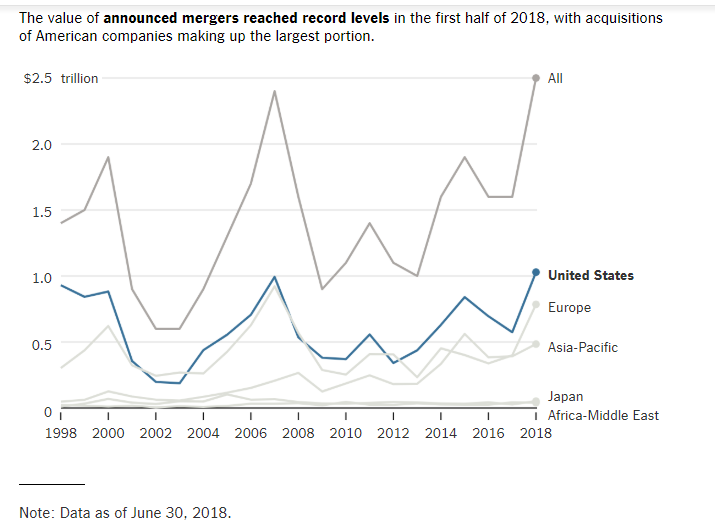

1.A Record $2.5 Trillion in Mergers Were Announced in the First Half of 2018

By Stephen Grocer

July 3, 2018

More than $2.5 trillion in mergers were announced during the first half of the year, as fears of Silicon Valley’s growing ambitions helped drive a record run of deal-making.

Four of the 10 biggest deals were struck in part to fend off competition from the largest technology companies as the value of acquisitions announced during the first six months of the year increased 61 percent from the same period in 2017, according to data compiled by Thomson Reuters. That has put mergers in 2018 on pace to surpass $5 trillion, which would top 2015 as the largest yearly total on record.

Even rising global trade tensions did not manage to stifle acquisitions: Deals involving companies based in different countries nearly doubled compared with the first half of last year, and accounted for more than 40 percent of all announced transactions.

