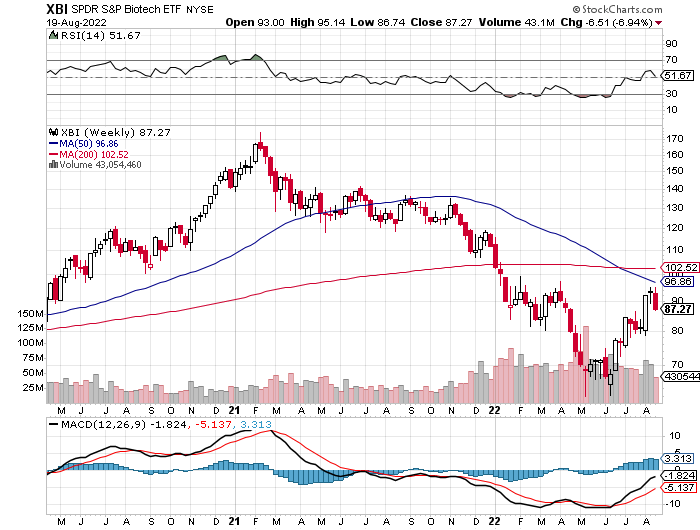

1. XBI Biotech ETF Rallied 40% Since June

XBI big rally but fails below 200day

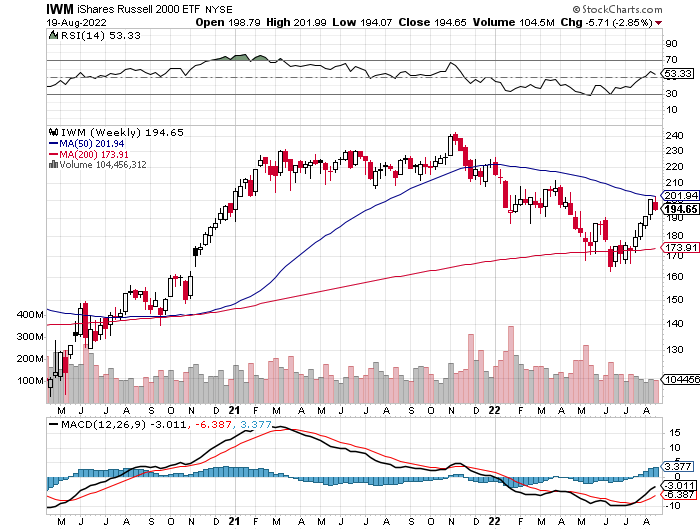

2. Small Cap Russell 2000 Rallies 20% Since June

Small Cap held 200week moving average

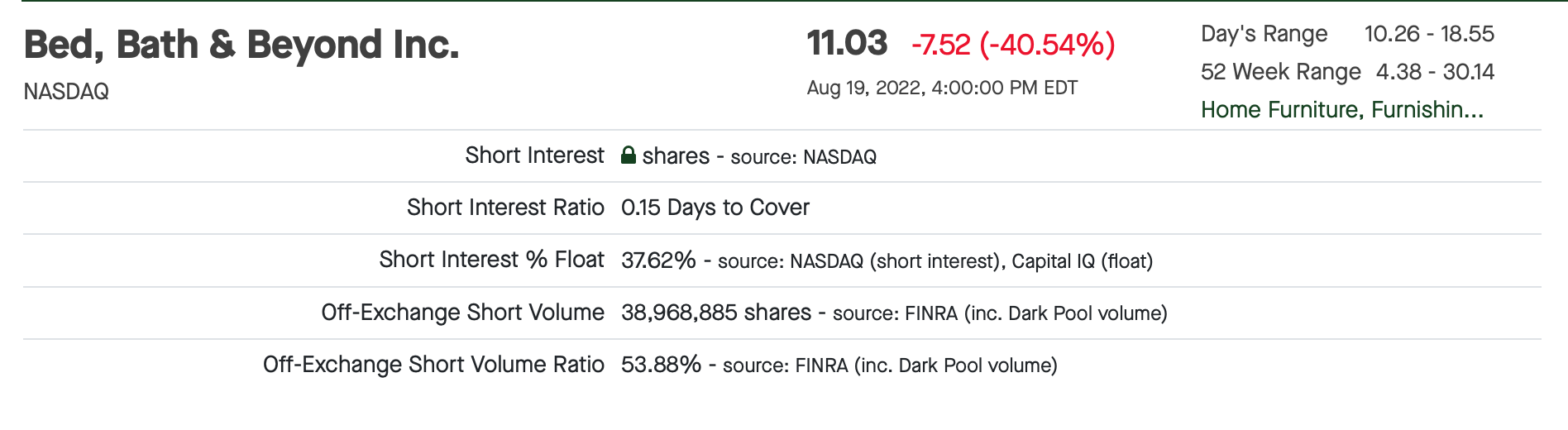

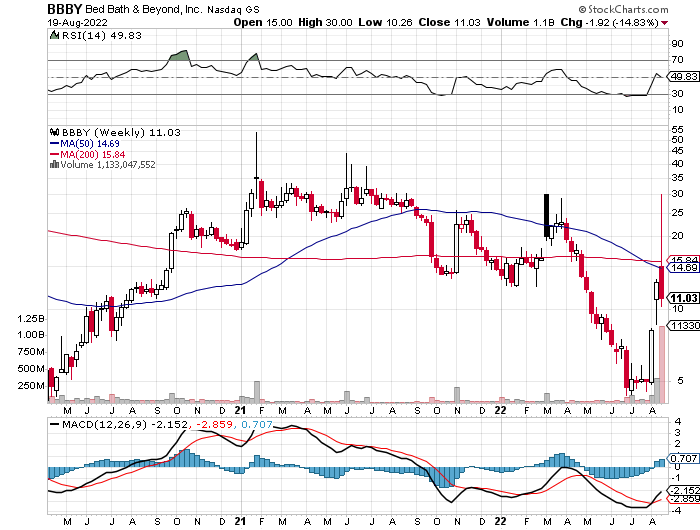

3. BBBY Short Interest Got to 55% of Float …Now 38%

https://fintel.io/ss/us/bbby

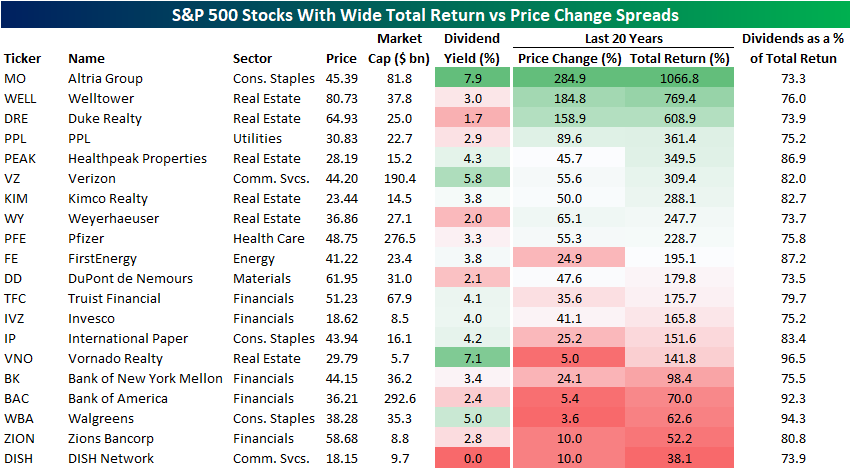

4. S&P Stocks with 80% of Returns Coming from Dividends

Bespoke Investment Group-The table below outlines twenty S&P 500 stocks that have seen a high percentage of their returns over the last twenty years come from dividends. The average stock on this list has seen over 80% of their gains over the last two decades come from dividends alone. Although the average stock on this list has only seen a price gain of 61.1% since August of 2002, their average total return when factoring in dividends re-invested has been 278%.

https://www.bespokepremium.com/interactive/posts/think-big-blog/total-return-vs-price-change-spreads

