1.Japan Still 15% Below Highs…Lagging in World Equities Rally

Japan ETF bounced just above 2016 lows.

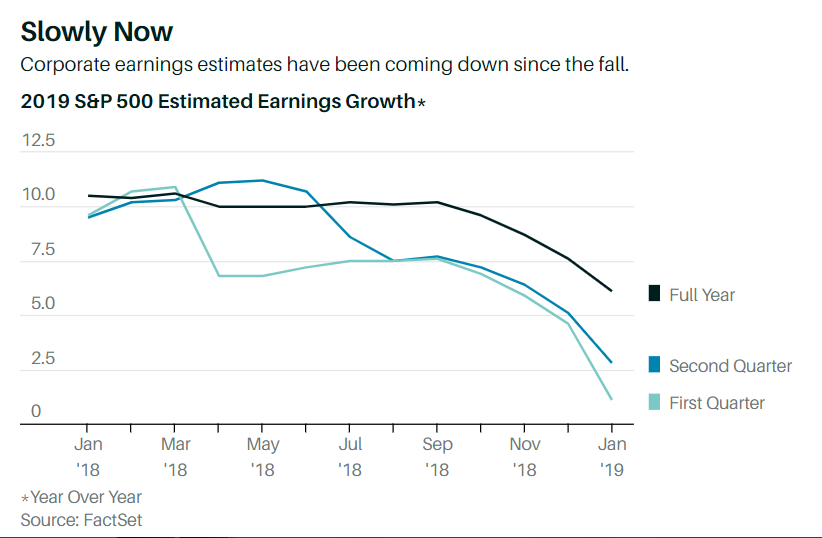

2.Record Positive Reaction to Earnings Shown in Yesterday’s Top 10…..Estimates Keep Coming Down…

How to Outsmart a Dimming Outlook for Profits

https://www.barrons.com/articles/how-to-outsmart-a-dimming-outlook-for-profits-51549070391

ByJack Hough

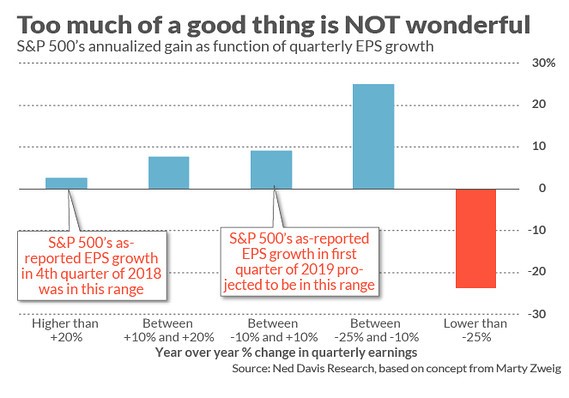

3.Opinion: Investors are interpreting the dramatic slowdown in corporate earnings all wrong

By Mark Hulbert

Faster earnings growth isn’t automatically better for the stock market

Getty Images

CHAPEL HILL, N.C. — Earnings growth has slowed dramatically, and—believe it or not—that’s good news.

That’s because the stock market typically performs the best when EPS growth rates are in the low single digits (percentage-wise) or even negative. In contrast, the stock market over the last century has tended to struggle whenever earnings growing rates were at or near record levels—like they were last year.

To contrarians, of course, this is not a new insight.

But, for the rest of us, it’s especially worth remembering now, given that this week marks the high point of the current quarter’s earnings season. Naive investors are hoping for faster earnings growth, without realizing that such growth doesn’t automatically or even usually translate into a higher stock market.

Take a look at the accompanying chart, which reflects data from Ned Davis Research. Since 1927, the stock market has performed the best in those quarters in which the S&P 500’sSPX, +0.68% earnings per share were between 10% and 25% lower than where they stood one year previously. In such quarters, the S&P 500’s average annualized return was 25.0%.

When year-over-year earnings growth was above 20%, in contrast, the S&P 500 gained an average of just 2.6% annualized.

