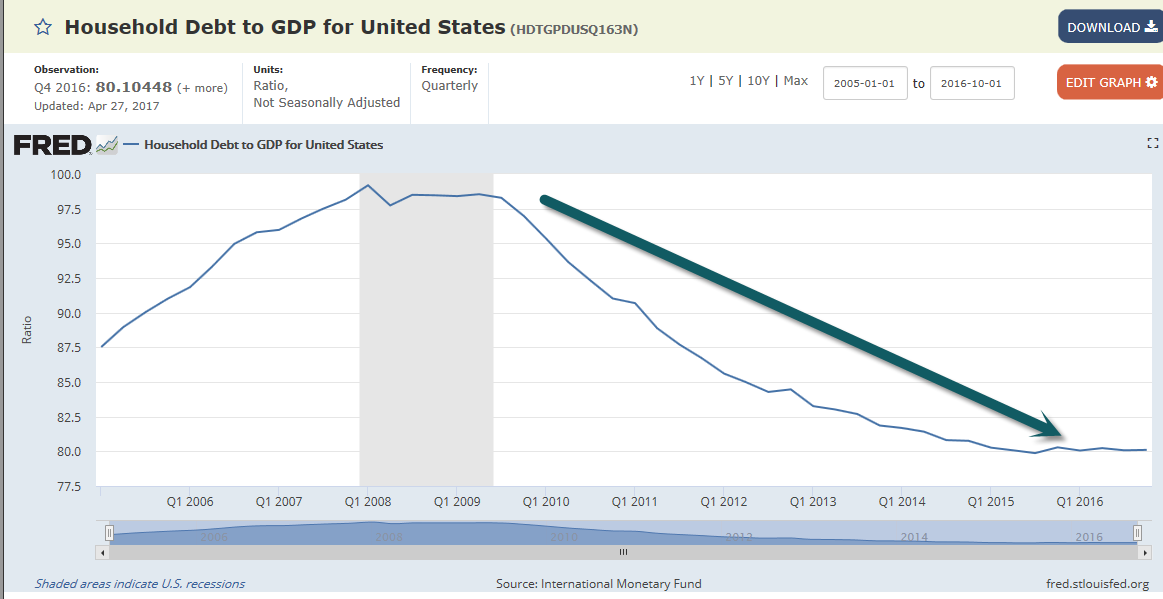

7.Headlines About Record Household Debt But It’s Most Because of Population Growth and Inflation. Household Debt to GDP Plummeted After 2008 Crisis and It Still Has Not Ticked Up.

A U.S. Household Sometimes Repays Its Debts

Carry the 1, subtract the two, and yup…that brings U.S. household debt to $13.2 trillion in Q1 2018—a record high. Well done America, we’ve done it again.

So what’s the breakdown?

- 67% mortgages, 10% student loans, 6% credit cards, 9% auto loans, and 8% other.

Now, you may start relapsing into Great Recession talking points: “Sound the alarms, housing bubble, subprime loans, The Big Short.” But there’s reason to remain level-headed.

Here’s what top economists have to say:

- This is normal: Debt levels tend to rise over time with inflation and population growth.

- The average credit score among new mortgage owners has jumped from 755 to 761.

- Mortgage rates just hit a 7-year high, aka fewer people will pull out their checkbooks.

On the flip side: 10% of student loan payments are 90 days overdue, while credit card and auto loan delinquency rates are rising.

Bottom line: The U.S. household debt picture isn’t perfect. But it’s not broken either.

8.-9. Read of the Day…The Inside Story of Wawa, the Beloved $10 Billion Convenience Store Chain Taking Over the East Coast

INC

By Maria AspanSenior editor, Inc.@mariaaspan

In February, a few days after the Philadelphia Eagles had won their first Super Bowl, a suburban convenience store celebrated. Hard.

