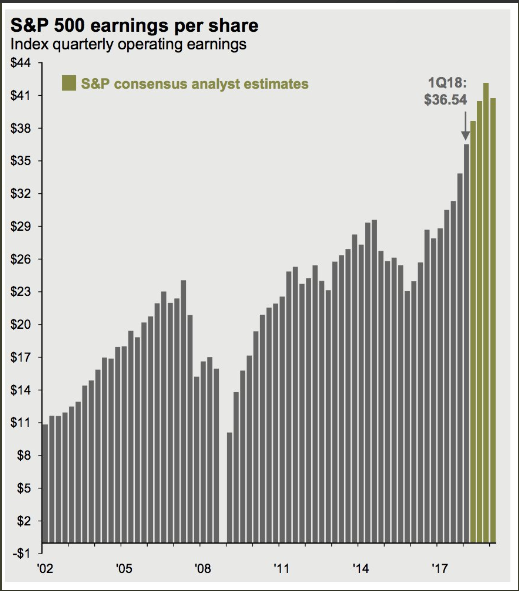

1.Earnings Hit A Record.

Michael Batnick on Twitter

https://twitter.com/michaelbatnick

2.Oil Prices vs. Oil Stocks.

SPDR BLOG

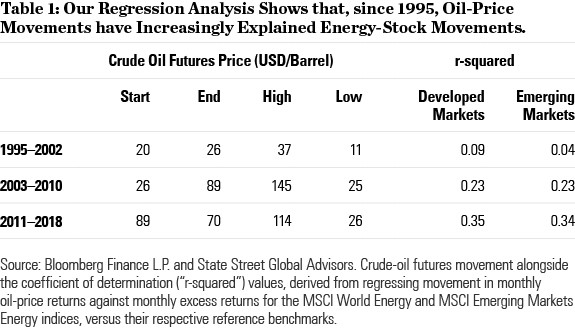

Focusing our attention on domestic markets, during the period from 1995 to 2002, oil stayed in a range of $15 to $35. For every 10% move in the oil price, stock prices in the energy sector would only move around 2.5% in excess of the market return, on average. The explanatory power of this relationship was low, with a coefficient of determination (or “r-squared”) value of just 0.09. In other words, only 9 percent of the variability in energy-sector excess returns could be explained by changes in the oil price over this period. (See Table 1.)

The picture changed during the period from 2003 to 2010, when the oil price went on a tear from $20 to $140 and back down to $35. Looking again at domestic markets, the relationship between the commodity and the stocks in this time frame was much stronger. Every 10% move in oil price corresponded with about a 5% move on average in excess returns for energy stocks, with an r-squared of 0.23.

Over the most recent seven years, the relationship between oil prices and energy-sector has been similar. During this period in domestic markets, oil has traded from $80 a barrel up to $110, then down to $30 and back up to current levels of $70. From 2011 to 2018, a 10% move in oil would on average lead to a 5% move in energy stock prices, yielding an even higher r-squared of 0.35.

What about in emerging markets? A very similar relationship took shape between oil prices and energy-stock excess returns. In our earliest period, from 1995 to 2002, the r-squared value in this analysis for emerging markets was only 0.04. In the middle period, from 2003 to 2010, r-squared for emerging markets was higher, at 0.23. In the most recent period, from 2010 to 2018, r-squared was higher still at 0.34, again in line with domestic markets.

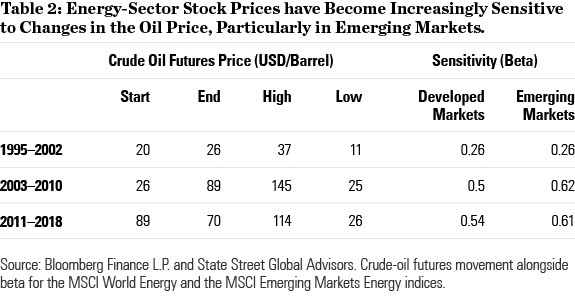

An analysis of the risk measure, beta, reinforces the overall point: as oil price gained explanatory power vis-à-vis energy-stock prices, stock prices in the energy sector also became increasingly sensitive to oil-price volatility. (See Table 2.) This is particularly true in emerging markets, where beta analysis shows that energy stocks generally respond more directly to oil-price changes than in developed markets.