These results help to explain why the stock market struggled for much of 2018, and why it has performed much better recently. The S&P 500’s EPS grew at a year-over-year rate above 30% in the fourth quarter of last year, a rate that falls within the range corresponding to the market rising at an annualized rate of just 2.6%. For the current quarter, in contrast, earnings are projected to grow at a year-over-year rate of 5%, which corresponds to an annualized gain of nearly 10% for the S&P 500—almost four times greater.

Why would the stock market do better when earnings are growing more slowly or actually falling? A big part of the explanation is that exceptionally fast earnings growth puts pressure on the Federal Reserve to raise interest rates and tighten monetary policy—which, in turn, is bad for stocks.

Sure enough, that’s just what we’ve seen. In the fourth quarter of 2018, when year-over-year earnings were growing at a blistering pace, the Fed stubbornly insisted on an aggressive schedule of rate increases in 2019—and the stock market struggled. So far in 2019, in contrast, as earnings growth rates have slowed considerably, the Fed has backed off its aggressive schedule—and the stock market has soared.

To be sure, there’s a limit to how much Wall Street will celebrate in the wake of an earnings recession. As you can see from the chart, the stock market typically plunges when earnings on a year-over-year basis fall by more than 25%. But only 7% of quarters since 1927 have experienced such a big decline in earnings. For the other 93% of the quarters, there is an inverse correlation between earnings growth and stock market appreciation.

Bear this in mind as you digest companies’ quarterly earnings reports this week. Don’t automatically be upset if the average company’s guidance is for only mediocre earnings growth in 2019.

For more information, including descriptions of the Hulbert Sentiment Indices, go to The Hulbert Financial Digest or email mark@hulbertratings.com.

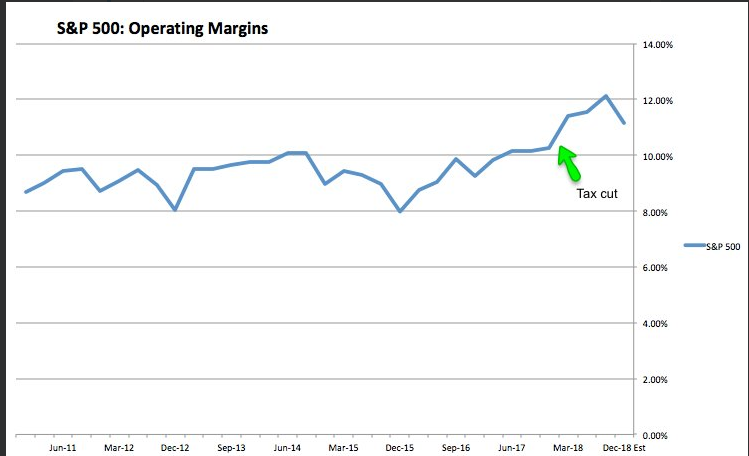

4. Margins drop from 12.1% to 11.1% as one-time tax cut boost fades

Urban Carmel

https://twitter.com/ukarlewitz

5.Volatility Lower But Still Above First 3 Quarters of 2018 Range.

6.Top of Everyone’s Radar is Fed’s Balance Sheet…Opinion Below.

Stop Worrying About the Fed’s Balance Sheet

It’s not the threat that people seem to think it is.

By

Bill Dudley

Bill Dudley is a senior research scholar at Princeton University’s Center for Economic Policy Studies. He served as president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York from 2009 to 2018, and as vice chairman of the Federal Open Market Committee. He was previously chief U.S. economist at Goldman Sachs.

Financial types have long had a preoccupation: What will the Federal Reserve do with all the fixed income securities it purchased to help the U.S. economy recover from the last recession? The Fed’s efforts to shrink its holdings have been blamed for various ills, including December’s stock-market swoon. And any new nuance of policy — such as last week’s statement on “balance sheet normalization” — is seen as a really big deal.

I’m amazed and baffled by this. It gets much more attention than it deserves.