The early-morning event nominally marked the reopening of the renovated store–a squat, tan outpost on a busy road–but it also doubled as an outpouring of football frenzy. Green-and-white noisemakers rattled. Eagles cheers punctuated the formal remarks. The mayor spoke, backed by rows of potato chips, while rush-hour commuters darted in for coffee and breakfast sandwiches. A towering goose mascot helped cut a big red ribbon.

In the backroom, wedged between computer servers and a first-aid kit, a brown packing box of Newport Menthol Gold at his feet, the man largely responsible for this $10 billion family empire grinned. “People ask what a non-executive chairman does. I tell them: Whatever he wants!” jokes Dick Wood, 80, who possesses, beneath the kindly exterior of a soft-spoken Florida retiree, a spine of steel. “I think I’m a myth.”

Among entrepreneurs, almost. Most family businesses don’t survive the third generation, yet Wood is comfortably watching his multi-generation company thrive. That would be Wawa, the much-beloved convenience store that you likely know either intimately or not at all.

Now Wawa’s semi-retired chairman, Wood was the second and longest-serving chief executive of a four-CEO company, one that has weathered 54 years of family in-fighting, recessions, and several failed expansion attempts. Wood kept Wawa private, but also started handing it off to non-family leaders more than a decade ago, betting the best way to ensure Wawa’s future was to separate it from its founding family. His wager paid off. Wawa is still aggressively growing: It now has almost 800 locations–none franchised–and 30,000 employees in six states (plus Washington, D.C.).

Wawa’s Playing FieldThe CompanyWawa claims $10 billion in annual revenue, which puts it among the top 20 U.S. chains tracked by Convenience Store News.The CompetitorsThe convenience store business–a $550 billion industry–is dominated by giants like the Japanese-owned 7-Eleven, which last year took in $29 billion from 8,700 North American outposts, and Alimentation Couche-Tard, the Quebecois owner of Circle K and Dairy Mart.The New RivalsFast food, old and new: Panera ($2.8 billion in revenue in 2016, before it sold for $7.5 billion to German conglomerate JAB), Dunkin’ Donuts ($860 million in revenue), Chipotle ($4.5 billion in revenue)–and even the fast-growing likes of Sweetgreen.

Founded in 1964 by Grahame Wood–Dick’s first cousin once removed–Wawa began as a roadside dairy market in the Philadelphia suburbs. Its founder likely wouldn’t recognize Wawa today, as it expands throughout the East Coast and audaciously tries to muscle out of the gas-station ghetto to compete with the likes of Panera, Starbucks, and Sweetgreen.

After decades of pushing cheap gas and cigarettes and made-to-order sandwiches to suburban crowds, Wawa is starting to

de-emphasize two of the three. The current CEO, Chris Gheysens, is swapping in Tesla charging stations, kale salads, and small-batch coffee, most of which customers can order on their phones (or Wawa’s ubiquitous touchscreens). Gheysens calls this Wawa’s “barbell” strategy: continue to offer the cheap staples that attracted longtime customers, while expanding into cities as the newest health-conscious, gourmet-inflected, casual-lunch option.

“We’ll open up a store this year in Center City Philadelphia that won’t sell cigarettes. It won’t have gas,” says Gheysens, 47, a South Jersey native who looks the part, down to his violet-and-black-plaid blazer and the big Eagles pennant in his pleasantly low-frills office. “When a convenience store doesn’t sell cigarettes and gas, that begins not to be a convenience store.”

That’s starting to become obvious throughout Wawa’s empire, including at the gleaming new complex looming over Red Roof, the family’s century-old estate at Wawa’s headquarters. The same split is visible at Wawa’s stores: The suburban pit stop whose reopening Dick Wood presided over is the ugly duckling to the swan–or goose; more on that later–near Washington’s Dupont Circle, a would-be gastropub with bar seating, brick walls, and industrial-chic exposed ceilings. (Face the Nation has a standing Sunday order.) The chain’s next planned flagship, in downtown Philadelphia, promises couches, café tables, “industrial and art deco elements,” vaulted ceilings, and a mural.

