1. 3Q Summary-Large Growth and Consumer Discretionary Lead.

LPL BLOG

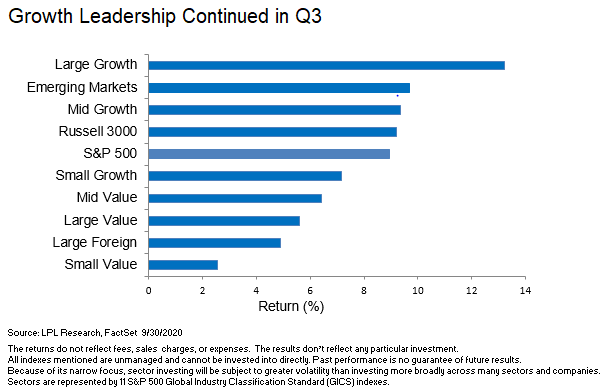

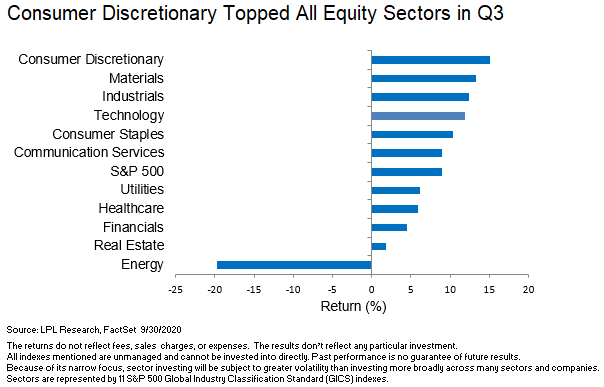

Growth beat value for the quarter despite losing ground in September. The growth style of investing continued its impressive 2020 run during the quarter, shown in the LPL Chart of the Day, but underperformed during September as markets pulled back and rotated some from the winners to the laggards. Value’s outperformance for the month was its first such feat in 12 months, based on the Russell 1000 style indexes. Over the full quarter, growth got a boost from strong gains in technology, while value was hurt by weakness in the energy sector.

Consumer discretionary topped all equity sectors for the quarter. Gains were broad-based, though homebuilders stood out with outsized gains as the housing market remains quite strong. The internet retailers lagged slightly behind the sector as some of the pandemic winners took a breather late in the quarter. Energy struggled mightily with a nearly 20% decline even though oil and natural gas prices rose, bringing the sector’s 2020 loss to 48% through September 30.

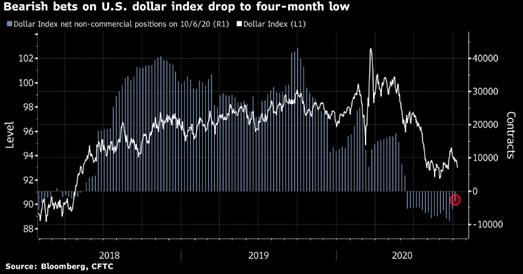

2. Hedge Funds Cut Bearish Dollar Bets to Least in 4 Months

Dollar bears are dialing back on their aggressive bets for further weakness. Net short non-commercial positions in futures linked to the ICE US Dollar Index have been cut to the least in four months. – CFTC

Chris Preston -River and Mercantile.

