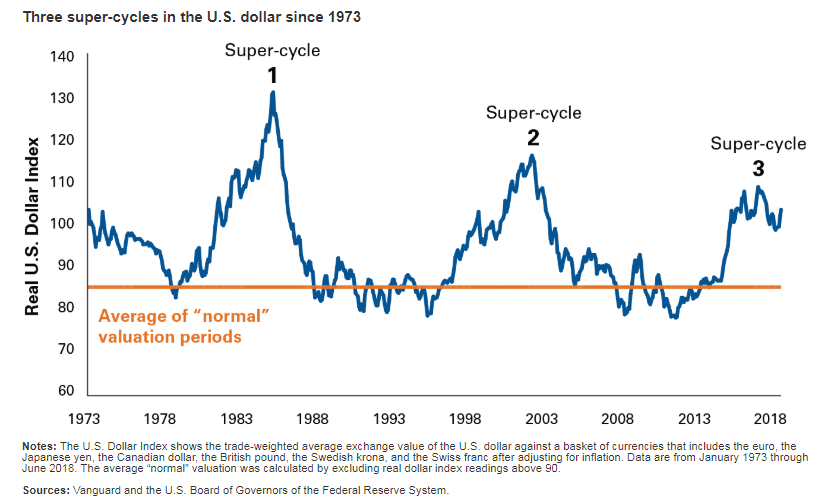

1.We are in Third Dollar Super Cycle Since 1973

Vanguard.

If past is prologue, the dollar will weaken

We can therefore expect the dollar super-cycle to come to a close over the next few years. Here are 4 fundamental factors, not mutually exclusive, that I’ll be watching for:

- Narrower growth differentials between the U.S. and other countries.The U.S. economy is much further along in the business cycle than other developed markets are, its labor market is much tighter, and inflation is much closer to the central bank’s target, which in the U.S. is 2%. Since economic growth normally slows late in the cycle, current growth differentials between the U.S. and other economies are expected to shrink. The next slowdown in the U.S. may be exacerbated when the recent fiscal stimulus wears off. We estimate that the stimulus, injected through the tax cuts and spending bill enacted at the beginning of the year, will deliver an extra push to U.S. economic growth of about 40 basis points this year and next.

- Higher U.S. bond yields, but narrowing interest rate differentials. Higher bond yields in the U.S. today imply depreciation in the U.S. dollar relative to other major currencies in the future. This market expectation may come to pass in the current global monetary cycle as the gap in rates between the U.S. and other major markets narrows. The Fed may stop raising rates as soon as 2019 while other central banks (notably the European Central Bank and the Bank of England) continue to play catch-up.

- Higher inflation in the U.S.Higher inflation in the U.S. relative to other developed markets could put downward pressure on the nominal U.S. dollar exchange rate.

- A larger U.S. trade deficit.For all the noise about tariffs and trade deficits, the natural way for trade imbalances to correct over time is through market-driven currency adjustments. Widening U.S. trade deficits translate into higher demand for foreign currency (to pay for the additional imports), which exerts downward pressure on the dollar. The trade deficits themselves are caused in part by rising government budget shortfalls, which spill over to more foreign purchases of U.S. debt, and in part by strong U.S. consumer spending, which, bolstered by tax cuts, results in more purchases of imported goods, given that they constitute about 18% of the typical consumer basket.

What’s behind the latest surge in the dollar?Roger Aliaga-Diaz

https://vanguardblog.com/2018/09/04/whats-behind-the-latest-surge-in-the-dollar/

2.GE New Lows..8th Largest Dividend Cut in S&P History.

It was the eighth-largest dividend cut in the history of the S&P 500, according to S&P Dow Jones Indices. Worse, GE (ticker: GE) now has three dividend cuts that rank in the top 10 in history, more than any other company.