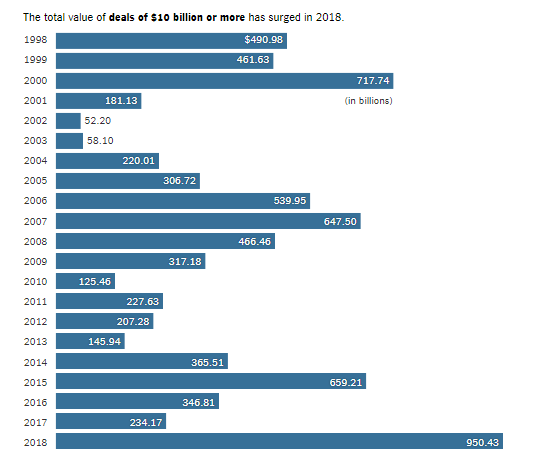

2.Equity Volatility Returns to Normal

State Street

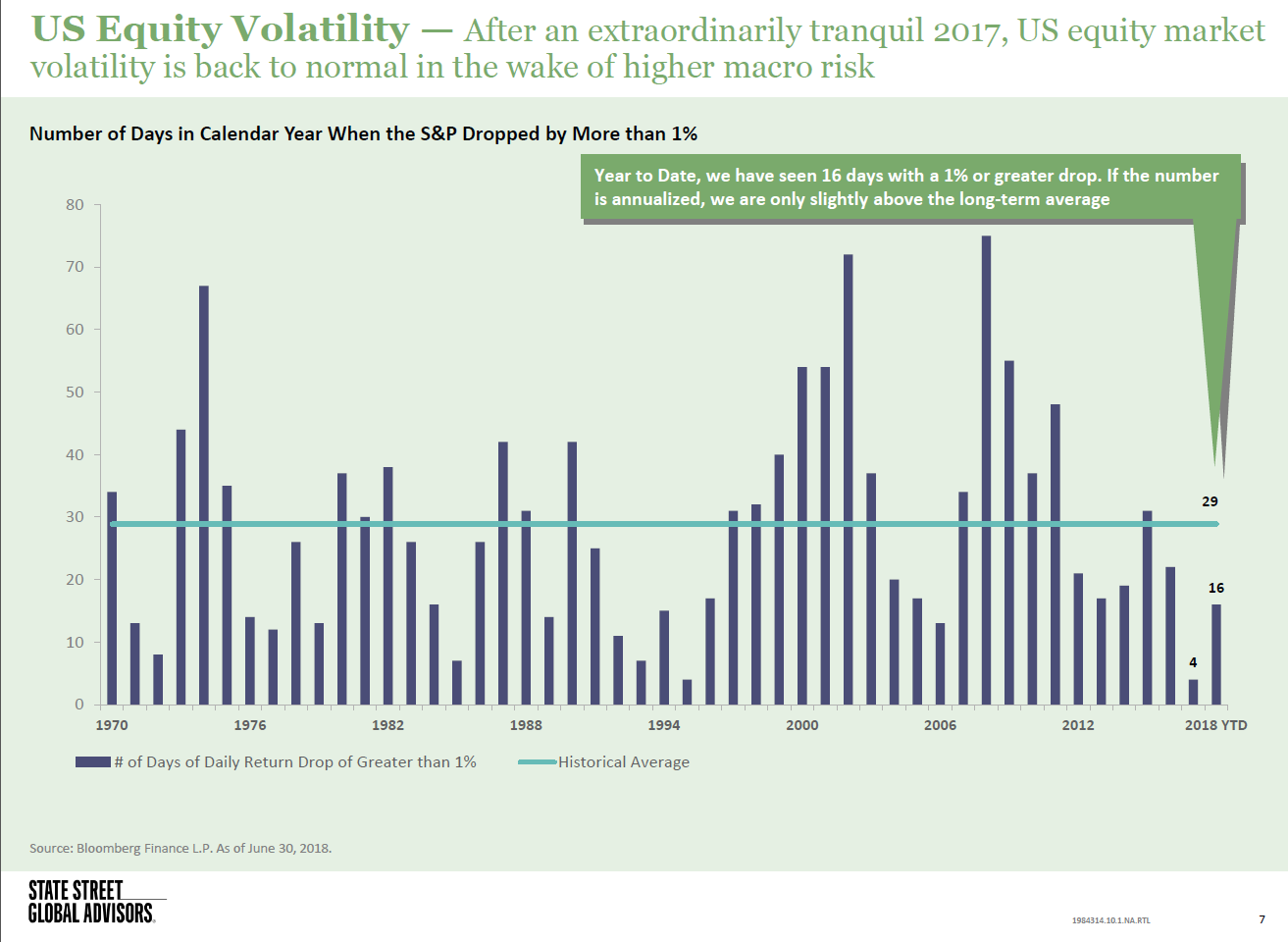

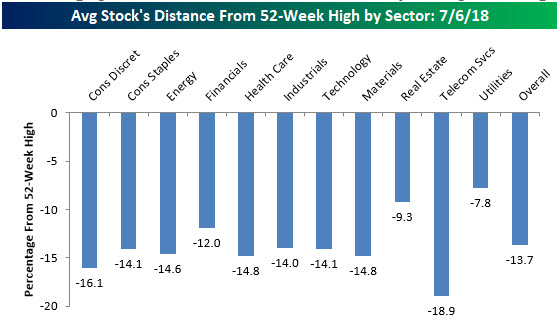

3.Average Stock Declines From Their 52-Week Highs

Jul 6, 2018

In a tweet yesterday, we noted that the S&P 500 was trading right at the exact mid-point of its 2018 closing high and closing low, putting the index about 5% below its 52-week high. While that’s a relatively modest decline, stocks in the S&P 1500, which includes large, mid, and small caps, are down an average of 13.7% from their respective 52-week highs. Before we all go and start talking about how these numbers suggest much weaker internals than the overall market averages suggest, keep in mind that not all stocks hit their own highs simultaneously with the market. Therefore, this reading is always weaker than the overall reading for the S&P 500. In fact, even when the S&P 500 was hitting highs earlier this year, the average stock in the index was down in the mid to high single-digits.