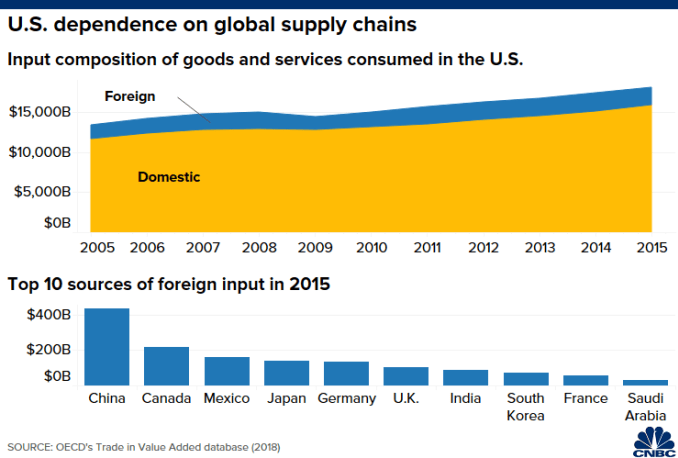

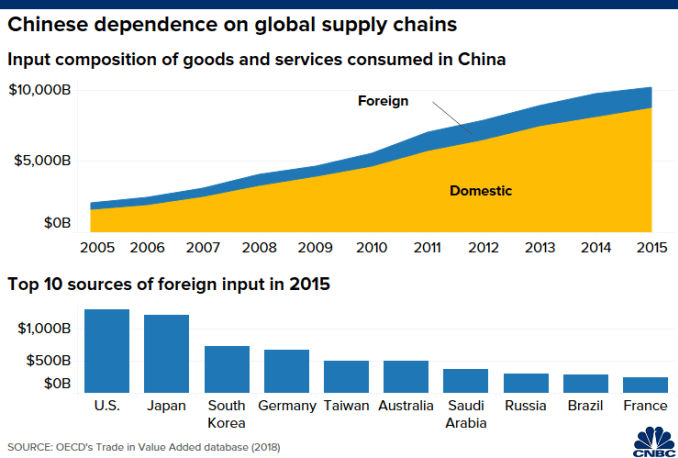

3. Rising Supply Chain Linkages Between U.S. and China.

Supply chain linkages

Beyond direct trade, the U.S. and China have also become “increasingly interdependent through rising supply-chain linkages over the past decade,” Fitch Ratings said in a report last month.

Supply chains are a complex network of companies that work together to provide raw materials, intermediate parts or expertise in order to produce a final product or service that can be consumed either domestically or globally.

It’s hard to gather accurate data that breaks down specific supply chain contributions by each company. However, the OECD — or the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development — launched a database in 2013 that provides some insight into how global supply chains work.

Latest available estimates by the OECD showed that in 2015, foreign input accounted for 12.2% — or around $2.2 trillion — of total goods and services consumed in the U.S. China was the largest contributing country of that foreign input, the data showed.

Some manufacturers within the U.S. were especially reliant on China for intermediate input or final products, said Fitch, citing the OECD data. Those include American producers of textiles, electronics, basic metals and machinery, the agency said.

In China, foreign suppliers made up around 14.2%, or $1.4 trillion, of total goods and services consumed within its borders in 2015, according to OECD data. The U.S. was also the largest single contributing country to that foreign input, the estimates showed.

In contrast with U.S. reliance on Chinese input in the manufacturing sector, China is “much more” dependent on American contribution in services, said Fitch.

5 charts show how much the U.S. and Chinese economies depend on each other

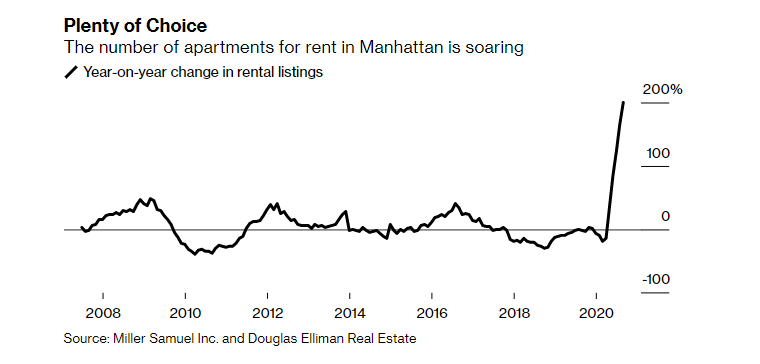

4. The Number of Apartments in Manhattan for Rent +200%

Rent or Buy? Eight Home Hunters Explain Their Real Estate Moves During Covid-From New York to Sydney, the fallout from the pandemic has changed the calculus for those searching for a house.By Jack Pitcher-Emily Cadman-Oshrat Carmiel-Julia Fanzeres-Kristine Aquino

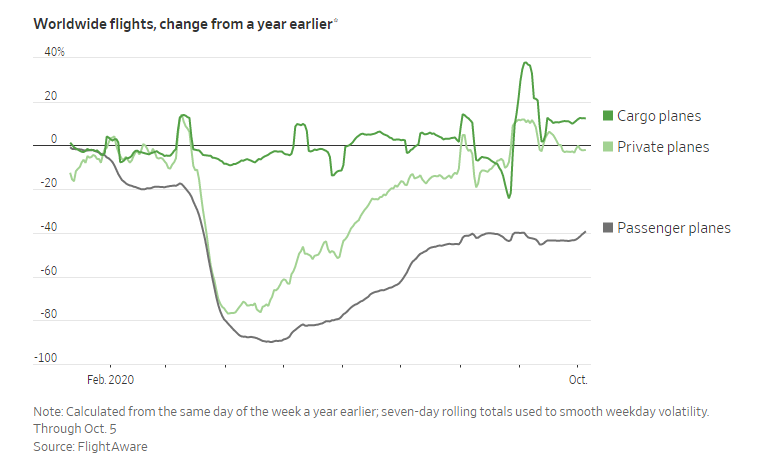

5. Cargo Planes and Private Planes Back to Flat…..Passenger Planes -40%

WSJ

The Oil Market Has an Aviation Problem-Passenger-flight activity is mired at around half of pre-pandemic levels, leaving a hole in global oil demand

https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-oil-market-has-an-aviation-problem-11602235754?mod=itp_wsj&ru=yahoo