General Electric Takes the Gold at Cutting Dividends By Lawrence C. Strauss

Barrons

https://www.barrons.com/articles/general-electric-takes-the-gold-at-cutting-dividends-1541196417

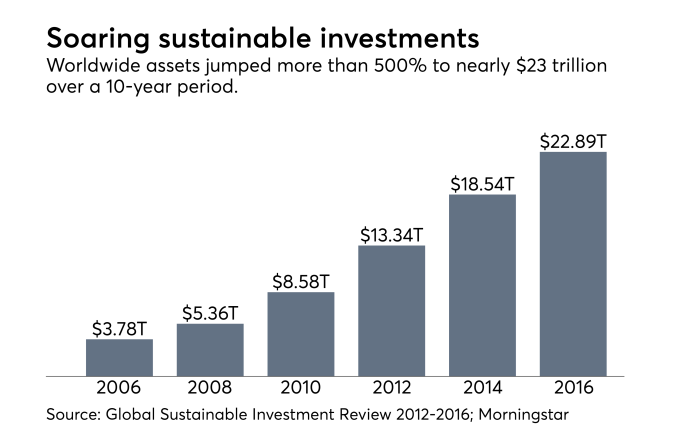

3.ESG 500% Growth in Assets…Calpers Re-Assessing Value Add?

https://www.financial-planning.com/news/how-financial-advisors-are-using-esg-investments

Barrons

ESG Investing Suffers a Setback in Californa By Vito J. Racanelli

https://www.barrons.com/articles/esg-investing-suffers-a-setback-in-california-1541200869

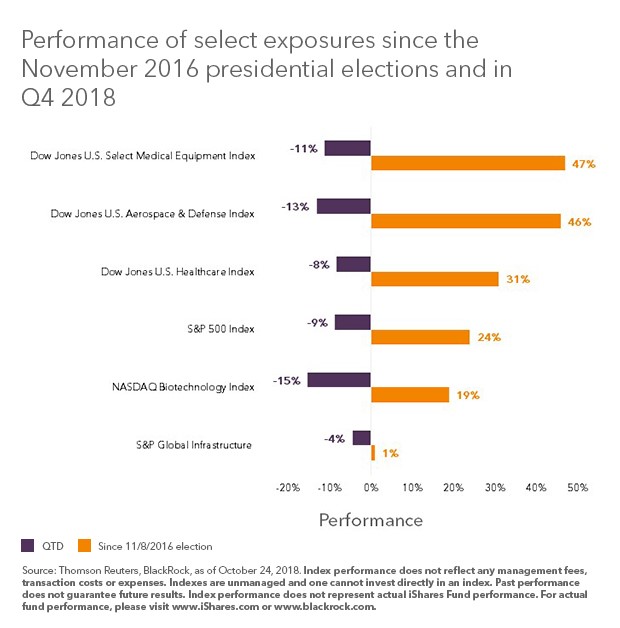

4.Looking past October’s Tricks to November’s Treats

Written by Christopher DhanrajHead of ETF Investment Strategy

Pay attention to these four industries heading into midterm elections.

Investor angst over the sustainability of earnings growth and the impact of trade tensions has pummeled equity markets. The upcoming midterm elections and their aftermath represent another catalyst that should be on investors’ radar, we believe. Taking a step back can be a good exercise. The S&P 500 Index has risen 27% since the 2016 elections, with big moves at the industry level as investors anticipated regulatory and political catalysts driven by a one-party hold amongst the executive and legislative branches.1

The October sell-off now brings the S&P 500 valuations down to a more reasonable 14.8x price to next year’s calendar earnings multiple–the lowest level in over 2 years. 1 As attractive valuations are an effective tool to bring investors back to the table, the following industry groups may be in focus as investors look past midterms to the end of the year.