Let’s start with the stock market. Yes, it’s true that stock prices declined at a time when the Fed was allowing its holdings of Treasury and mortgage-backed securities to run off at a rate of up to $50 billion a month. But the balance sheet contraction had been underway for more than a year, without any modifications or mid-course corrections. Thus, this should have been fully discounted.

Moreover, if anything, the run-off of the Fed’s balance sheet had a smaller-than-expected impact on the yields of those securities. Longer-term Treasury yields remained low, and the spread between them and the yields on agency mortgage-backed securities didn’t change much. It’s hard to see how the normalization of the Fed’s balance sheet tightened financial conditions in a way that would have weighed significantly on stock prices.

Better explanations for this fall’s weakness in the equity market abound. For one, economic growth and corporate profits looked set to falter in 2019, as the effects of corporate tax cuts waned and the labor market tightened. Demand for scarce labor should increase its share of income, crimping profits. And if the economy didn’t slow enough on its own, the Fed was likely to raise interest rates to make sure that happened. These developments weren’t good for an equity market that had been accustomed to strong earnings growth and an accommodative central bank.

Why then, one might ask, did the Fed announce changes to its plans to pare down its holdings of Treasury and mortgage-backed securities? Actually, there wasn’t much of a change at all. Here’s what Chairman Jay Powell said at his news conference last week:

- The Fed will maintain a balance sheet big enough to satisfy banks’ demand for reserves, with a buffer above that so the Fed will not have to intervene in the money markets on a day-to-day basis;

- The Fed now expects banks to demand more reserves than previously thought, so its balance sheet will likely be larger — this means more securities in its portfolio;

- The Fed could use its balance sheet more actively as a monetary policy tool but only if interest-rate adjustments — its primary tool — were to prove inadequate.

None of this should be a surprise. It always was likely that the Fed would maintain the current “floor” system, in which its choice of the interest rate it pays on reserves drives monetary policy. It also has been clear that banks would have a greater demand for reserves than in prior expansions. That’s because the central bank now pays interest on those reserves, and post-crisis regulations require banks to keep a lot more cash and other liquid assets on hand.

The new news here is simply that Fed sees greater demand for reserves than it expected a year ago. But even this should not be a big surprise. After all, the federal funds rate — the interest rate that banks pay to borrow reserves from one another — had crept up to equal the rate that the Fed itself pays on reserves. So the central bank’s conclusion is just consistent with what we have already seen happening in money markets.

The concept of using the balance sheet as a monetary-policy tool isn’t new, either. It has always been part of the Fed’s toolkit. The shift is merely in emphasis. When the Fed was clearly on a tightening path, the attention was on interest rates. The Fed has made it clear that this is the primary tool of monetary policy and that hasn’t changed a whit. However, now that the balance sheet is getting more attention and the direction of short-term interest rates is less certain, the Fed is simply reminding people that the balance sheet is still available in circumstances where its primary tool might be insufficient.

We are nowhere close to that situation today. The balance sheet tool becomes relevant only if the economy falters badly and the Fed needs more ammunition.

It’s worth pointing out that the composition of the balance sheet is also important. Not only does it matter how much the Fed holds in Treasury and mortgage-backed securities, but also — for Treasury securities — whether they are predominately short-term bills, medium-term notes or long-term bonds.

On this score, the Fed faces several important decisions. First, once the balance sheet gets to the desired size, what will it do with its still-large holdings of mortgage-backed securities? Will it just let them run off passively, or more actively sell them off? Under a passive approach, it would take several decades for the holdings to disappear.

Second, on the Treasury side, what should the composition be? Before the crisis, the Fed held Treasury securities across the maturity spectrum. Now, with a much bigger balance sheet, there is more reason to shift to Treasury bills. Holding mostly bills would reduce exposure to interest rate risk and increase the firepower available to fight future economic downturns. Should quantitative easing be needed, the Fed would have greater scope to extend the maturities of its holdings, not just increase the size of its balance sheet.