This is not Wawa’s first overhaul. “We’ve changed a lot over the years,” reflects Wood, who carefully orchestrated much of that change. But many of his efforts were internal, incremental; Gheysens is aiming at the most visible aspects of Wawa’s longtime–and fiercely beloved–identity.

I grew up with Wawa, but I wasn’t born into it. My Midwestern parents moved to Pennsylvania’s Delaware County, home to Wawa’s headquarters and many of its stores, when I was 6. Initially, we were confused by this “Wah-wah” that generated religious-level local fervor. (The name is taken from an Ojibwe word for the Canadian goose. Hence the goose logo and mascots.)

Soon enough, we became acolytes, won over by last-minute groceries and better-than-average coffee; my brothers, both now living far from Wawa outposts, still swear by its hoagies and breakfast sandwiches. But Wawa transcends local celebrity. “On their best day, most of the sub chains can’t top, for example, Wawa’s tuna hoagie on whole wheat,” Food & Wine recently declared. “Heaven, for a few bucks.” This year, Wawa achieved another level of pop-culture fame: During a pre-Super Bowl skit on Saturday Night Live, Tina Fey hoisted a basketful of Wawa hoagies to proclaim her Philly pride. And, like any all-night restaurant, the chain is always there to make fresh sandwiches for the closing-time crowd. “I feel like I should be too old to be winding up in Wawas at 1 a.m.,” one friend, a thirtysomething Wharton MBA student, recently sighed.

It’s not just the sandwiches that win notice. In 2005, Harvard Business Review singled out Wawa’s rigorous employee training and the resulting strong customer service culture. That training was developed through a proprietary program with Philadelphia’s St. Joseph’s University; the company now handles training on its own. “Nowhere else in my daily life does anyone hold open the door for me, except in a Wawa,” says Ronald Dufresne, a management professor at St. Joseph’s who worked on that program. “In a Wawa store, people are nice to each other.”

Like Wegmans or In-N-Out, Wawa is usually described as a cult brand, a regional player–a Mid-Atlantic specialist confined to a narrow niche. That niche, though, is huge. The company claims $10 billion in annual revenue. (Wawa also says it’s profitable, though it won’t discuss specifics or how much revenue comes from gas sales.) Top dog in the $550 billion U.S. convenience store industry is 7-Eleven, which took in $29 billion in U.S. revenue in 2017. But Wawa is now eyeing new competitors: quick-service and fast-casual chains like Dunkin’ Donuts or even Chipotle, which sells nearly $4.5 billion in burrito bowls and guacamole annually.

As Wawa edges upmarket, executives and fans cite a key advantage: its workers, their role in that company culture–and their financial stake, since Wawa is now 41 percent employee-owned. (See below.) Wawa asks employees to “fulfill lives, every day,” and promote six core values–one of which is “embrace change.”

“They do a great job,” says Bonnie Riggs, a restaurant analyst for NPD Group, who calls Wawa one of several “food-forward” convenience stores; others are Wawa’s in-state rival Sheetz, Baltimore’s Royal Farms, and Tulsa’s QuikTrip. All seek to compete with the “quick-service restaurants” that make up one of the fastest-growing and most-competitive segments of the restaurant industry. High-end chefs are spinning off fast-casual concepts; startups focused on salad and burgers and poke all vie to be the next Shake Shack; fast-food behemoths like McDonald’s and Dunkin’ Donuts are upgrading ingredients; grocery stores with prepared-food sections are becoming “grocerants.” (Seriously.)

Yet while it tries to level up, Wawa’s business still relies on volume and speed. The company makes “very few partial pennies per customer,” Gheysens says, “but for a lot of customers”–800 million of them annually. Bring people in for a cup of coffee or a tank of gas or to get cash at the store’s fee-free ATMs, and they’ll likely buy something else: a bag of chips, a Tastykake, a highly customized hoagie–or, since the prices are so low, all of the above. (An average convenience-store customer spends $4.12, according to NPD; Wawa says theirs spends $7.42.)