DON’T WASTE RESOURCES ON FORECASTING THE OIL PRICE WHEN CHOOSING ENERGY STOCKS= Olivia Engel

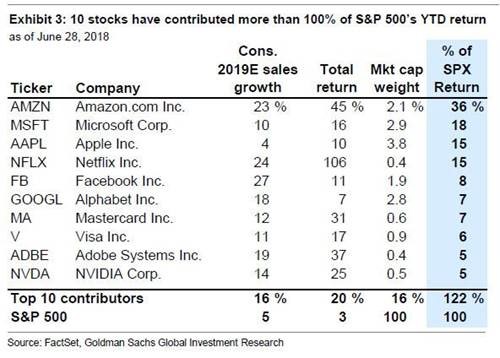

3.Top 4 Stocks Responsible for 84% of S&P 2018 Upside.

And another striking fact: just the Top 4 stocks, Amazon, Microsoft, Apple and Netflix have been responsible for 84% of the S&P upside in 2018 (and yes, these are more or less the stocks David Einhorn is short in his bubble basket, which explains his -19% YTD return).

https://www.zerohedge.com/news/2018-07-01/amazon-alone-responsible-more-third-sps-return-year

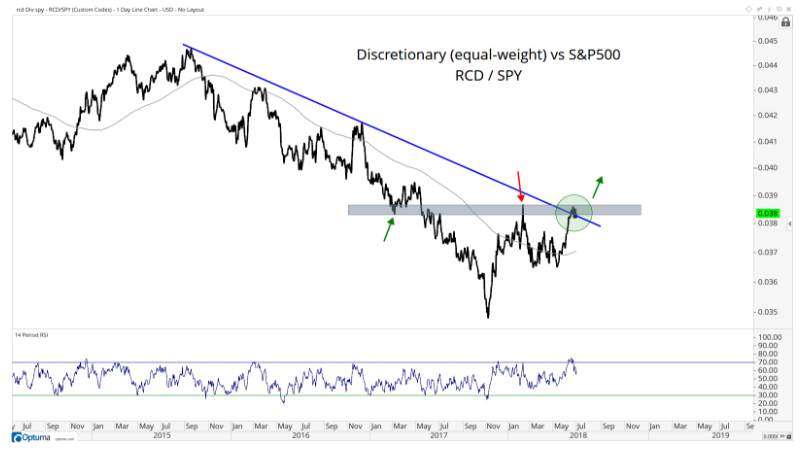

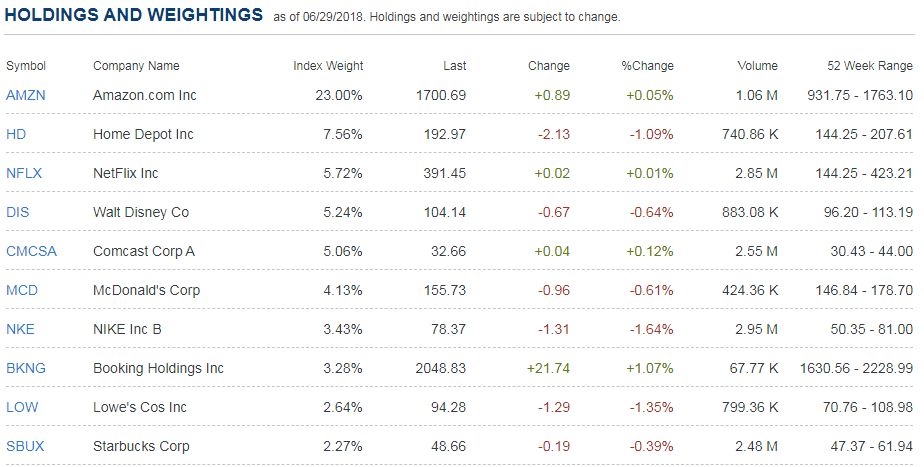

4.Interesting Chart of Consumer Discretionary Stocks Backing Out AMZN (22% of index)

JC Parets All-Star Charts.

But Parets backed out Amazon from the XLY and found that, even without the massive boost, “we are in the midst of what could be the end of a 3-year relative downtrend,” as illustrated in this chart:

Along with Amazon, the ETF’s top holdings also include Netflix NFLX, +1.72% and Home HD, -0.55% Here are the 10 biggest positions:

“A breakout here would be confirmation that discretionaries, as a group, are heading higher, and therefore very difficult to be bearish stocks,” Parets concluded. “I think we rally.”