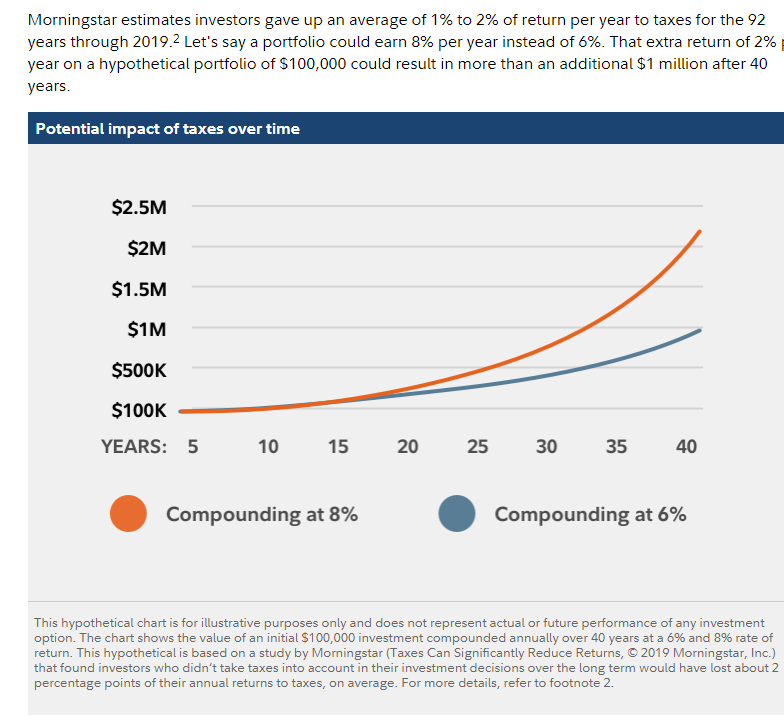

6. Taxes Compound Like Returns.

Fidelity

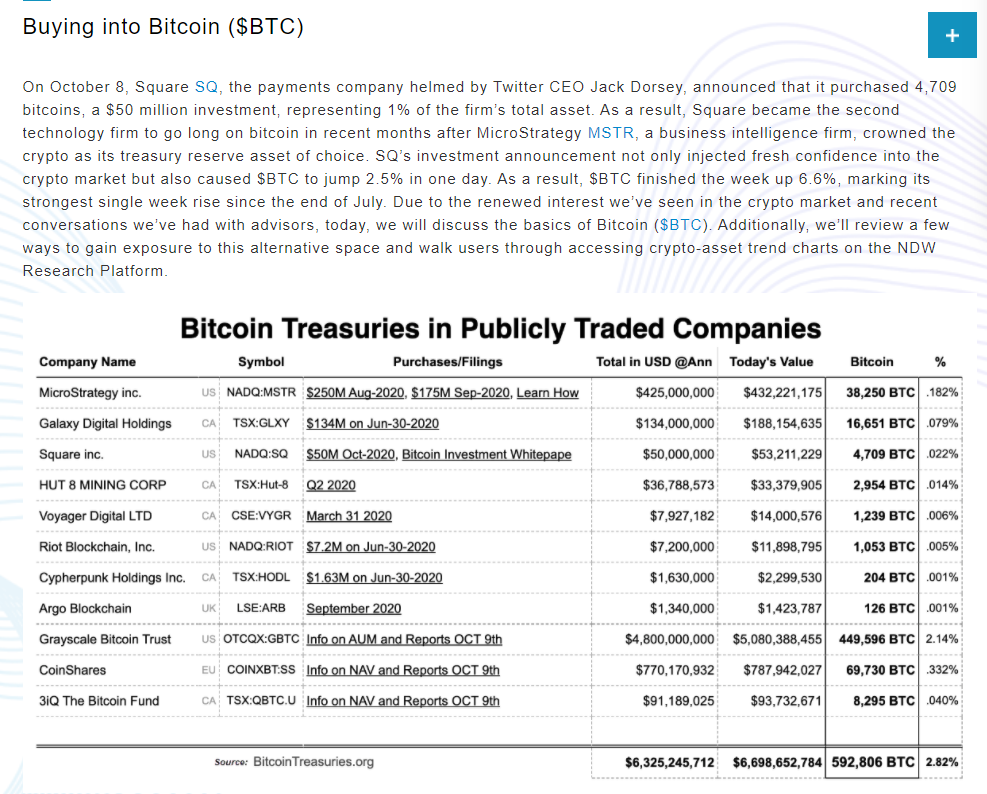

7. Public Companies Who Hold Bitcoin as Asset

From Nasdaq Dorsey Wright

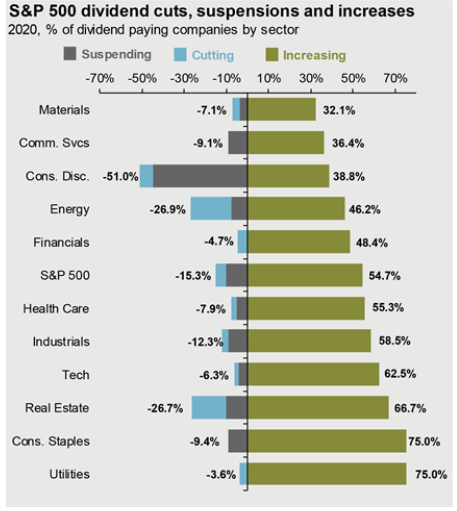

8. Summary of S&P Dividend Cuts, Suspensions, And Increases.

JP Morgan Asset

https://am.jpmorgan.com/us/en/asset-management/gim/per/insights/guide-to-the-markets/viewer

9. The huge return on investing in coronavirus tests

Felix Salmon, author of Capital

Government spending on testingand contact tracing pays for itself more than 30 times over, according to a new paper published by the American Medical Association.

What they found: Harvard economists David Cutler and Lawrence Summers (yes, that Larry Summers) calculated the total cost of the coronavirus pandemic at more than $16 trillion in the United States alone. Of that, about $7 trillion is attributable to loss of life and long-term impairment from the disease.

- Enhanced testing and tracing would cost about $6 million per 100,000 inhabitants, they calculate. Out of that population, 14 lives would be saved, on which they place a value of $96 million, and 33 critical and severe cases would be avoided, representing savings of $80 million.

- That adds up to $176 million in benefits from $6 million in costs — before taking into account any second-order effects from even fewer cases down the road.

The bottom line: “Currently, the U.S. prioritizes spending on acute treatment,” write Cutler and Summers, “with far less spending on public health services and infrastructure.”

- Going forward, they write, “a minimum of 5% of any COVID economic relief intervention should be devoted to such health measures.”

https://www.axios.com/coronavirus-testing-investment-eca1e901-8cbe-4015-b77a-594e4dc6c16d.html

10. What Makes Some People More Productive Than Others

Would you rate yourself as highly productive?

We’ve learned a lot about personal productivity and what makes some people more productive than others. Last year we published a survey to help professionals assess their own personal productivity — defined as the habits closely associated with accomplishing more each day. The survey focused on seven habits: developing daily routines, planning your schedule, coping with messages, getting a lot done, running effective meetings, honing communication skills, and delegating tasks to others.