Wawa’s ability to sell so much so quickly relies on technology, tightly controlled supply-chain operations, and a “cluster” expansion strategy that establishes most new stores near other Wawas. The company introduced touchscreen ordering in 2002, getting a decade-long jump on the iPad menus that many fast-casual restaurants now use (reducing labor costs and making customized orders–and upselling–much easier). Its distribution partner, McLane, runs what Wawa calls the supplier’s only dedicated warehouse in the U.S., in New Jersey. Last year, Gheysens oversaw the launch of an oil barge and tug to bring 7.8 million gallons of gas from the Gulf of Mexico to Florida stores three times per month. The barge reportedly cost up to $80 million.

Given splurges like that–and the average $6 million per store Wawa is spending to open hundreds of Florida locations and establish itself in the pricier precincts of Washington–it’s a little astounding how cheap Wawa remains. Gheysens laughs, a little pained, when I mention a recent $10 Wawa dinner — including snack, drink and dessert — purchased in a part of D.C. not known for cheap eats. “We largely do not have a different urban pricing strategy,” says Gheysens, who’s spent most of his 21 years at Wawa in accounting and finance. “Consistency is really important to our customers.”

“In a Wawa, people are nice to each other,” says a professor who knows the company.

A one-time Deloitte analyst who became CEO in 2013, Gheysens took over in the midst of the company’s push into Florida. He’s continued that blitz while shifting his gaze to big cities: downtown Philadelphia, which the chain once neglected in favor of the suburbs and highways around them; D.C., a city long encircled by Wawas while lacking any at its core; potential new cities between Philadelphia and Wawa’s Florida beachheads; even, maybe someday, the food-and-retail gauntlet of New York.

“We are afraid to change much,” Gheysens says, while laying out ambitious plans to do just that. But Wawa has always been quietly reinventing itself.

“My father spent most of his career keeping the family out of the business.” That’s Rich Wood, Dick’s son and Wawa’s head of government relations and sustainability. “I was always told I would never be in the business by him. Constantly,” adds Rich, who left a role at Coca-Cola and spent two years pulling shifts in 24-hour Wawa stores before his dad let him into headquarters.

Dick Wood remains bluntly unsentimental about family and business. He and his brother George–also on the board–“decided a long time ago that what was important to the family was: ‘What’s the value of a share of stock, and what’s my dividend?’ ” Dick says. “The family is very happy to have somebody running the business who wants to grow the business.”

For the first 300 years or so, that was a Wood. Wawa was nominally founded in 1964, when Grahame Wood opened his first market in a rural suburb. But it really dates back to 1902, when Grahame’s grandfather George Wood opened the Wawa dairy farm, which would eventually supply that store. And to 1803, when George’s uncle David C. Wood opened the first of the New Jersey iron foundries that would eventually provide the capital to buy the dairy. And to 1682, when the first Richard Wood came from England to colonial Philadelphia (at the same time as fellow Quaker William Penn) and started building a dynasty. It went on to encompass textile companies, children’s hospitals, the Pennsylvania Railroad, the Philadelphia Bank, and a dry goods business that, in the late 1830s, outsourced some debt-collection work in Illinois to a young lawyer named Abraham Lincoln.

(The Woods also intersected with other local, politically-connected dynasties; the du Ponts, of chemical fame, and the McNeils, of Tylenol fortune, both have supporting roles in the Wawa story.)

By the early 1960s, as supermarkets started to eat into his dairy’s home-delivery business, Grahame Wood had begun researching convenience stores, visiting a friend who owned some in Ohio. He returned with a plan to open three stores that would sell Wawa’s milk and other perishables.

“He was a man who could roll up his sleeves,” recalls Maria Thompson, an architectural historian who married Grahame’s nephew and serves as Wawa’s corporate historian. She credits the company’s management culture to “Uncle Grady’s” paratrooper service during World War II: “There’s this sense of building a team, where I’m relying on you for my life,” she says. “It’s never one person who’s responsible.”

In 1970, Grahame hired his cousin’s son, Richard D. Wood Jr.–Dick–a young lawyer who’d advised companies on mergers and acquisitions and IPOs.