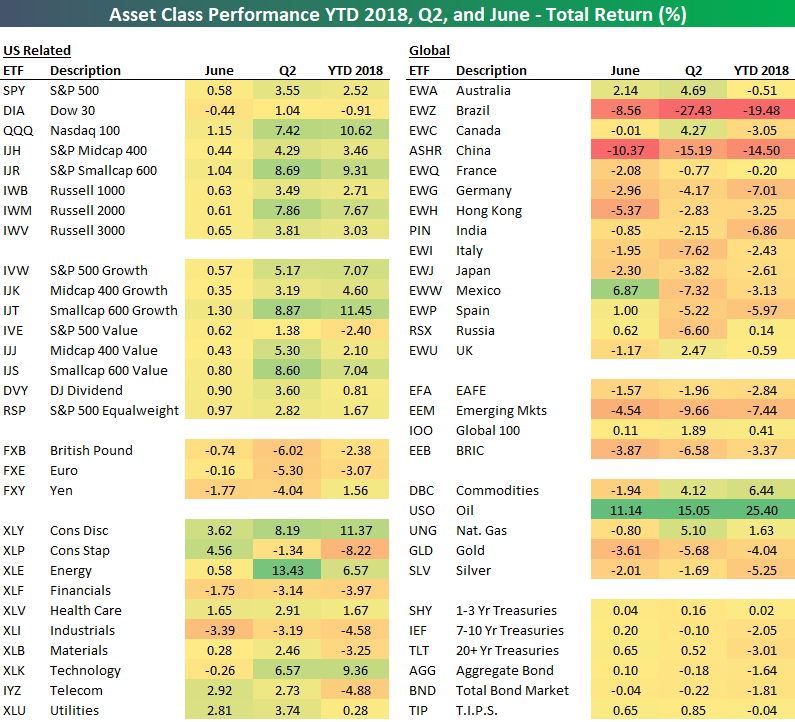

5.First Half Summary…Growth Continues to Beat Value…Small Cap Best First Half vs. Large Since 2010.

First Half 2018 Asset Class Performance Matrix

Jul 2, 2018

Below is our total return matrix highlighting the performance of various asset classes during the first half of 2018 from the perspective of a US investor focused on ETFs.

At the halfway point of 2018, small-caps have trumped large-caps, while growth has crushed value. Looking at sectors, Consumer Discretionary (XLY), Technology (XLK), and Energy (XLE) have been the best performers so far this year, while Consumer Staples (XLP), Financials (XLF), Materials (XLB), and Industrials (XLI) are solidly in the red.

Outside of the US, equity markets have struggled this year. Of the 14 country ETFs in our matrix, Russia (RSX) is the only one that finished the first half in the green, and it was in the green by just 14 basis points at that. Brazil (EWZ) and China (ASHR) enter the second half down on the year by 19.48% and 14.50%, respectively.

Looking at commodities, oil (USO) is up more than any asset class in our matrix at +25.40%. Gold (GLD) and silver (SLV) are both down 4%+. Treasury ETFs are down on the year as interest rates have risen.

https://www.bespokepremium.com/think-big-blog/

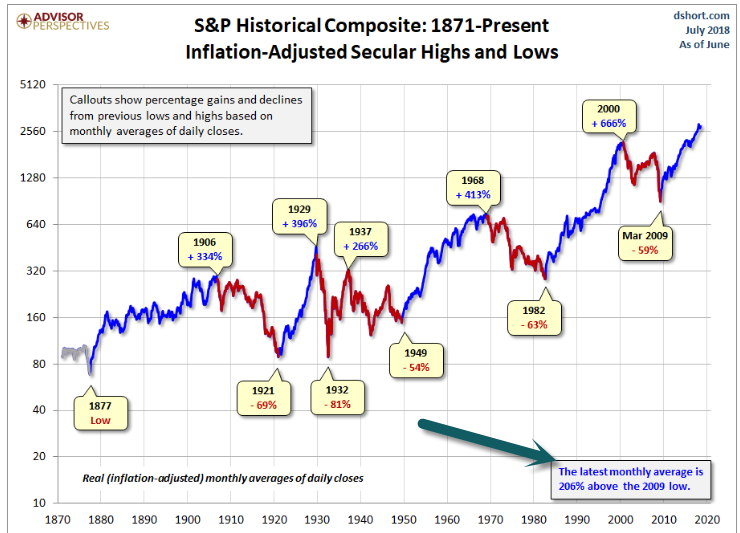

6.Inflation Adjusted Look at Bull Markets.