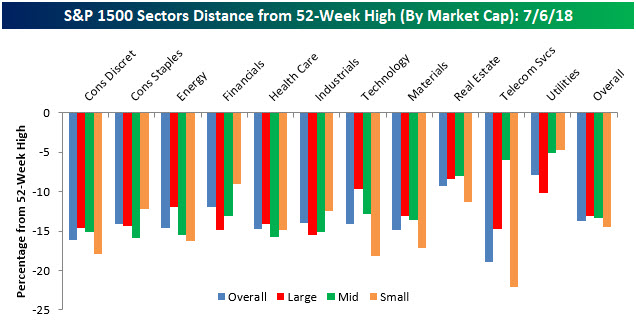

What is interesting to note about current levels is how uniform they are across each market cap range. Between the average large cap, which is down 13.1% from its high, and the average small cap, which is down 14.4%, only 1.3 percentage points separates the two. Normally the gap is much wider (with small caps usually down much more), but with small cap domestically focused stocks outperforming recently, the gap has narrowed.

In terms of average stock declines by sector, the handful of stocks in the Telecom Services sector are down the most with an average decline of 18.9% from their respective highs. Behind that sector, you may be surprised to see that the next weakest sector based on this measure is Consumer Discretionary, where the average stock is down over 16%. Consumer Discretionary has been one of the better performing sectors this year with a gain of 11%. A lot of that strength, however, is the result of big gains in Amazon.com (AMZN) and Netflix (NFLX), which have large weightings in the market cap weighted sector performance. Among smaller cap names in the sector, the picture isn’t quite as strong.

Sectors holding up the best relative to their highs are Utilities (-7.8%) and Real Estate (-9.3%). These are the only two sectors where the average stock is down less than 10%, and that’s largely due to the fact that both sectors are defensive and not very volatile by nature. Stocks in these two sectors may well be holding up the best, but both sectors are actually underperforming the S&P 500 YTD.

Finally, our last chart breaks down the average decline from a 52-week high by sector and market cap. Here there are some interesting divergences. We already mentioned the Consumer Discretionary sector above, but a similar dynamic is playing out in Energy, and even more so in Technology. Within the Technology sector, the average decline from a 52-week high among large caps is less than 10%, while the average decline for a small cap is more than twice that at 18.2%. Besides small cap tech, the only group weaker has been small cap Telecom Services, which is made up of just eight stocks compared to 95 for the small cap Technology sector.

While large caps are holding up a lot better than small caps in many sectors, we have seen the opposite pattern play out in the Financials sector. All we seem to hear this year is how Financials have been so weak, and while that may be true among large cap Financials which are down an average 14%+ from their highs, small cap Financials are down less than 10%.

https://www.bespokepremium.com/think-big-blog/

4.Utes and Real Estate Lead Returns in Last 30 Days.

IWM closed just below all-time highs around $170 Friday, while that INDU back over 200d, but failed the 100d. Oil lost ground last week, the first time in 3 weeks, while Soybeans had a huge rally, shrugging off Tariff Angst, as DSIs had fallen near 5% Bulls. Once again, look how oversold Financials are coming into earnings….

From Dave Lutz at Jones Trading

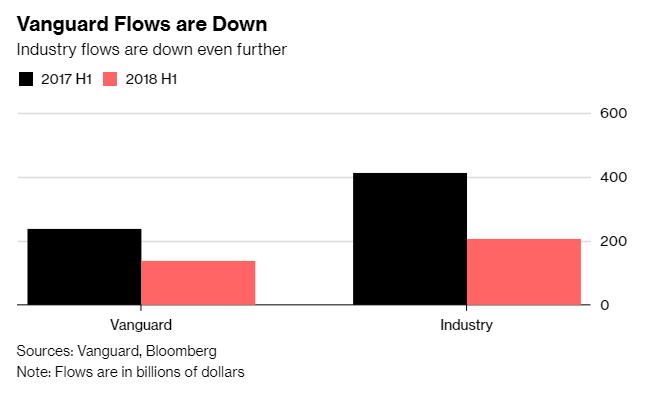

5.Vanguard Flows in First Half Down 42% Year Over Year….Total U.S. Flows Down 50%.

Vanguard Isn’t Taking in as Much Money; Neither Is Anyone Else

By Charles Stein

July 6, 2018, 11:36 AM EDT

Fund flows to money managers slowed across industry in 2018

Declines may be tied to so-so performance of stock market

Vanguard Group is attracting a lot less money from investors this year compared with 2017. Turns out, the mutual fund giant’s not alone.