BlackRock Blog

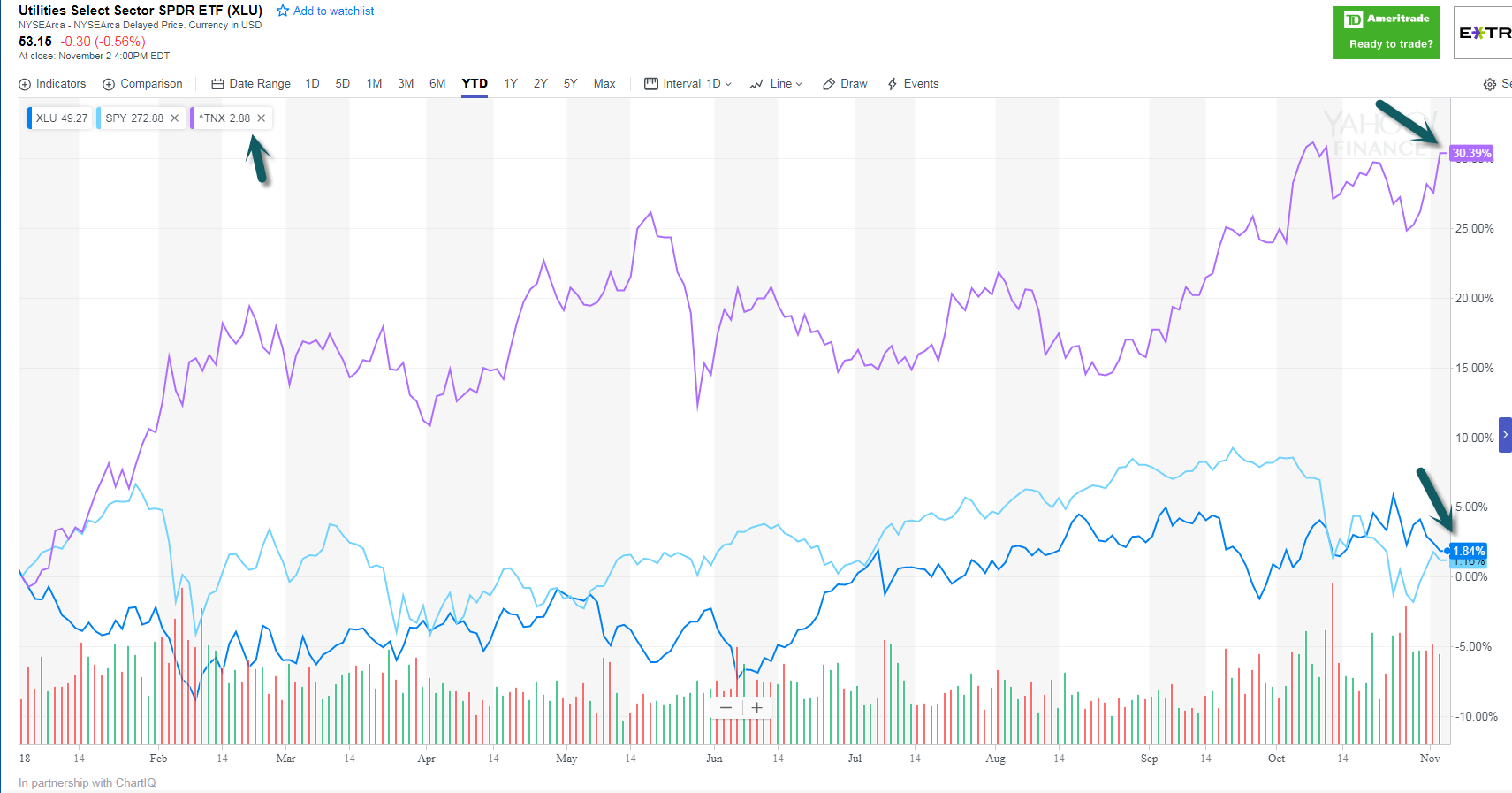

5.Interest Rates Using 10 Year Coupon Up 30% YTD and Utilities Still Outperforming S&P.

XLU Utilities ETF….SPY S&P….TNX 10 Year Rates.