Which was perfect training. “I formed a really negative reaction to being public,” Dick says. “I don’t think we could have driven the company to the size it is, with the culture it has, without being a private company. You’re making short-term decisions, and we are focused on long-term decisions.” (Gheysens agrees, saying he’s “publicly, on the record,” not interested in an IPO.)

Grahame named Dick to succeed him in 1977 and died in 1982. In his 2014 company bible, The Wawa Way, former CEO Howard Stoeckel recounts a story Dick repeated: On his final trip home from the hospital, Grahame asked his ambulance driver to stop at a Wawa construction site. He wanted to check on the progress.

Dick Wood spent the 1980s and 1990s expanding Wawa’s product lineup beyond dairy and deli meats, gradually transforming Wawa from quasi-grocery to sandwich shop. His early attempt at selling gas flopped; the second, in 1993, succeeded, ushering in what Gheysens calls the era of “big gas” and suburban-focused expansion. “You have to give them credit for having a really good business, but not standing pat, and incrementally changing to comport with how the customers are changing,” says John Stanton, a food marketing professor at St. Joseph’s who’s consulted for Wawa.

Wawa spent a lot of the 1990s learning from failure, like a short-lived attempt to sell products from Taco Bell and Pizza Hut–what The Wawa Way generously, if rather inelegantly, considers “ethnic food.” (Today, Wawa’s best food remains proudly basic: turkey hoagies, soft pretzels, croissant-egg-cheese breakfast sandwiches.)

Dick Wood also spent the 1990s figuring out how to manage his family. Wawa ownership was mostly split between two separate family trusts, and one trustee started trying to force a sale or an IPO. In 1998, the company sold a stake to an investment group controlled by the McNeil family–the Tylenol heirs–who, within five years, tried to force Wawa to go public.

Fortunately, Dick had a backup plan, one he’d started setting up in 1992 to reward longtime employees and start cashing out his family: an employee stock-ownership program, or ESOP. Wawa bought back the McNeils’ stake for $142 million, and asked employees to start switching some of their retirement funds from Wawa’s 401(k) plan to the ESOP. The workers did. Fifteen years later, many are retiring as millionaires.

Which is to say that Dick–who comes off as a warm, funny, and slightly fragile senior citizen, who carefully unbuckled his briefcase to share a glossy, seven-page family tree–is also a sharp and ruthlessly smart strategist. Wawa’s six core values include the inoffensive “passion for winning.” Dick argued for the tougher “never be satisfied.” He also delayed his retirement in part because “I wanted to make sure one of our vice presidents retired,” Dick recalls. “He did!”

In the early 2000s, Dick also gave interviews for articles that named his nephew, Wawa’s then-president and CFO, Thère du Pont–yes, of those du Ponts–as his successor. But when he retired in 2005, Wood instead appointed the first outsider CEO: Howard Stoeckel, a former human resources executive at the Limited, who joined Wawa in 1987 and rose to become its enthusiastically folksy marketer in chief. Du Pont “was smart, but values and culture mean more in this company than being smart,” Dick says. (Thère du Pont did not respond to requests for comment.)

While not a family member, Stoeckel was a well-known quantity to Wawa employees. He approached the job with a healthy appreciation for Wawa’s culture, and with a philosophy that continued laying the groundwork for Gheysens. “I realized I had to be willing to try things,” Stoeckel says. “Not everything would work, but we don’t penalize failure here. If you learn from failure, you’re rewarded.”

Stoeckel’s biggest practical goal was overseeing Wawa’s first major geographic jump, to Florida, where Wawas started opening in 2012. While far from Wawa’s supply chain and store clusters, the Sunshine State was otherwise welcoming: a big territory, affordable real estate, an established convenience-store culture, and many transplants from Wawa’s home turf–including one Dick Wood.

At 59, when he became CEO, Stoeckel soon started looking for a successor. The board settled on Gheysens, who grew up working in his father’s car wash. After graduating from Villanova, Gheysens went to Deloitte, where Wawa became a client. He jumped to the retailer in 1997 and worked his way up to CFO.