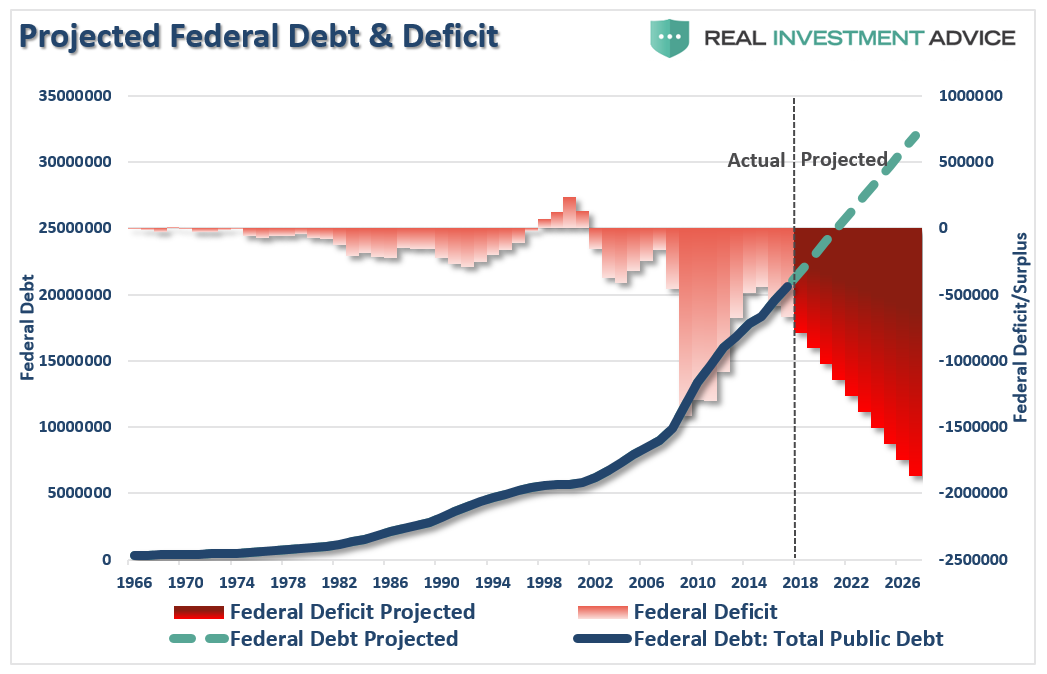

7.2007 Deficit $161Billion….2018 $804Billion….Debt to GDP 65% 2008…105% 2018

https://www.investing.com/analysis/cbo–making-america-more-indebted-200304975

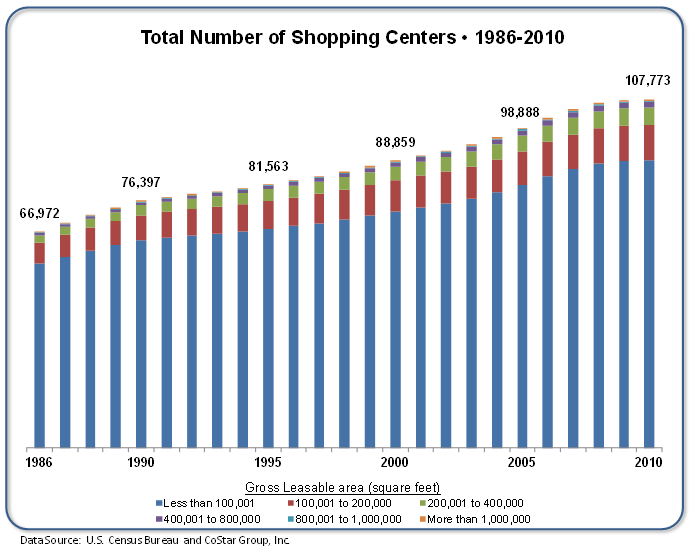

8.Mall Vacancy Hang Over From Decades of Build Out

Malls Vacancies Hit Six-Year High as Online Shopping Takes a Toll

Toll is felt across all types of brick-and-mortar outlets in the U.S. as iconic retail names close stores

By

Esther Fung

Malls are the emptiest they’ve been since 2012, when the U.S. economy was still struggling to recover from the last recession.The vacancy rate reached 8.6% in the second quarter, up from 8.4% in the first quarter, as more consumers shifted their shopping online, according to data from real-estate research firm Reis Inc. REIS 0.46%The highest postrecession vacancy was in the third quarter of 2011, when it hit 9.4%, Reis said.

Shopping Center Growth Pre Amazon.

9.Read of the Day…‘A way of monetizing poor people’: How private equity firms make money offering loans to cash-strapped Americans

Mariner Finance, a fast-growing consumer lending company, has been accused of predatory practices. Many of their customers end up in court buried in debt. (Jon Gerberg/The Washington Post)

by Peter Whoriskey July 1 Email the author

The check arrived out of the blue, issued in his name for $1,200, a mailing from a consumer finance company. Stephen Huggins eyed it carefully.