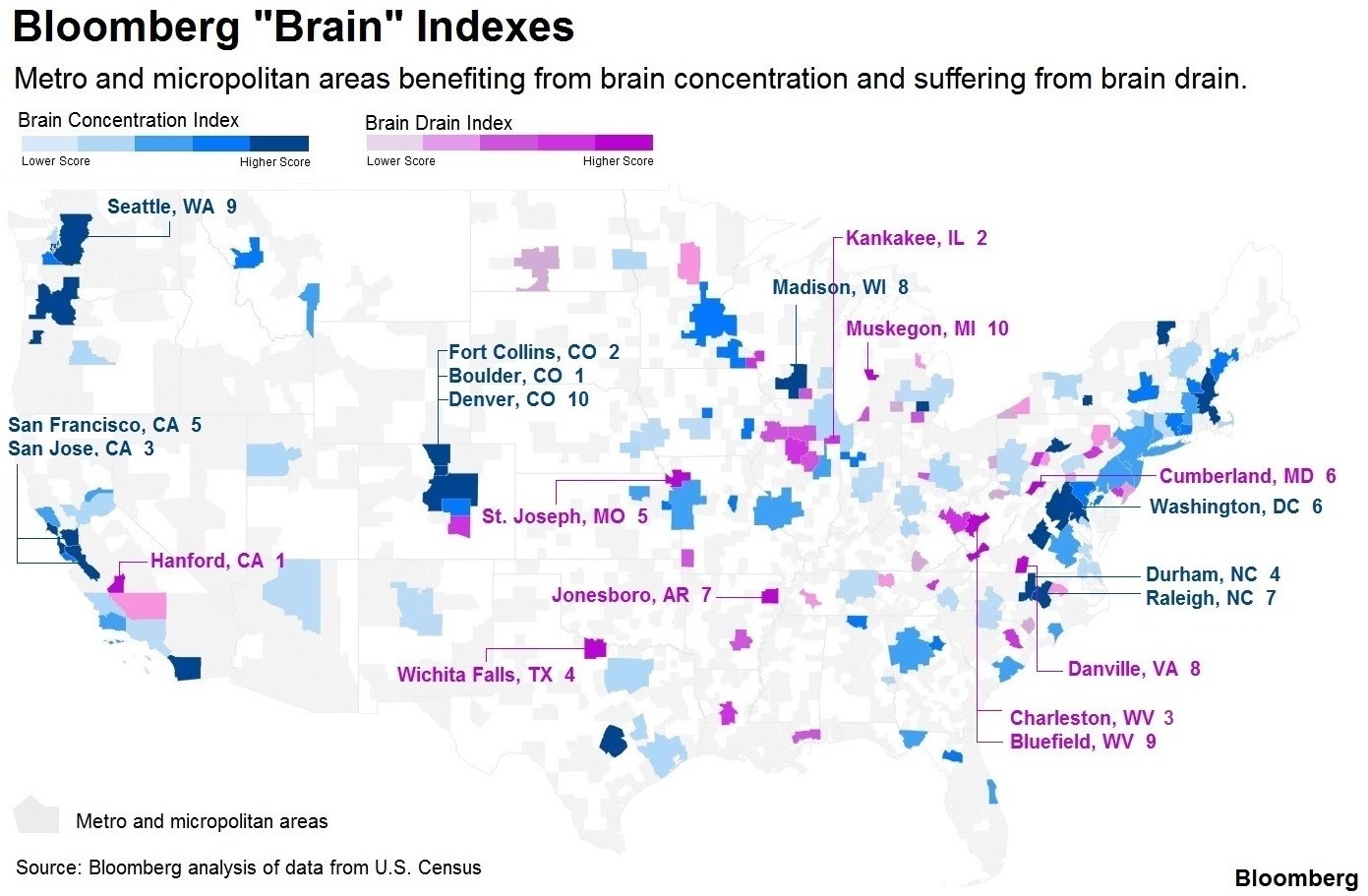

6.Where is the Intellectual Capital?

California’s affluent Silicon Valley wouldn’t be expected to see an exodus of skilled and highly educated workers but a drought, a lack of opportunities and a loss of manufacturers make this a reality for another part of the state — the hardscrabble Central Valley.

The Hanford-Corcoran metropolitan area — 175 miles southeast of the Silicon Valley — is No. 1 on this year’s Bloomberg Brain Drain Index, which tracks outflows of advanced degree holders and business formation, white collar job losses and reductions in pay in the fields of sciences, technology, engineering and mathematics.