After cleaning up the data, we obtained a complete set of answers from 19,957 respondents across six continents. Roughly half were residents of North America; another 21% were residents of Europe and 19% were residents of Asia. The remaining 10% was comprised of residents (in descending order) from Australia, South America, and Africa.

Our survey had its limits — for example, respondents were a self-selected sample of readers of HBR.org, and the ratings were self-assessments of habits rather than objective measures of people’s productivity. Nevertheless, we believe the survey results provide useful insights into important productivity habits and challenges facing professionals.

Three general patterns stood out: First, working longer hours does not necessarily mean higher personal productivity. Working smarter is the key to accomplishing more of your top priorities each day. Second, age and seniority were highly correlated with personal productivity — older and more senior professionals recorded higher scores than younger and more junior colleagues. Third, the overall productivity scores of male and female professionals were almost the same, but there were gender differences on particular habits that promote personal productivity.

More specifically, we found that professionals with the highest productivity scores tended to do well on the same clusters of habits. They planned their work based on their top priorities, and then acted with a definite objective. They developed effective techniques for managing a high volume of information and tasks. And they understood the needs of their colleagues — for short meetings, responsive communications, and clear directions.

Let’s go deeper into the survey results. On geography, the average productivity score for respondents from North America was in the middle of the pack, even though Americans tend to work longer hours. The North American score was significantly lower than the average productivity scores for respondents from Europe, Asia, and Australia. On the other hand, the North American score was significantly higher than the average productivity scores for residents of South America and Africa (though recall these were the areas where we had the least data).