A loan, it said. Smaller type said the interest rate would be 33 percent.

Way too high, Huggins thought. He put it aside.

A week later, though, his 2005 Chevy pickup was in the shop, and he didn’t have enough to pay for the repairs. He needed the truck to get to work, to get the kids to school. So Huggins, a 56-year-old heavy equipment operator in Nashville, fished the check out that day in April 2017 and cashed it.

Within a year, the company, Mariner Finance, sued Huggins for $3,221.27. That included the original $1,200, plus an additional $800 a company representative later persuaded him to take, plus hundreds of dollars in processing fees, insurance and other items, plus interest. It didn’t matter that he’d made a few payments already.

“It would have been cheaper for me to go out and borrow money from the mob,” Huggins said before his first court hearing in April.

As treasury secretary in the Obama administration, Timothy F. Geithner condemned predatory lenders. Now he is president of Warburg Pincus, a New York firm that controls a private equity fund that owns Mariner Finance. (Andrew Harrer/Bloomberg News)

Most galling, Huggins couldn’t afford a lawyer but was obliged by the loan contract to pay for the company’s. That had added 20 percent — $536.88 — to the size of his bill.

“They really got me,” Huggins said.

A growing market

Mass-mailing checks to strangers might seem like risky business, but Mariner Finance occupies a fertile niche in the U.S. economy. The company enables some of the nation’s wealthiest investors and investment funds to make money offering high-interest loans to cash-strapped Americans.

funds to make money offering high-interest loans to cash-strapped Americans.

Mariner Finance is owned and managed by a $11.2 billion private equity fund controlled by Warburg Pincus, a storied New York firm. The president of Warburg Pincus is Timothy F. Geithner, who, as treasury secretary in the Obama administration, condemned predatory lenders. The firm’s co-chief executives, Charles R. Kaye and Joseph P. Landy, are established figures in New York’s financial world. The minimum investment in the fund is $20 million.

Mariner Finance operates more than 450 branches in 22 states, according to company filings. It is especially active in Virginia, Maryland, Tennessee, Pennsylvania and Florida. Above, a store in District Heights, Md. (Salwan Georges/The Washington Post)

Dozens of other investment firms bought Mariner bonds last year, allowing the company to raise an additional $550 million. That allowed the lender to make more loans to people like Huggins.

“It’s basically a way of monetizing poor people,” said John Lafferty, who was a manager trainee at a Mariner Finance branch for four months in 2015 in Nashville. His misgivings about the business echoed those of other former employees contacted by The Washington Post. “Maybe at the beginning, people thought these loans could help people pay their electric bill. But it has become a cash cow.”

The market for “consumer installment loans,” which Mariner and its competitors serve, has grown rapidly in recent years, particularly as new federal regulations have curtailed payday lending, according to the Center for Financial Services Innovation, a nonprofit research group. Private equity firms, with billions to invest, have taken significant stakes in the growing field.

Among its rivals, Mariner stands out for the frequent use of mass-mailed checks, which allows customers to accept a high-interest loan on an impulse — just sign the check. It has become a key marketing method.

The company’s other tactics include borrowing money for as little as 4 or 5 percent — thanks to the bond market — and lending at rates as high as 36 percent, a rate that some states consider usurious; making millions of dollars by charging borrowers for insurance policies of questionable value; operating an insurance company in the Turks and Caicos, where regulations are notably lax, to profit further from the insurance policies; and aggressive collection practices that include calling delinquent customers once a day and embarrassing them by calling their friends and relatives, customers said.

Finally, Mariner enforces its collections with a busy legal operation, funded in part by the customers themselves: The fine print in the loan contracts obliges customers to pay as much as an extra 20 percent of the amount owed to cover Mariner’s attorney fees, and this has helped fund legal proceedings that are both voluminous and swift. Last year, in Baltimore alone, Mariner filed nearly 300 lawsuits. In some cases, Mariner has sued customers within five months of the check being cashed.

The company’s pace of growth is brisk — the number of Mariner branches has risen eightfold since 2013. A financial statement obtained by The Post for a portion of the loan portfolio indicated substantial returns.

Mariner Finance officials declined to grant interview requests or provide financial statements, but they offered written responses to questions.

Company representatives described Mariner as a business that yields reasonable profits while fulfilling an important social need. In states where usury laws cap interest rates, the company lowers its highest rate — 36 percent — to comply.

“The installment lending industry provides an important service to tens of millions of Americans who might otherwise not have safe, responsible access to credit,” John C. Morton, the company’s general counsel, wrote. “We operate in a competitive environment on narrow margins, and are driven by that competition to offer exceptional service to our customers. . . . A responsible story on our industry would focus on this reality.”