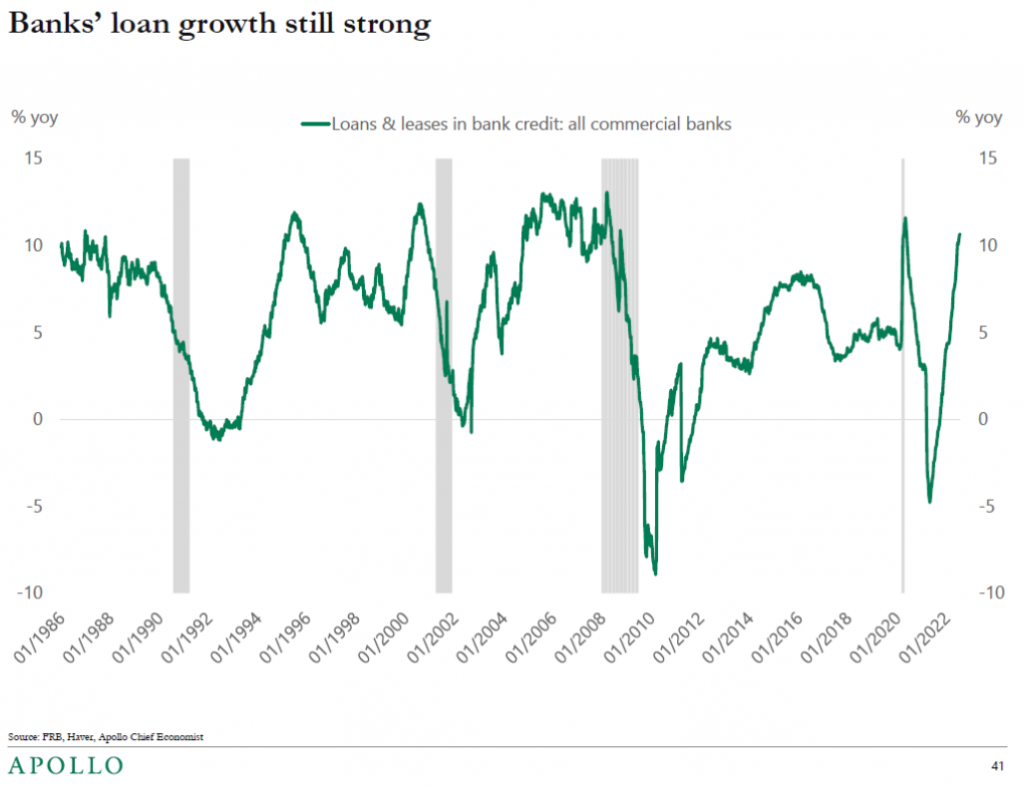

5. Bank Loans Still Growing

Bank Loan Growth From Torsten Slok’s “Recession Watch” chartpack today: If you are thinking we are currently in, or were recently in, a recession, this is a picture you should be contemplating.