Five years after formally taking over, Gheysens regularly consults with his two immediate predecessors–even when he’s departing from their longstanding suburban strategy. “We are a big test-and-learn organization,” he says.

The first test of his urban pivot came when he persuaded Wawa’s board to sign off on a big new store in Center City Philadelphia–and built it within 85 days, ahead of the crowds who flocked to the pope’s 2015 visit to the city. The bet, and hustle, paid off. “We’re about 50 percent higher than we thought we’d be, in terms of sales and volumes,” Gheysens says. “There could be more–we’re just maxed out.” Suddenly, Wawa had a new focus: cities, and their food-savvy residents.

Half a mile from the renovated Wawa’s celebrations, at a larger, newer Wawa with gas pumps outside and tables out back, training general manager Denise Haley is overseeing operations. A cheerfully competent presence with carefully plucked eyebrows and long brown hair, Haley walks me through industrial kitchens, past cold cases full of energy drinks and a freezer holding Halo Top and Wawa ice cream. She greets colleagues and customers without breaking stride, and then throws a smile to the visiting cigarette sales reps. “They pay us a lot of money,” she confides.

Haley started at Wawa in 1994, and is in all respects a company lifer. After asking where I grew up, she quickly identifies the closest Wawa. “Oh, store 54!” she rattles off. Then: “That’s Paul’s store. My brother was married to his sister.”

She also makes a few appearances in The Wawa Way, as a paragon of Wawa’s customer service. In one anecdote, Haley made a house call to a regular, an 89-year-old woman who fell and contacted the Wawa for help, and drove her to the ER.

Beyond the occasional book cameo, or an annual resort trip for top managers, Haley and other longtime employees have been well rewarded for their tenures at Wawa, thanks to the company’s ESOP, which, by some accounts, is the second-largest in the U.S. This setup isn’t without tensions; as Wawa’s growth has accelerated, so have payouts. Wawa recently agreed to pay $25 million to settle a lawsuit from former employees that claimed that after they left, the company prematurely cashed them out of the ESOP. (Wawa declined to comment.) That lawsuit, and a few others involving overtime and racial discrimination claims at individual stores, point to another challenge: Wawa’s labor force has increased dramatically in recent years. Wawa had 20,000 employees when Gheysens took over in 2013; it now employs more than 30,000 people–and 5,000 more in summer.

Wawa says its turnover rate is lower than average for retail, a sector with a notoriously high churn. But as the company continues to expand, and does so without franchising, Wawa must figure out how to maintain its employee training and its customer service reputation at massive scale.

“Probably the thing that makes Wawa the hardest is making sure you have the right people at all times,” Gheysens acknowledges. “Wawa’s hard to work in.”

Another big issue: Technology, especially as Amazon, with its no-checkout stores and its takeover of Whole Foods, attempts to overshadow the brick-and-mortar retail ecosystem. After Wawa’s long-ago bet on touchscreen ordering, Gheysens has introduced mobile ordering and delivery, through a partnership with Grubhub.

But perhaps the most immediate challenge will be finding the right balance for Gheysens’s barbell. One end is obvious: Within the past year, Wawa has introduced “reserve” coffee sourced from small-batch beans from Kenya and Tanzania. Some stores have salad counters that could compete with those at Chopt or Sweetgreen. And the company is developing “artisan sandwiches” that have what Gheysens calls “really high-end” meats–and higher prices.

Yet Wawa can’t ignore longtime customers. Their loyalty helped Wawa sell 80 million hoagies and 200 million cups of coffee last year–and can generate reactions like Philadelphia magazine’s grumbling over declining hoagie quality, or the great hazelnut decaf backlash of 2009, when Wawa discontinued a lower-selling blend and promptly “got blasted,” Gheysens recalls. He’s trying to avoid a repeat.