These American Cities Are Losing the Most Brainpower By Sarah Foster Wei Lu and Vincent Del Giudice

Hanford, California, No. 1 on Bloomberg Brain Drain Index Boulder, Colorado, again tops Brain Concentration Index

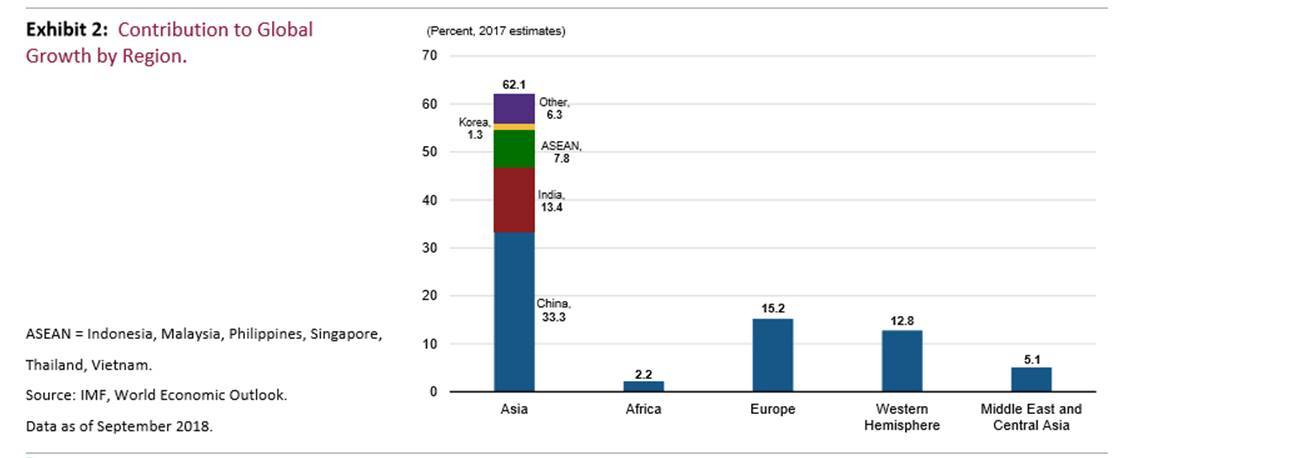

7.Asia Contributes 62% of World Ex-U.S. Growth.

https://www.valuewalk.com/2018/11/china-confronts-the-united-states/

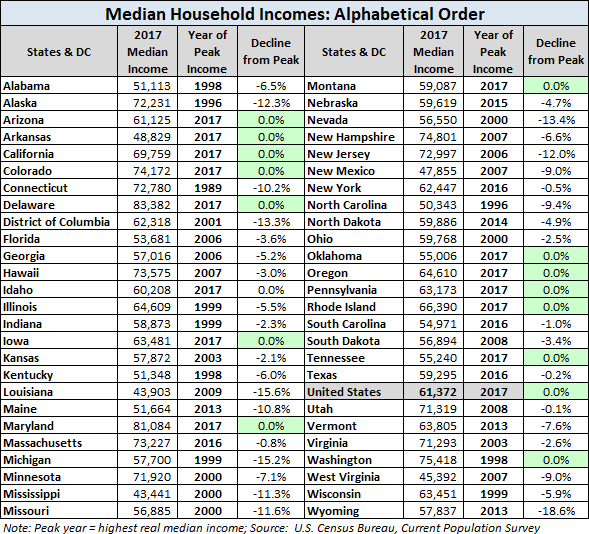

8.Median Household Income by State: 2017 Update

by Doug Short, 10/30/18

The Census Bureau’s annual household income report for 2017 was published last month. We’ve now compiled a few tables for the 50 states and DC based on the Current Population Survey, a joint undertaking of the Census Bureau and Bureau of Labor Statistics, which includes annual data from 1984 to 2017. The details are fascinating.

First, some context. The median US income in 2017 was $61,372, up from $21,575 in 1984 — a 184% rise over the 33-year time frame. However, if we adjust for inflation chained in 2017 dollars, the 1984 median is $50,511, and the increase drops to 17.7%.