Econbrowser https://econbrowser.com/

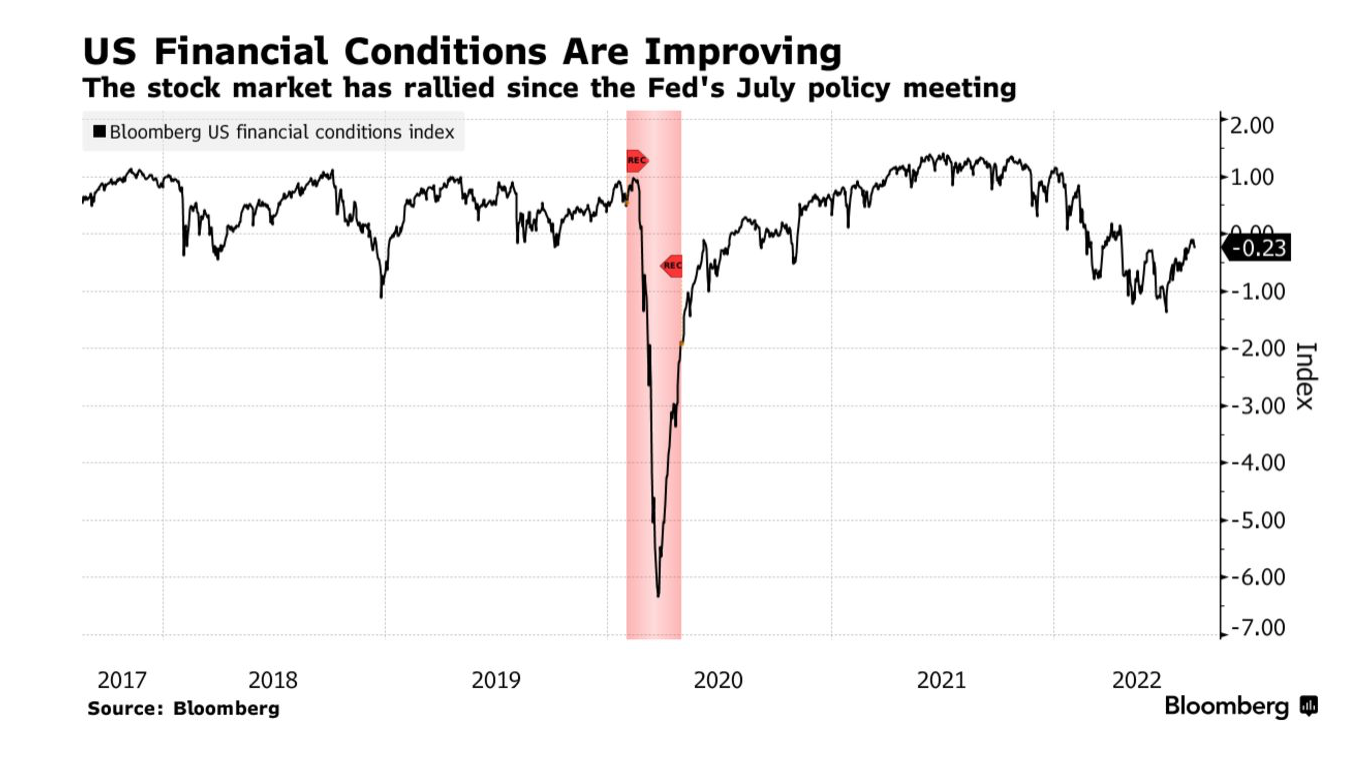

6. Bloomberg Financial Conditions Index Improving

Factors behind the BFCI include:

1. the US Ted spread (difference between Libor and Tbills rate)

2. the Libor/OIS spread (an important metric of whole sale liquidity availability measuring the difference between the Libor rate and the interest rate swap level of an equivalent tenor. Libor measures the cost of lending with exchange of principal while the swap rate (OIS) is “just” an interest rate level at which interest rate risk can be undertaken or hedged in the derivatives market without exchange of principal i.e. without actual lending of borrowing of money. During the 2007 crisis, it was possible to exchange interest rate risk …but not borrow money which led to a sharp increase in the Libor/OIS spread.

3. the commercial paper/T-bills spread (difference in credit spreads between corporate and government paper in the money market curve (1 to 12 months tenor). During the crisis, everybody rushed into T-bills with few interested by corporate credit risk (commercial paper) even and sometimes in particular in short term maturities.