Regarding the money that borrowers pay for Mariner’s attorneys, the company representatives noted that those payments go only toward the attorneys it hires, not to Mariner itself.

The company declined to discuss the affiliated offshore company that handles insurance, citing competitive reasons. Mariner sells insurance policies that are supposed to cover a borrower’s loan payments in case of various mishaps — death, accident, unemployment and the like.

“It is not our duty to explain to reporters . . . why companies make decisions to locate entities in different jurisdictions,” Morton wrote.

Through a Warburg Pincus spokesman, Geithner, the company president, declined to comment. So did other Warburg Pincus officials. Instead, through spokeswoman Mary Armstrong, the firm issued a statement:

“Mariner Finance delivers a valuable service to hundreds of thousands of Americans who have limited access to consumer credit,” it says. “Mariner is licensed, regulated, and in good standing, in all states in which it operates and its operations are subject to frequent examination by state regulators. Mariner’s products are transparent with clear disclosure and Mariner proactively educates its customers in every step of the process.”

Equity firms’ stakes

Over the past decade or so, private equity firms, which pool money from investment funds and wealthy individuals to buy up and manage companies for eventual resale, have taken stakes in companies that offer loans to people who lack access to banks and traditional credit cards.

Some private equity firms have bought up payday lenders. Today, prominent brands in that field, such as Money Mart, Speedy Cash, ACE Cash Express and the Check Cashing Store, are owned by private equity funds.

Other private equity firms have taken stakes in “consumer installment” lenders, such as Mariner, and these offer slightly larger loans — from about $1,000 to more than $25,000 — for longer periods of time.

Today, three of the largest companies in consumer installment lending are owned to a significant extent by private equity funds — Mariner is owned by Warburg Pincus; Lendmark Financial Services is held by the Blackstone Group, which is led by billionaire Stephen Schwarzman; and a portion of OneMain Financial is slated to be purchased by Apollo Global, led by billionaire Leon Black, and Varde Partners.

These lending companies have undergone significant growth in recent years. To raise more money to lend, they have sold bonds on Wall Street.

“Some of the largest private equity firms today are supercharging the payday and subprime lending industries,” said Jim Baker of the Private Equity Stakeholder Project, a nonprofit organization that has criticized the industry. In some cases, “you’ve got billionaires extracting wealth from working people.”

Exactly how much Mariner Finance and Warburg Pincus are making is difficult to know.

Mariner Finance said that the company earns a 2.6 percent rate of “return on assets,” a performance measure commonly used for lenders that measures profits as a percentage of total assets. Officials declined to share financial statements that would provide context for that number, however. Banks typically earn about a 1 percent return on assets, but other consumer installment lenders have earned more.

The financial statements obtained by The Post for “Mariner Finance LLC” indicate ample profits. Those financial statements have limitations: “Mariner Finance LLC” is one of several Mariner entities; the statements cover only the first nine months of 2017; and they don’t include the Mariner insurance affiliate in Turks and Caicos. Mariner Finance objected to The Post citing the figures, saying they offered only a partial view of the company.

The “Mariner Finance LLC” documents show a net profit before income taxes of $34 million; retained earnings, which include those of past years, of $145 million; and assets totaling $561 million. Two independent accountants who reviewed the documents said the figures suggest a strong financial performance.

“They are not hurting at least in terms of their profits,” said Kurt Schulzke, a professor of accounting and business law at Kennesaw State University, who reviewed the documents. “They’ve probably been doing pretty well.”

New management

As treasury secretary, Geithner excoriated predatory lenders and their role in the Wall Street meltdown of 2007. Bonds based on subprime mortgages, he noted at the time, had a role in precipitating the panic.

“The financial crisis exposed our system of consumer protection as a dysfunctional mess, leaving ordinary Americans way too vulnerable to fraud and other malfeasance,” Geithner wrote in his memoir, “Stress Test.” “Many borrowers, especially in subprime markets, bit off more than they could chew because they didn’t understand the absurdly complex and opaque terms of their financial arrangements, or were actively channeled into the riskiest deals.”

In November 2013, it was announced that Geithner would join Warburg Pincus as president. Months earlier, one of the firm’s funds had purchased Mariner Finance for $234 million.

Under the management of Warburg Pincus, Mariner Finance has expanded briskly.

When it was purchased, the company operated 57 branches in seven states. It has since acquired competitors and opened dozens of branches. It now operates more than 450 branches in 22 states, according to company filings.