9.Read of the Day…Dear Investor, That Cocky Voice in Your Head Is Wrong

The findings from the field of behavioral economics apply to everyone. Especially you.

ILLUSTRATION: HANNA BARCZYK

97 COMMENTS

By Jason Zweig

Aug. 24, 2018 7:00 a.m. ET

As much as all of us investors wish we were perfectly logical calculating machines, we are human: emotional, distractible, impatient, inconsistent. Behavioral economics is the study of how real human beings—not the walking, talking spreadsheets that traditional economists pretend we are—make financial decisions. Unfortunately, it’s all too easy to persuade yourself that the findings of behavioral economics apply to everyone else but you. After more than 20 years of studying research in that field, here’s how I think most investors interpret it. How many of these sound like you? I know many of them sound like me.

- Behavioral economics teaches that people are overconfident: They believe they know more than they do, or they assume their knowledge is more precise than it is.

I’m 100% certain that’s true for everybody else, but there’s no way that applies to me.

- Behavioral economists say that confirmation bias leads most people to seek out evidence supporting what they already believe or to ignore data that might disprove their beliefs.

That’s so ridiculous I’m not even going to waste my time refuting it.

- Behavioral economics says investors are myopic: Short-term losses or costs can blind them to the pursuit of longer-term rewards.

I could explain all that to you, but I gotta run.

- Behavioral economists say you should inform your decisions with the base rate, or the best available historical evidence of how likely an outcome is.

Why would I do that when my gut feelings give me the right answer, like, pretty much almost all the time?

- Extensive research documents unconscious biases, or factors that shape our behavior below the level of awareness.

Are you kidding me? I’m not aware a single decision of mine that could possibly have been affected by unconscious bias.

- Most people tend to be unrealistically optimistic, overestimating how likely they are to have good fortune and underestimating how many bad things will happen to them.

Ha! Just you wait until Facebook buys my great new scratch-n-sniff app for $10 billion!

- The disposition effectleads investors to sell their winning stocks too soon and hold onto their money-losing positions too long.

Well, I sure don’t suffer from that. I don’t have any losers!

- The sunk-cost fallacyleads many people to keep trying to justify a past decision even after it’s become obvious that it was a mistake.

That’s nonsense, and I’ll prove it to you after I finish checking the price on this stock I bought five years ago. [Pause.] I’ve only lost 85%, so I’ll be back to break-even in no time.

- Research in dozens of countries around the world shows that investors almost everywhere keep most of their stock portfolios in shares of local companies instead of spreading their bets worldwide. This “home bias” leaves them underexposed to the benefits of global diversification.

I’m not surprised people in backward countries would do something dumb like that. I’ve got at least 10% of my assets outside the U.S.!

- Research shows that many people are prone to “status-quo bias” or investing inertia, preferring to leave their current portfolio in place even when they might be better off switching to other choices.

But all my investments are already perfect. Why would I want to change?

- Behavioral economics shows that people are predictably bad at estimating probabilities: They tend to overestimate the likelihood of rare events and underestimate the frequency of common events.

Well, sure, but haven’t these scientists ever noticed somebody wins Powerball almost every week? The jackpot’s up to $459 million, so excuse me while I go buy 25 tickets.

- Many people exhibit what’s called the bias blind spot, or the tendency to see clearly that other people’s behavior isn’t optimal while remaining oblivious to our own shortcomings.

The more I think about it, the more I can see how that might apply to people like you.

- Experiments in behavioral economics show that most people are prone to anchoring. People who compare prices to the last digits of their Social Security number, for instance, are willing to pay more for something if their final digits are high.

People are so irrational! Hey, can you believe this guy on CNBC? He just said Apple stock’s going to $300 a share. There’s no way it’s worth more than, like, $285.

- Experiments have shown for decades that people tend to draw sweeping conclusions from extremely small samples of data.

Without even thinking about it, I can come up with three people who would never do that: me, myself and I.

- Decades of datashow that investors may overreact to relatively minor fluctuations in the stock market.