4. US High Yield /10Y Treasury spread measuring the long term credit spread between US treasuries and US High yield.

5. US Muni/10Y Treasury spread measuring the long term credit premium between US municipal bonds and US treasuries

6. Swaption Volatility index

7. S&P500 (stock market level)

8. VIX (Spot Option volatility on the S&P500)

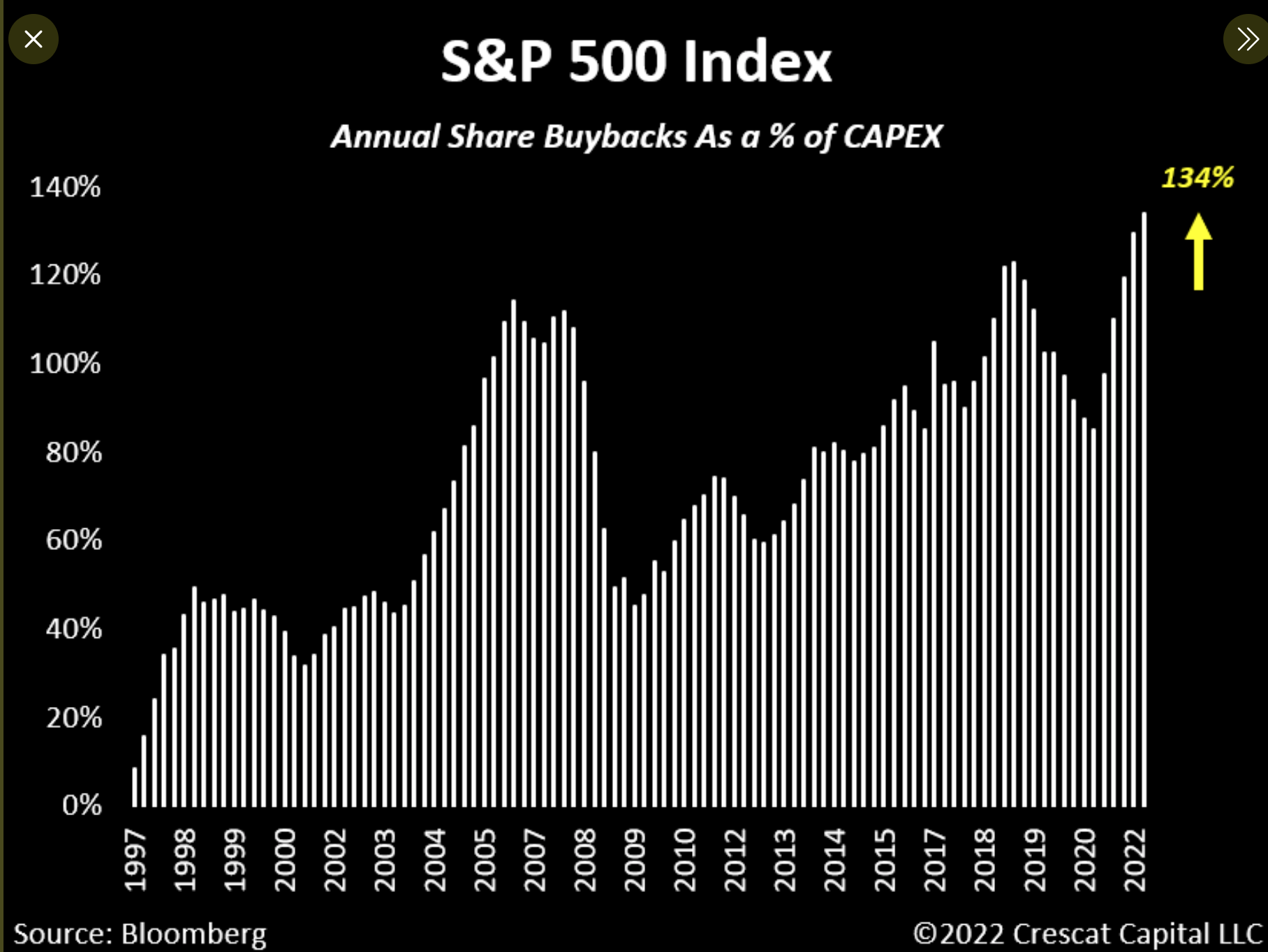

7. Buyback Tax in New Bill….S&P Buybacks 25 Year High vs. CAPEX.

@tavicosta Companies are doing more share buybacks versus investing in their own businesses than any other time in the last 25 years.

https://twitter.com/TaviCosta

8. Three Arrows Capital-The Crypto Geniuses Who Vaporized $1 Trillion

Trillion Dollar

New York Mag-Among crypto’s smartest observers, there is a widely held view that Three Arrows is meaningfully responsible for the larger crypto crash of 2022, as market chaos and forced selling sent bitcoin and other digital assets plunging 70 percent or more, erasing more than a trillion dollars in value. “I suspect they might be 80 percent of the total original contagion,” says Sam Bankman-Fried, who as CEO of FTX, a major crypto exchange that has bailed out some of the bankrupt lenders, has perhaps more visibility on the problems than anyone. “They weren’t the only people who blew out, but they did it way bigger than anyone else did. And they had way more trust from the ecosystem prior to that.”