Twice last year, Mariner Finance raised more money by issuing bonds based on its loans to “subprime” borrowers — that is, people with imperfect credit.

Ex-workers share qualms

To get a better idea of business practices at this private company, The Post reviewed documents filed for state licensing, insurance company documents, scores of court cases, and analyses of Mariner bond issues by Kroll Bond Rating Agency and S&P Global Ratings; obtained the income statement and balance sheet covering most of last year from a state regulator; and interviewed customers and a dozen people who have worked for the company in its branch locations.

Mariner Finance has about 500,000 active customers, who borrow money to cover medical bills, car and home repairs, and vacations. Their average income is about $50,000. As a group, Mariner’s target customers are risky: They generally rank in the “fair” range of credit scores. About 8 percent of Mariner loans were written off last year, according to a report by S&P Global Ratings, with losses on the mailed loans even higher. By comparison, commercial banks typically have suffered losses of between 1 and 3 percent on consumer loans.

Despite the risks, however, Mariner Finance is eager to gain new customers. The company declined to say how many unsolicited checks it mails out, but because only about 1 percent of recipients cash them, the number is probably in the millions. The “loans-by-mail” program accounted for 28 percent of Mariner’s loans issued in the third quarter of 2017, according to Kroll. Mariner’s two largest competitors, by contrast, rarely use the tactic.

Mariner generally targets people who have imperfect credit scores, according to the bond rating agencies. After a mailed check is cashed by a recipient, a Mariner rep follows up and solicits more information about the borrower — this helps in collections — and sometimes proposes additional lending. About half of the loans that begin with an unsolicited check are later converted into conventional loans.

“Our customer satisfaction rates with this product are exceptional,” wrote Morton, the company’s general counsel. He said that only about .02 percent of the mailed loan accounts lead to complaints.

Ten of the 12 former employees whom The Post contacted, however, expressed qualms about the company’s sales practices, describing an environment where meeting monthly goals seemed at times to rely on customer ignorance or distress. Those interviewed worked in branches across five states where Mariner is especially active: Virginia, Maryland, Tennessee, Pennsylvania and Florida.

“I didn’t like the idea of dragging people down into debt — they really make it a big deal to call and collect and not take no for an answer,” said Asha Kabirou, 28, a former customer service representative in two Maryland locations in 2014. “If someone started to fall behind on their payments — which happened a lot — they would say, ‘Why don’t we offer you another $200?’ But they wouldn’t have the money the next month, either.”

“Were there a few loans that actually helped people? Yes. Were 80 percent of them predatory? Probably,” said one former branch manager who was at the company in 2016. He spoke on the condition of anonymity, saying he did not want to antagonize his former employer. “I’m still embarrassed by some of the things I did there.”

“The company is here to make money — I understand that,” said Mauricio Posso, 28, who worked at a Northern Virginia location in 2016 and said he viewed it as valuable work experience. “At the same time, it’s taking advantage of customers. Most customers do not read what they get in the mail. It’s just little tiny type. They just see the $1,200 for you. . . . It can be a win-win. In some situations, it was just a win for us.”

While Mariner and industry advocates note that consumers can simply decline a loan if the terms are onerous, at least some of them may lack the time, English skills or other knowledge to shop around. Some are acutely in need of cash.

“I wanted to go to my mother’s funeral — I needed to go to Laos,” Keo Thepmany, a 67-year-old from Laos who is a housekeeper in Northern Virginia, said through an interpreter. To cover costs, she took out a loan from Mariner Finance and then refinanced and took out an additional $1,000. The new loan was at a rate of 33 percent and cost her $390 for insurance and processing fees.

She fell behind, and Mariner filed suit against her last year for $4,200, including $703 for attorney fees. The company also sought a court order to take out money from her wages.

Barbara Williams, 72, a retired school custodian from Prince William County, in Northern Virginia, said she cashed a Mariner loan check for $2,539 because “I wanted to get my teeth fixed. And I wanted to pay my hospital bills.”

She’d been in the hospital with three mini-strokes and pneumonia, she said. Within a few months, Mariner suggested she borrow another $500, and she did. She paid more than $350 for fees and insurance on the loan, according to the loan documents. The interest rate was 30 percent.

“It was kind of like I was in a trance,” she said of her decision to borrow from Mariner. She paid back some of the money but then fell behind, and Mariner sued. The company won court judgment against her in April for $3,852, including $632 in fees for Mariner’s attorney.

A lucrative addition

The other pool of Mariner Finance revenue comes from selling insurance polices.