That’s nonsen—WHAT DO YOU MEAN, THE DOW IS DOWN 140 POINTS?

Write to Jason Zweig at intelligentinvestor@wsj.com

10.The Surprising Power of The Long Game

It’s easy to overestimate the importance of luck on success and underestimate the importance of investing in success every single day. Too often, we convince ourselves that success was just luck. We tell ourselves, the school teacher that left millions was just lucky. No. She wasn’t. She was just playing a different game than you were. She was playing the long game.

The long game isn’t particularly notable and sometimes it’s not even noticeable. It’s boring. But when someone chooses to play the long game from an early age, the results can be extraordinary. The long game changes how you conduct your personal and business affairs.

There is an old saying that I think of often, but I’m not sure where it comes from: If you do what everyone else is doing, you shouldn’t be surprised to get the same results everyone else is getting.

Ignoring the effect of luck on outcomes — the proverbial lottery ticket —doing what everyone else is doing pretty much ensures that you’re going to be average. Not average in the world, but average to people in similar circumstances. There are a lot of ways not to be average, but one of them is the tradeoff between the long game and the short game.

What starts small compounds into something more. The longer you play the long game, the easier it is to play and the greater the rewards. The longer you play the short game the harder it becomes to change and the bigger the bill facing you when you do want to change.

The Short Game

The short game is putting off anything that seems hard for doing something that seems easy or fun. The short game offers visible and immediate benefits. The short game is seductive.

- Why do your homework when you can go out and play?

- Why wait to pay for a phone in cash, when you can put it on your credit card?

- Why go to the gym when you can go drinking with your friends?

- Why invest in your relationship with your partner today when you can work a little bit extra in the office?

- Why learn something boring that doesn’t change when you can learn something sexy that impresses people?

- Why bust your butt at work to do the work before the meeting when you can read the executive summary and pretend like everyone else?

The effects of the short game multiply the longer you play. On any given day the impact is small but as days turn into months and years the result is enormous. People who play the short game don’t realize the costs until they become too large to ignore.

The problem with the short game is that the costs are small and never seem to matter much on any given day. Doing your homework today won’t give you straight A’s. Saving $5 today won’t make you a millionaire. Going to the gym and eating healthy today won’t make you fit. Reading a book won’t make you smart. Going to sleep on time tonight won’t make you healthier tomorrow. Sure we might try these things when we’re motivated but since the results are not immediate we revert back to the short game.

As the weeks turn into months and the months into years, the short game compounds into disastrous results. It’s not the one day trade off that matters but it’s accumulation.

Playing the long game means suffering a little today. And why would we want to suffer today when we can suffer tomorrow. But if our intention is to always change tomorrow, then tomorrow never comes. All we have is today.

The Long Game

The long game is the opposite of the short game, it means paying a small price today to make tomorrow’s tomorrow easier. If we can do this long enough to see the results, it feeds on itself.

From the outside, the long game looks pretty boring:

- Saving money and investing it for tomorrow

- Leaving the party early to go get some sleep

- Investing time in your relationship today so you have a foundation when something happens

- Doing your homework before you go out to play

- Going to the gym rather than watching Netflix

… and countless other examples.

In its simplest form, the long game isn’t really debatable. Everyone agrees, for example, we should spend less than we make and invest the difference. Playing the long game is a slight change, one that seems insignificant at the moment, but one that becomes the difference between financial freedom and struggling to make next month’s rent.

The first step to the long game is the hardest. The first step is visibly negative. You have to be willing to suffer today in order to not suffer tomorrow. This is why the long game is hard to play. People rarely see the small steps when they’re looking for enormous outcomes, but deserving enormous outcomes is mostly the result of a series of small steps that culminate into something visible.

Conclusion

In everything you do, you’re either playing a short term or long term game. You can’t opt out and you can’t play a long-term game in everything, you need to pick what matters to you. But in everything you do time amplifies the difference between long and short-term games. The question you need to think about is when and where to play a long-term game. A good place to start is with things that compound: knowledge, relationships, and finances.

This article is an expansion of something I originally touched on here.