For a firm that had always portrayed itself as playing just with its own money — “We don’t have any external investors,” Zhu, 3AC’s CEO, had told Bloomberg as recently as February — the damage Three Arrows caused was astonishing. By mid-July, creditors had come forward with more than $2.8 billion in claims; the figure is expected to balloon from there. Everyone in crypto, from the largest lenders to wealthy investors, seemed to have lent 3AC their digital coins, even 3AC’s own employees, who deposited their salaries with its “borrowing desk” in exchange for interest. “So many people feel disappointed and some of them embarrassed,” says Alex Svanevik, the CEO of Nansen, a Singapore-based blockchain-analytics company. “And they shouldn’t because a lot of people fell for this, and a lot of people gave them money.”

That money appears to be gone now, along with the assets of several affiliated funds and portions of the treasuries of various crypto projects 3AC had managed. The true scale of the losses may never be known; for many of the crypto start-ups that parked their money with the firm, disclosing that relationship publicly is to risk increased scrutiny from both their investors and government regulators. (For this reason, along with the legal complexities of being a creditor, many people who spoke about their experiences with 3AC have asked to remain anonymous.)

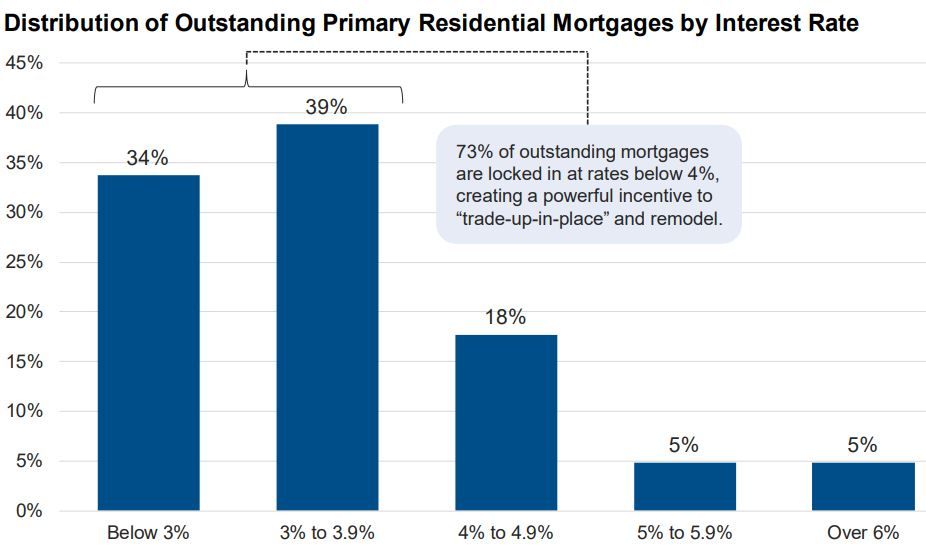

9. 73% of Homeowners Mortgages are Below 4%….They are not Moving.

John Burns Real Estate-73% of homeowner mortgages are less than 4%, which is a great reason to stay put.

I recently learned why those with high interest rates don’t refinance. They often have such a small remaining balance that it isn’t worth it for the lender to offer them a refi.

https://www.linkedin.com/in/johnburns7/

10. Stop drinking, keep reading, look after your hearing: a neurologist’s tips for fighting memory loss and Alzheimer’s

‘The art of memory is the art of attention’ …

When does forgetfulness become something more serious? And how can we delay or even prevent that change? We talk to brain expert Richard Restak

You walk into a room, but can’t remember what you came in for. Or you bump into an old acquaintance at work, and forget their name. Most of us have had momentary memory lapses like this, but in middle age they can start to feel more ominous. Do they make us look unprofessional, or past it? Could this even be a sign of impending dementia? The good news for the increasingly forgetful, however, is that not only can memory be improved with practice, but that it looks increasingly as if some cases of Alzheimer’s may be preventable too.

Neuroscientist Dr Richard Restak is a past president of the American Neuropsychiatric Association, who has lectured on the brain and behaviour everywhere from the Pentagon to Nasa, and written more than 20 books on the human brain. His latest, The Complete Guide to Memory: The Science of Strengthening Your Mind, homes in on the great unspoken fear that every time you can’t remember where you put your reading glasses, it’s a sign of impending doom. “In America today,” he writes “anyone over 50 lives in dread of the big A.” Memory lapses are, he writes, the single most common complaint over-55s raise with their doctors, even though much of what they describe turns out to be nothing to worry about.