Most of the heavy lifting happens at Wawa’s gleaming new headquarters, in a 10,000-square-foot test kitchen populated by chefs, nutritionists, food scientists, and beverage specialists. One recent day, an employee offers tastes of the sesame-seed hoagie rolls she’s rigorously comparing, before Wawa’s beverage expert walks me through a small-batch “cupping,” the coffee snob’s sniff-slurp-spit equivalent of a wine tasting. Meanwhile, two chefs study an array of chickpeas, scallions, and lemons, ready to experiment with a “green tehina” sauce that, one admits, “is a bit out there for our customers.”

Which won’t necessarily stop Wawa from trying to sell it–so long as it can fit into what Gheysens declares to be the end goal of all of this transformation. “We are proudly a convenience store,” he says. “We just want to be the best one.”

How Wawa stayed private–and how its workers won.

About 14.4 million American workers participated in employee stock ownership programs (ESOPs) as of 2015, up from 10.2 million in 2002, according to the National Center for Employee Ownership. The overall number of plans has declined, which the NCEO attributes to inactive plans some companies registered in the late 1990s, as well as low creation rates since then.

“What you want in a corporate culture with an ESOP is a lot of ‘in the same boat’ identification between all the workers and managers,” says Joseph R. Blasi, director of Rutgers University’s Institute for the Study of Employee Ownership and Profit Sharing. “You want the company using the workers as a consumer brand, which Wawa does–it’s all over their stores.”

ESOPs work like this: Once an employee has worked for a specified time and/or hours, a company starts buying shares for that employee, often using credit. (At Wawa, anyone who’s worked more than a year, who’s logged at least 1,000 hours, and who’s at least 18 is enrolled.)

Shares rise or fall with company fortunes; their prices must be reported. When a worker retires, or within six years of leaving, the company must start paying the shares’ current value. A Wawa share was about $900 when its ESOP expanded in 2003. It’s now worth almost $10,000.

Which has paid off handsomely for longtime employees like Cheryl Farley, who started part time at Wawa in 1982. In April, she retired from the IT department at age 58–and promptly embarked on a busy schedule of birding trips around North America; cruising Alaska and the Caribbean; and visits to fellow Wawa retirees, some of whom built beach houses with ESOP earnings. “Because of the ESOP, many recent retirees are doing things that many people would never dream of,” Farley says. “I’m healthy, I’m young and I get to relax.”

https://www.inc.com/magazine/201806/maria-aspan/wawa-convenience-store-pennsylvania.html?cid=hmside4

10.3 Time Management Tips That Actually Work

By James Clear | Minimalism, Procrastination, Productivity, Self-Improvement

Time management can be tough. What is urgent in your life and what is important to your life are often very different things.

This is especially true with your health, where the important issues almost never seem urgent even though your life ultimately hangs in the balance.

- No, going to the gym today isn’t urgent, but it is important for your long–term health.

- No, you won’t die from stress today, but if you don’t get it figured out soon, you might.

- No, eating real, unprocessed foods isn’t required for you to stay alive right now, but will reduce your risk of cancer and disease.

Is there anything we can do? If we all have 24 hours in a day, how do we actually use them more effectively?

And most importantly, how can we manage our time to live healthier and happier, do the things that we know are important, and still handle the responsibilities that are urgent?

I’m battling with that answer just like you are, but in my experience there are three time management tips that actually work in real life and will help you improve your health and productivity.

Before we talk about how to get started, though, I wanted to let you know I researched and compiled science-backed ways to stick to good habits and stop procrastinating. Want to check out my insights? Download my free PDF guide “Transform Your Habits” here.

- Eliminate half–work at all costs.

In our age of constant distraction, it’s stupidly easy to split our attention between what we should be doing and what society bombards us with. Usually we’re balancing the needs of messages, emails, and to–do lists at the same time that we are trying to get something accomplished. It’s rare that we are fully engaged in the task at hand.

I call this division of your time and energy “half–work.”

Here are some examples of half–work…

- You start writing a report, but stop randomly to check your phone for no reason or to open up Facebook or Twitter.

- You try out a new workout routine. Two days later, you read about another “new” fitness program and try a little bit of that. You make little progress in either program and so you start searching for something better.