Vanguard, the world’s second-largest money manager, collected $138 billion in the first half of 2018, down from $237 billion in the same period a year ago, according to the firm. That’s a decline of 42 percent. By comparison, total U.S. fund flows — money going into exchange-traded, active and passive mutual funds — fell roughly 50 percent, according to Bloomberg estimates.

Vanguard Flows are Down

Industry flows are down even further

Sources: Vanguard, Bloomberg

Note: Flows are in billions of dollars

“At first glance it looks like Vanguard is having an off-year, but relatively speaking their dominance is still intact,” said Eric Balchunas, senior ETF analyst with Bloomberg Intelligence.

The reason for the drop-off in overall flows? The so-so performance of the stock market, said Balchunas, who points out that there is a strong correlation between market returns and fund flows. The S&P 500 Index rose 2.7 percent in this year’s first half compared with 9.3 percent in the first six months of last year.

— With assistance by James Seyffart, and Mary Romano

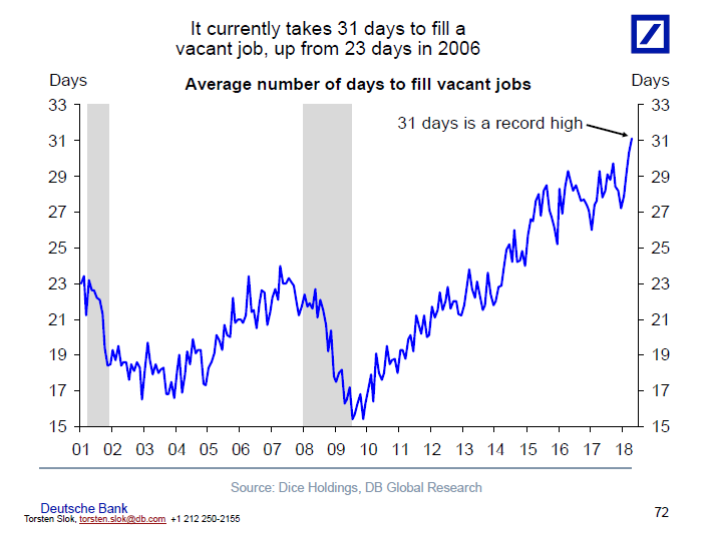

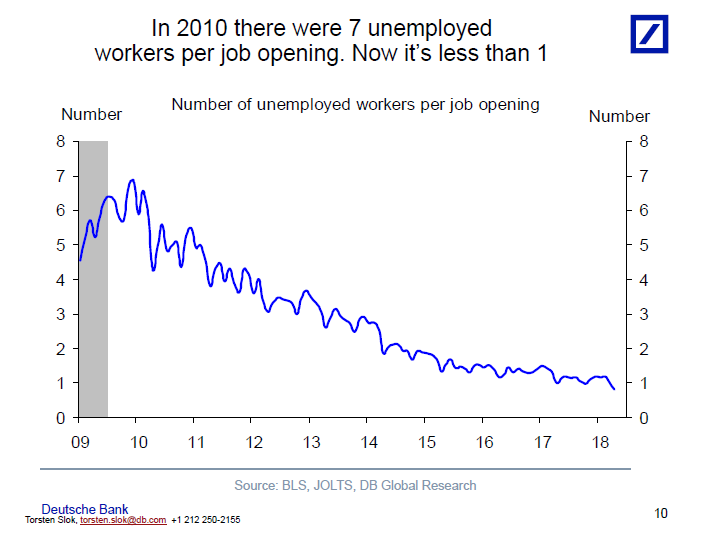

6.Average Number of Days to Fill a Vacant Job

It currently takes 31 days on average to fill a vacant job, see chart below, and also our latest labor market chart book here.

Torsten Sløk, Ph.D.