Coming out of a shop and not being able to remember where you left the car, for example, is perfectly normal: it’s likely you just weren’t concentrating when you parked, and therefore the car’s location wasn’t properly encoded in your brain. Forgetting what you came into a room for is probably just a sign you’re busy and preoccupied with other things, says Restak.

“Samuel Johnson said that the art of memory is the art of attention,” he says, down the line from his office in Washington DC (at 80, Restak is still a practising clinical professor at George Washington Hospital University School of Medicine and Health). “Most of these sins of ‘memory loss’ are sins of not paying attention. If you’re at a party and you’re not really listening to someone, because you are still thinking about some work-related matter, suddenly later you find you can’t remember their name. The first thing is you put the information in memory – that’s consolidating it – and then you have to be able to retrieve it. But if you’ve never consolidated it in the first place, it doesn’t exist.”

But what if you forget where you left your car keys, and eventually find them inside the fridge? “That’s often the first sign of something serious – you open up the refrigerator door, and it’s the newspaper, or your car keys, inside. That’s a little bit beyond forgetful.”

Memory does vary, he points out, and some people will always have been scatty. But the real red flag is a change that seems out of character. If you’re a keen card player who prides yourself on always keeping track of which cards have been played, and suddenly realise you can’t do that any more, it could be worth investigating. Similarly, Restak has noticed that many patients in the early stages of dementia stop reading fiction, because it’s too difficult to remember what the character said or did a few chapters earlier – which is unfortunate, he says, because reading complex novels can be a valuable mental workout in itself.

Restak and his wife are currently on Alexandre Dumas’s The Count of Monte Cristo, which has a complex sprawling cast: “It’s an exercise in being able to keep track of characters without going backwards from one page to another.” If that’s already difficult for you, he says, it’s fine to underline the first mention of a new character and then flip back to remind yourself later if necessary. “Do whatever you have to, to keep yourself reading.”

Like following a recipe, keeping track of fictional plots is an exercise of working memory – as distinct from short-term memory (temporarily storing something like a phone number that you can safely forget the minute you’ve dialed it) or episodic memory, which covers things like recollections of childhood. Working memory is what we use to “work with the information we have”, says Restak, and it’s the one we should all prioritise. Left to its own devices, he points out, memory naturally starts to decline from your 30s onwards, which is why he advocates practising it daily.

Restak’s book is full of games, tricks and ideas for honing recall, often involving creating vivid visual images for things you want to remember. He holds a mental map of his neighbourhood in his head, incorporating visually familiar landmarks – his house, the local library, a restaurant he often goes to – and for each item on a list he wants to remember, he will create a memorable visual image and attach it somewhere specific on the map. To remember to buy milk, bread and coffee later, for example, he might envisage his house transformed into a carton of milk, the library full of loaves rather than books, and a giant cup of coffee spilling out of the restaurant.

The book also touches on broader lifestyle advice. Recently, research from the Lancet’s commission on dementia suggested up to 40% of Alzheimer’s cases could be prevented or delayed – much like heart disease and many cancers – by limiting 12 risk factors, from smoking to obesity and heavy drinking.

Restak advises his patients to quit alcohol by 70 at the latest. Over 65, he writes, you typically have fewer brain neurons than when you were younger, so why risk them? “Alcohol is a very, very weak neurotoxin – it’s not good for nerve cells.”

He’s also an advocate of the short afternoon nap, since getting enough sleep helps brain function (which may help explain why sleep-deprived new mothers, and menopausal women suffering from night sweats and insomnia, often complain of brain fog).

More unexpectedly, he recommends tackling hearing or vision problems promptly, because they make it harder to engage in conversations and hobbies that keep the cogs turning. “You have to have a certain level of vision to read comfortably, and if that’s missing then you are going to read less. As a result of that, you’re going to learn less and be a less interesting person to other people. All of these things really come down to socialisation, which is the most important part of keeping away Alzheimer’s and dementia, and keeping your memory.”