- Your mind wanders to your email inbox while you’re on the phone with someone.

Regardless of where and how you fall into the trap of half–work, the result is always the same: you’re never fully engaged in the task at hand, you rarely commit to a task for extended periods of time, and it takes you twice as long to accomplish half as much.

Half–work is reason why you’re able to get more done on your last day before vacation (when you really focus) than you do in the 2 weeks previous (when you’re constantly distracted).

Like most people, I deal with this problem all of the time and the best way I’ve found to overcome it is to block out significant time to focus on one project and eliminate everything else.

I pick one exercise and make it my only focus for the entire workout. (i.e. “Today is just for squats. Anything else is extra.”)

I carve out a few hours (or even an entire work day) to deep dive on an important project. I’ll leave my phone in another room and shut down my email, Facebook, and Twitter.

This complete elimination of distractions is the only way I know to get into deep, focused work and avoid fragmented sessions where you’re merely doing half–work.

How much more could you achieve if you did the work you needed to do, the way you needed to do it, and eliminated the half–work, half–wandering that we fill most of our days with?

- Do the most important thing first.

Disorder and chaos tend to increase as your day goes on. At the same time, the decisions and choices that you make throughout the day tend to drain your willpower. You’re less likely to make a good decision at the end of the day than you are at the beginning.

I’ve found that this same trend holds true in my workouts as well. As the workout progresses, I have less and less willpower to finish sets, grind out reps, and perform difficult exercises.

For all of those reasons, I do my best to make sure that if there is something important that I need to do, then I do it first.

If I have an important article to write, I grab a glass of water and start typing as soon as I wake up. If there is a tough exercise that I need to do, then I do it at the beginning of each workout.

If you do the most important thing first, then you’ll never have a day when you didn’t get something important done. By following this simple strategy, you will usually end up having a productive day, even if everything doesn’t go to plan. If you actually do the most important thing first each day, it is the only productivity tip you’ll ever need.

- Reduce the scope, but stick to the schedule.

I’ve written previously about the importance of holding yourself to a schedule and not a deadline. There might be occasions when deadlines make sense, but I’m convinced that when it comes to doing important work over the long–term, following a schedule is much more effective.

When it comes to the day–to–day grind, however, following a schedule is easier said than done. Ask anyone who plans to workout every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday, and they can tell you how hard it is to actually stick to their schedule every time without fail.

To counteract the unplanned distractions that occur and overcome the tendency to be pulled off track, I’ve made a small shift in how I approach my schedule. My goal is to put the schedule first and not the scope, which is the opposite of how we usually approach our goals.

For example, let’s say you woke up today with the intention of running 3 miles this afternoon. During the day, your schedule got crazy and time started to get away from you. Now you only have 20 minutes to workout.

At this point, you have two options.

The first is to say, “I don’t have enough time to workout today,” and spend the little time you have left working on something else. This is what I would usually have done in the past.

The second option is to reduce the scope, but stick to the schedule. Instead of running 3 miles, you run 1 mile or do five sprints or 30 jumping jacks. But you stick to the schedule and get a workout in no matter what. I have found far more long–term success using the this approach than the first.

On a daily basis, the impact of doing five sprints isn’t that significant, especially when you had planned to run 3 miles. But the cumulative impact of always staying on schedule is huge. No matter what the circumstance and no matter how small the workout, you know you’re going to finish today’s task. That’s how little goals become lifetime habits.

Finish something today, even if the scope is smaller than you anticipated.

Time Management Tips That Actually Work

There are thousands of time management apps and productivity gadgets. You’ll find more calendars, reminders, and task lists than you know what to do with. But in my experience, the most effective and practical time management approaches are simple.

When it comes to living a healthy and productive life, I do my best to focus on three things…

- Eliminate half–work and focus deeply.

- Do the most important thing first.

- Stick to your schedule and build the habit, no matter how small the accomplishment.

How have you managed your time better and accomplished more at work, at home, or in the gym?