Chief International Economist

Managing Director

Deutsche Bank Securities

60 Wall Street

New York, New York 10005

Tel: 212 250 2155

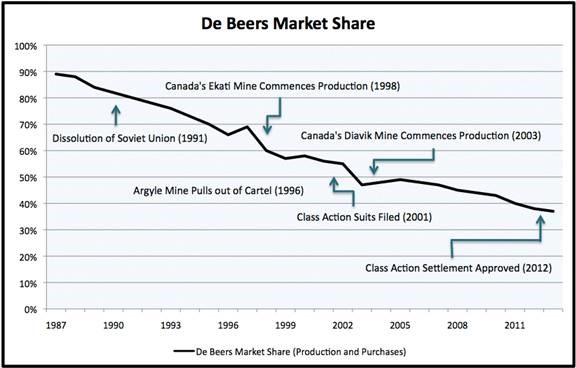

7.Interesting Stat of Day…De Beers Diamonds Had 90% Market Share Up to 1980’s

http://www.kitco.com/ind/Zimnisky/2013-06-06-A-Diamond-Market-No-Longer-Controlled-By-De-Beers.html

TIF 40% Gap up from 2018 lows.

8.Manhattan real estate has worst second quarter since financial crisis

Manhattan real estate had its worst second quarter since the financial crisis, according to a report from Douglas Elliman and Miller Samuel Real Estate Appraisers and Consultants.

Average sales prices fell 5 percent to $2.1 million.

Total sales in Manhattan fell 17 percent from the prior year.

Robert Frank | @robtfrank

Published 12:01 AM ET Tue, 3 July 2018 Updated 3:49 PM ET Tue, 3 July 2018CNBC.com

Manhattan apartment buildings

Manhattan apartment buildings

Manhattan real estate had its worst second quarter since the financial crisis, with prices and sales dropping and inventory rising, according to a new report.

Total sales in Manhattan fell 17 percent in the second quarter from a year ago, according a report from Douglas Elliman and Miller Samuel Real Estate Appraisers and Consultants. The average sales price fell 5 percent to $2.1 million.

Brokers blamed the decline partly on bad weather and other temporary factors. But analysts say the market is facing bigger pressures, from a huge pipeline of new condos to a dwindling number foreigner buyers, volatile stock markets and new tax changes that make New York less attractive.

While Manhattan is still a prime market with plenty of demand, the cooling sales suggest that the sky-high prices of 2015 and 2016 still have further to fall to meet today’s more price-conscious buyers.

“The market is resetting to a lower, more long-term level of activity,” said Jonathan Miller, CEO of the appraisal firm Miller Samuel.

One of the biggest problems is the glut of new condos under construction, especially in the luxury segment. The inventory of luxury apartments for sale jumped 10 percent to its highest level for a second quarter in seven years. There is now a 16-month supply of luxury units, according to the report, and luxury apartments are sitting on the market an average of more than six months.

Uncertainty around the economy and new tax law is also crimping sales. The tax revamp limits federal deductions for state and local taxes and makes high-tax states like New York less attractive. While some forecasts say the change could slice 10 percent off the value of New York real estate, the ultimate impact is still unknown, Miller said.

“Everyone is just dancing around the impacts right now,” he said. “I don’t think it will really be clear to people until they write that (tax) check next April.”

Finally, foreign buyers are less of a force than they were in 2014 and 2015. With overseas economies slowing, and the U.S. and other countries cracking down on the use of real estate for money laundering or offshoring, the share of apartments being sold to foreign buyers has fallen by about 40 percent, Miller said.

All those factors will continue to weigh on prices and sales this year.

“I think the market is just moving sideways,” he said.

9.Read of the Day…Immeasurably Important

Jul 5, 2018 by Morgan Housel

Robert McNamara was hired by Henry Ford II to help turn Ford Motor around. Ford was losing money after World War II and needed a “whiz kid” – that’s what Henry Ford called it – who saw running a business as an operations science, driven by the ice-cold truth of statistics.

McNamara took that skill to Washington when he became Secretary of Defense. Ken Burns’ documentary on the Vietnam War describes McNamara’s philosophy:

Robert McNamara vowed to make America’s military be cost effective. He demanded that everything be quantified. Commanders dutifully complied. He and his staff generated mountains of daily, weekly, monthly, and quarterly data on hundreds of separate indicators – far more data that could ever be adequately analyzed.

But the strategy that worked at Ford had a flaw at the Department of Defense. Rufus Phillips, a former CIA agent, describes in the documentary where McNamara’s management strategy backfired during the Vietnam War:

Secretary McNamara decided that he would draw a chart to determine whether we were winning [Vietnam] or not.