The bottom line: The Fed’s balance sheet isn’t the threat that market participants sometimes make it out to be, and last week’s announcements do not have significant implications for the interest rate outlook. Market participants would be better off focusing on the economic outlook. This is what will drive monetary policy and the Fed’s decisions about the appropriate trajectory for short-term interest rates over the next year. If the outlook changes, so will the Fed’s thinking.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

To contact the author of this story:

Bill Dudley at wcdudley53@gmail.com

https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2019-02-05/stop-worrying-about-the-fed-s-balance-sheet

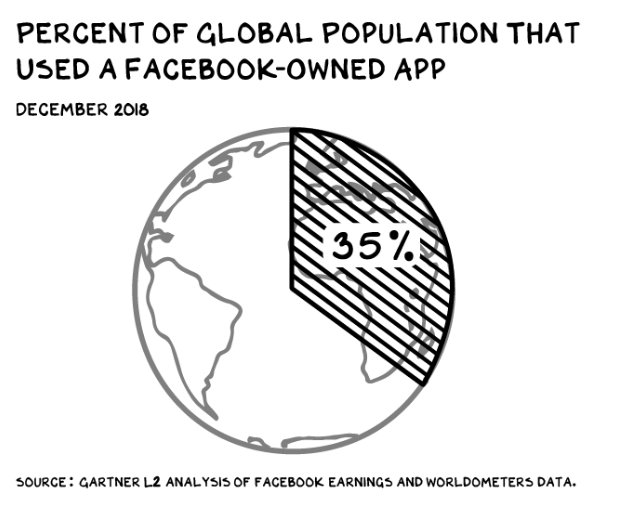

7.Facebook 35% of World Population.

What Were You Doing at Age 15?

Facebook turns 15 years old today. And really, it’s just like any other teenager—suffering through growing pains, being scolded by authority figures, and serving as a platform for 35% of the world’s population.

Via Gartner L2

https://www.morningbrew.com/

8.Integrity is by far the most important attribute of a leader.

Brigette Hyacinth

Author: The Future of Leadership: Rise ofAutomation, Robotics and Artificial I… See more

Society longs for leaders of integrity. Sadly what we often see is a greed, selfishness and a lust for power. Integrity is something that is built over time, not overnight. It can take years to build and be destroyed in one moment. Once trust is lost, it is hard to regain.

7 Deal-breaking behaviours that makes employees lose trust in their leaders.

- Taking credit for someone’s work.

- Blaming others and not standing up for your team.

- False promises to get someone to do something.

- Favoritism and being unfair.

- Downplaying employees’ accomplishments to make oneself look better.

- Not appreciating loyalty, hard-work and efforts of others.

- Treating others poorly – not showing respect or empathy, micromanaging employees, not trusting them to do their job.

Train people well enough so they can leave. Treat them well enough so they don’t want to. -Richard Branson

People don’t leave bad jobs. They leave bad bosses. A lot of business leaders don’t even realize how closely they’re being watched by their subordinates. Your ability to influence is not just based on skill or intelligence; it’s based on trust and requires integrity, which is the foundation of real and lasting influence.

Leadership is about people. Your business is nothing more than the collective energy and efforts of the people working with and for you. An employee’s relationship with their manager sets the tone for their level of commitment to the organization’s success. Threats and intimidation only yield temporary results. You can’t keep throwing your employees under the bus and expect them to give their all.

If you are not a person of integrity— your team won’t trust you, vendors don’t believe you, and customers will not support your business.

People might tolerate a boring job or long commute, but they are more prone to leave if their boss treats them poorly. Many companies are struggling with low employee engagement. It all comes down to how you treat people. For loyalty, there has to be a relationship that develops between employee and employer and this develops over time through trust that gets built and sustained. Transparency, authenticity and walking the talk are essential for building trust. You can’t buy loyalty, but you can certainly foster and nurture it by being a person of integrity.

https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/integrity-far-most-important-attribute-leader-brigette-hyacinth/