Socialisation is the most important part of keeping away Alzheimer’s and dementia, and keeping your memory

Is he saying that honing your memory can stop you getting Alzheimer’s? “No one can guarantee that anybody else is not going to get dementia. Take somebody like Iris Murdoch (the late writer, who suffered from it) – there’s probably not a more brilliant woman in all of Europe, so it shows that it can happen. But I compare it to driving a car: you can’t guarantee you won’t get in an accident but by wearing your seatbelt and checking your speed and keeping the car maintained, you can lessen your chances.”

Not all memories, however, are ones people want to treasure. Many have mental images they’d rather forget, whether it’s of an embarrassing mistake or a painful failed relationship, or intrusive flashbacks from post-traumatic stress disorder.

The fantasy of wiping the slate clean is a pervasive one in popular culture, from the film Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (about a couple who break up, and use a futuristic machine to zap memories of each other) to the Men in Black franchise, where alien-fighting secret agents electronically erase the memories of anyone who sees them in action, thus protecting mere mortals from the truth about what’s out there.

These may be strictly fantasies but we already have the technology, Restak suggests, to inhibit people from laying down memories that might in future haunt them. Beta blockers, drugs sometimes used to treat high blood pressure, have been found to dull the emotional response triggered when something frightening is recalled, but Restak says there’s evidence they also interfere with the consolidation of events as memories.

“There are actually discussions about whether these drugs should be part of the armoury that would be used if we have got to send people into terrible scenarios, such as after a shooting – that must be a horrible experience, to go in there and clean these places up.” But it’s a blunt tool – the drugs can’t distinguish between memories that might be useful in future to emergency first responders, and ones that are simply distressing – and raises complex questions about the ethics of tampering with people’s minds.

Don’t just look on dementia as a hopeless situation, although it’s a very frustrating one

Restak also highlights concerns about what he calls “memory wars”, or attempts to influence a nation’s collective memory by disputing what a particular event or period means. “The way we frame it in our memory is how we then perceive the world around us, and that’s what is encoded in the memory,” he says, pointing to recent political arguments in the US over whether the technical recession the country has entered – defined as two quarters of economic contraction – is actually a “real” recession. “It’s important because if you think you are in a recession you have certain beliefs and modes of action, and that’s how we are going to remember July 2022.”

And, as he argues, memory is intrinsic to who we are. It binds families and couples together, as we reminisce about our shared past. For individuals, meanwhile, past experience gives life meaning and texture. “We are what we can remember. The more things you can remember, the more clearly, the more full and enriched our personalities,” says Restak, who argues that the personalities of dementia sufferers can become flatter and more attenuated. “People say ‘Oh, they don’t seem to be the same person.’” Perhaps that’s why we fear Alzheimer’s so much: memory is so closely allied to a sense of self.

Yet even after memory loss has set in, it’s not necessarily too late to help people hold on to whatever’s left. One neurologist Restak knows had two patients who “weren’t sure where they were or what day it was”, but could still play a decent game of bridge. If someone you love has Alzheimer’s, Restak says, don’t upset them by constantly challenging mistakes or memory lapses; instead, meet them where they are now.

“What are they still interested in? Talk about that, work with that, because a lot of things stay within normal range even with a pattern of dementia,” he says. “You don’t just look on it as a hopeless situation, although it’s a very frustrating one and it’s very sad.” Where a flicker of memory remains, perhaps, there’s hope.

on

… we have a small favour to ask. Tens of millions have placed their trust in the Guardian’s fearless journalism since we started publishing 200 years ago, turning to us in moments of crisis, uncertainty, solidarity and hope. More than 1.5 million supporters, from 180 countries, now power us financially – keeping us open to all, and fiercely independent.

Unlike many others, the Guardian has no shareholders and no billionaire owner. Just the determination and passion to deliver high-impact global reporting, always free from commercial or political influence. Reporting like this is vital for democracy, for fairness and to demand better from the powerful.

And we provide all this for free, for everyone to read. We do this because we believe in information equality. Greater numbers of people can keep track of the events shaping our world, understand their impact on people and communities, and become inspired to take meaningful action. Millions can benefit from open access to quality, truthful news, regardless of their ability to pay for it.

Every contribution, however big or small, powers our journalism and sustains our future. Support the Guardian from as little as $1 – it only takes a minute. If you can, please consider supporting us with a regular amount each month. Thank you.