He was using things like the numbers of weapons recovered, numbers of Viet Cong killed, numbers of Viet Cong defectors. Very statistical.

He asked Edward Lansdale, head of special operations at the Pentagon, to come down. He said, “Look at this [data].” Lansdale looked, and he said, “There’s something missing here.”

McNamara said, “What?”

Landsdale said, “The feelings of the Vietnamese people.”

You couldn’t reduce that to a statistic.

This was a central issue with managing the Vietnam War. The difference between battle statistics brought to Washington and the feelings among those involved could be 10 miles apart.

General Westmoreland, who commanded U.S. forces, told Senator Fritz Hollings, “We’re killing these people [Viet Cong] at a rate of 10 to 1.” Hollings replied, “The American people don’t care about the 10. They care about the 1.”

Ho Chi Minh put it more bluntly: “You will kill ten of us, and we will kill one of you, but it is you who will tire first.”

Hard to contextualize that on a chart.

Some things are immeasurably important. They’re either impossible, or elusive, to quantify. But they can make all the difference in the world, often because their lack of quantification causes people to discount their relevance, or even deny their existence.

Lehman Brothers was in great shape on September 10th, 2008. That’s what the statistics said, anyway.

Its Tier 1 capital ratio – a measure a bank’s ability to endure loss – was 11.7%. That was higher than the previous quarter. Higher than Goldman Sachs. Higher than Bank of America. Higher than Wells Fargo. It was more capital than Lehman had in 2007, when the banking industry and economy were about the strongest they had ever been.

Four days later, Lehman was bankrupt.

The most important metric to Lehman during this time was confidence and trust among short-term bond lenders who fed its balance sheet with capital. That was also one of the hardest things to quantify.

You could try to measure trust with bond spreads, but that was imperfect. Short-term trust is like musical chairs – only measured at a moment of truth while otherwise giving the impression that everyone is having a good time. In hindsight, we know bond investors were losing faith throughout 2008. But the music was playing, so they kept lending. Then one morning they got scared and ran off.

You can’t measure what’s going on inside people’s heads to know when or why that happens.

And this stuff happens a lot.

Two things in business and investing tend to be immeasurably important.

The stickiness of support from customers, employees, and investors. Measuring why they feel the way they do and when they’ll start feeling something different.

Chris Rock once described the careers of musicians: “Here today, gone today.” This is partly due to one-hit wonders. But tastes also change. Or sometimes they do. We got sick of the Backstreet Boys, but Madonna became timeless. Seven years into their careers, each had sold about the same number of records: 70 million. Then fans kept lining up for one and left the other. Very difficult to measure how and why that happens, or when it will. Taste is not a science, and predicting taste’s change is close to sorcery. Asset bubbles work the same way. You can measure everything about a bubble except the most important part: When investors will stop believing in it. The end of the bubble is just the end of enthusiasm. And enthusiasm isn’t a tamable statistic. It’s a hormone that owes nothing to the logic of your data.

Whether the act of measuring something has an impact on what you’re measuring, like capitalism’s version of Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle.

Give a smart person a big incentive to increase sales in a short period of time, and they’ll probably do it. But a relentless focus on sales numbers does more than track sales. It changes how sales are done, how customers are treated, what kind of customers you’re willing to partner with, how sales are accounted for, when they’re logged, how the product is produced, etc. Measuring induces incentives, and incentives impact everything. Recent example: “Tesla stopped a ‘brake and roll’ test as it pushed to hit Model 3 goals.”

What’s hard to measure is whether the act of measuring something today changes how it’s done in a way that will affect tomorrow. It shouldn’t be hard to measure that, but it is in practice. If your goal is to make a metric go up, the temptation is to declare victory when it does, without digging deeper to look for collateral damage. The most common error here is focusing on rising sales as the end-all metric without realizing that pushing sales through aggressive promotions or high-pressure marketing can turn off customers, and turned-off customers are the strongest anchor on future sales. Another is the relentless pursuit of high profit margins. That can, when achieved by lower investment or cutting corners, come at the expense of profits. Jeff Bezos explained:

Percentage margins are not one of the things we are seeking to optimize. It’s the absolute dollar free cash flow per share that you want to maximize. If you can do that by lowering margins, we would do that. Free cash flow – that’s something investors can spend.