Drilling down into the data, we found the higher productivity scores for Europe, Asia, and Australia were driven by strong habits in areas such as daily schedules, not constantly checking messages, focusing early on the final product, and thinking carefully before reading or writing.

While our survey turned up significant differences in productivity scores by continent, it showed minimal differences between the average scores of male and female respondents. Overall, the respondents were 55% male and 45% female.

Yet there were some noteworthy differences in how women and men managed to be so productive. Women tended to score particularly high when it came to running effective meetings — women were more likely than men to send out an agenda in advance, keep meetings to less than 90 minutes, and finish meetings with an agreement on next steps. Women were also more likely to say that they prepared their calendars the night before and responded promptly to important emails.

By contrast, men did particularly well when it came to coping with high message volume — not looking at their emails too frequently and skipping over the messages of low value. Men were also more likely than women to report keeping free slots in their daily schedules, getting quickly to the final product, and composing outlines before writing memos.

Beside geography and gender, we analyzed the responses to our questionnaire by age and seniority. There were five age brackets — with the most respondents in the under-30 bracket and the least in the over-60 bracket. We found that the productivity scores of respondents rose systematically the older they got. This trend seems to reflect the benefits of learning from years of experience how to work smarter. The drivers of these higher productivity scores for respondents in older age brackets were their stronger habits in four areas: developing routines for low-value activities, managing message flow, running effective meetings, and delegating tasks to others.

The story was somewhat similar when it came to seniority. There were five levels of seniority captured in the data, with 5 being the most junior and 1 being the most senior. The number of respondents was highest in the most junior level and lowest at the most senior level. As with age, the productivity scores rose systematically with successively higher levels of seniority. This may suggest that business professionals attain higher levels of seniority in part by cultivating good productivity habits (or vice versa, people become more senior and then have to become more productive). However, the drivers of higher scores for senior level respondents were different than those for older respondents. More senior respondents achieved high productivity from better planning of their schedules, getting a lot done, and stronger communication skills.

Finally, we focused on the tails in each of the four demographic categories. We defined tails to include all respondents whose total score fell outside of two standard deviations from the mean. The left tail comprised those with the lowest scores; the right tail had the highest scores. We didn’t find any geographic or gender patterns on either tail, though we saw a few of the youngest and most junior professionals in the right tail with the highest scores.

The professionals in the right tail with the highest productivity scores were particularly adept at overcoming procrastination, getting to the final product, and focusing on daily accomplishments. Low ratings on these three habits were typically reported by professionals with the lowest productivity scores. In addition, professionals in the right tail were much better at advance planning — reviewing schedules the night before, sending out meeting agendas, and setting success metrics for their teams. Professionals in the left tail had low scores on these aspects of advance planning. They also did not leave open slots in their schedules and did not use outlines before writing memos.

So what should professionals take away from the results of our survey? If you want to become more productive, you should develop an array of specific habits.

First, plan your work based on your top priorities, and then act with a definite objective.

· Revise your daily schedule the night before to emphasize your priorities. Next to each appointment on your calendar, jot down your objectives for it.

· Send out a detailed agenda to all participants in advance of any meeting.

· When embarking on large projects, sketch out preliminary conclusions as soon as possible.

· Before reading any length material, identify your specific purpose for it.

· Before writing anything of length, compose an outline with a logical order to help you stay on track.

Second, develop effective techniques for managing the overload of information and tasks.

· Make daily processes, like getting dressed or eating breakfast, into routines so you don’t spend time thinking about them.

· Leave time in your daily schedule to deal with emergencies and unplanned events.

· Check the screens on your devices once per hour, instead of every few minutes.

· Skip over the majority of your messages by looking at the subject and sender.

· Break large projects into pieces and reward yourself for completing each piece.

· Delegate to others, if feasible, tasks that do not further your top priorities.

Third, understand the needs of your colleagues for short meetings, responsive communications, and clear directions.

· Limit the time for any meeting to 90 minutes at most, but preferably less. End every meeting by delineating the next steps and responsibility for those steps.

· Respond right away to messages from people who are important to you.

· To capture an audience’s attention, speak from a few notes, rather than reading a prepared text.

· Establish clear objectives and success metrics for any team efforts.

· To improve your team’s performance, institute procedures to prevent future mistakes, instead of playing the blame game.

A former President of Fidelity Investments, Robert C. Pozen is a senior lecturer at MIT’s Sloan School of Management in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and a nonresident senior fellow at the Brookings Institution.

Kevin Downey is a student at MIT.