The point here is that investing is both art and science. Some things are countable. Others you have to just feel out.

Gathering information is a science. Filtering out noise is an art.

Net present value is a science. Identifying the trust and passion of a CEO is an art.

Measuring what worked in the past is a science. Understanding why things are different now is an art.

Since those are conflicting skill sets, toggling between the two is hard. Which is why business and investing is hard. Steve Jobs was both a technical and artistic genius. Warren Buffett can calculate DCF figures in his head, but he also drops fluffy feelings like, “With Coke, it’s not about share of market; it’s about share of mind.” That kind of mental flexibility is a rare trait.

If you think the world is all art you’ll miss how much stuff is too complicated to think about intuitively. Most people get that. But if you think the world is all data you’ll miss how much is too complicated to summarize in a statistic. That one’s a little harder.

http://www.collaborativefund.com/blog/immeasurably-important

Found at Josh Brown Reformed Broker https://www.linkedin.com/in/joshua-brown-96a5569b/

10. Ten Bad Habits That Are Killing Your Credibility

1. Interrupting people, or not listening to them while they speak but bursting in at the first opportunity after they’ve spoken, in order to share your opinion. If you have this bad habit, practice consciously listening to your conversational partner and then asking them, “Would you like to say more about that?” before sharing your own thoughts.

2. Failing to use “Please” and “Thank you” in your interactions with your teammates, your manager, customers and vendors and everyone else you interact with at work.

3. Leaving details to the last minute so that you have to run around averting a crisis instead of planning ahead.

4. Being a suck-up to the boss, spying on your coworkers and reporting back to your manager or sharing one set of opinions with your teammates and a completely different set with your boss.

5. Using “uptalk” — speech that ends every sentence with an ascending inflection, like a question. Here’s what uptalk sounds like:

You: So, I have to finish this report by Friday? I have to get it to the VP so he can put the pricing plan together? That’s why I asked you to meet with me, so we can go over it before I present it to the VP? If we can just go through it quickly that will be great? I really appreciate your time?

6. Making a point of staying later at the office than everyone else and arriving earlier in the morning than anyone else does. Effective employees get their work done during the work day. You will never become more credible by working longer hours to show the boss how dedicated you are.

7. Forgetting to write down details and note appointments and commitments in your calendar.

8. Taking credit for your coworkers’ ideas and accomplishments.

9. Gossiping.

10. Conducting loud, personal phone conversations in earshot of your teammates. Nobody wants to hear you arguing with your sweetheart or booking your spa treatments. Save those calls for a time when you’re outside the building, or use text instead of voice.

We don’t always know when we are irritating the people around us. Brenda did you a favor when she pointed out how your over-apologizing habit may be holding you back.

Now you have a project to dive into. Take Brenda’s coaching seriously and begin to notice when you’re tempted to apologize although there is nothing to apologize for — and you will overcome this small hurdle in no time!

The way to break any bad habit is to follow these three steps:

- Start by paying attention to the times when your bad habit shows up. Try to notice every time you fall into the rut and repeat your bad habit. Ask your friends at work to pay attention and remind you when you’re apologizing for nothing.

- As you become aware of the times and places where your bad habit typically emerges, prepare for those situations in advance. Prepare for someone to ask you, “Do you think you’ll have that report ready by Friday?” Practice a response that doesn’t involve an apology, like this one: “Friday sounds perfect — you’ll have the report then.”

- Acknowledge yourself whenever you make it through a day without repeating your bad habit, and give yourself a break when you slip back into the habit. It takes time to train yourself out of a bad habit and into a new, better one.

Be sure and let Brenda know that you’re taking her feedback to heart and that you appreciate it. Tell her that you’re working on the over-apologizing thing and you are grateful for her support.

Apologizing constantly is not the only bad habit that many people bring to work. Here are nine other habits that can kill your professional credibility:

All the best,

Liz

Liz Ryan is CEO/founder of Human Workplace and author of Reinvention Roadmap. Follow her on Twitter and read Forbes columns. Liz’s book Reinvention Roadmap is here.