Mariner pitches the insurance policies to customers as a way of paying off a loan in case of mishaps: There is a life insurance policy that promises to make the loan payments if you die, an unemployment policy that makes the payments if you lose your job, and an accident and disability policy in case of those possibilities.

Mariner also sells a car club membership that covers the cost of repairs.

These can add several hundred dollars to a loan.

The insurance policies provide “tangible benefits” for customers whose financial arrangements are vulnerable to life’s interruptions, the company said.

Customers are supposed to be informed that the insurance policies are optional. Several former employees alleged that some salesmen tacked on these products and waited for customers to object. They likened it to the add-ons that pad the bill when buying a car.

“If you sold a car club membership, you were like a god,” said a former assistant branch manager in Pennsylvania.

When Mariner salesmen were closing a loan and “went to print out the loan contract, they would just automatically add the insurance on there — every time,” Kabirou, the customer service representative said. “Clients would say, ‘Do I really need it?’ And the person would say, ‘Yes, you need to be covered.’ ”

In response, the company said steps are taken to make sure that customers understand that the insurance is optional.

The company has “numerous safeguards in place to make sure that all of our products are sold in a responsible manner. . . . Our audit teams regularly visit branch locations and monitor loan closings to ensure that our employees are explaining all products correctly. And we call a randomly selected subset of new customers every day to make sure they understand the terms of the loans.”

Mariner makes money from the insurance sales in two ways.

First, Mariner gets a commission from the insurance companies for selling the policies.

Mariner sells insurance policies issued by Lyndon Southern and Life of the South, and these two companies often give sales commissions of as much as 50 percent of the premium price, according to statistics filed with the National Association of Insurance Commissioners.

Mariner Finance officials declined to say how much of a commission Mariner receives on insurance policies it sells.

The second way that Mariner profits from the insurance sales is through its insurance company registered in Turks and Caicos. That company, too, earns money on policies issued by Life of the South and Lyndon Southern.

Essentially, it works like this: Mariner sells the insurance policies written by the two companies. Those two insurance companies, in turn, buy reinsurance from Mariner’s offshore affiliate, called MFI Insurance. Last year, those two insurance companies ceded $20 million in premiums back to MFI, according to documents filed in Delaware, where Lyndon Southern is based, and from Georgia, where Life of the South is.

Mariner declined to discuss its offshore insurance company. According to a Turks and Caicos financial regulator, it is the ease of doing business there — not laxity of regulation — that attracts companies to set up shop there.

“We have a risk-appropriate regulatory framework,” said Niguel Streete, managing director of the Turks and Caicos Islands Financial Services Commission.

But numerous business experts have advised U.S. insurers to set up shop in Turks and Caicos to avoid regulation.

“Much of the appeal of an offshore reinsurer is the modest regulatory climate,” according to a guidebook published by an insurance consulting agency known as CreditRe. Many such reinsurers “were developed as a legal mechanism to generate potential total income in excess of the [state-mandated] commission caps.”

The trouble with the insurance policies like the ones that Mariner sells to borrowers is that they devote so little money to covering claims, said Birny Birnbaum, executive director of the consumer advocacy organization Center for Economic Justice, which has issued reports on the credit insurance industry. He formerly served as the Texas Department of Insurance’s chief economist.

“At the end of the day, these lenders take far more in profit from the insurance premium than the amount paid in benefits for the consumer,” Birnbaum said.

Some regulators call for insurers to allocate at least 60 percent of premiums collected for covering customer claims; by contrast, some of the policies from Life of the South return as little as 20 percent to consumers; the policies from Lyndon Southern offer as little as 9 percent on average, according to the NAIC statistics.

Take, for example, the unemployment policy that Huggins bought from Lyndon Southern. The insurance cost Huggins a total of $172.

The average Lyndon Southern unemployment policy gives half of the premium back to the seller as a commission, according to the NAIC statistics. Less than 9 percent of premiums goes to covering customer claims, an extraordinarily low number, insurance experts said.

Life of the South and Lyndon Southern did not respond to requests for comment. Neither did the parent company of the insurers, known as Fortegra.

So far, Huggins’s unemployment policy hasn’t done him much good. He thought he was covered when he became unemployed last year and informed Mariner Finance. Instead, Mariner Finance summoned him to court.

Huggins said he’s worried about how disruptive the court case may be. He’s lost a day or two from work. More ominously, while he had hoped to raise his credit score enough to buy a house, a legal judgment against him could undo those plans. He and his stepkids are renting a place from a friend for now.

“Who sends someone $1,200 in the mail that they don’t know nothing about except maybe their credit score?” he said. “It was postdated, good for a month. I guess they give you a month to sit around and look at it and everything else until you just convince yourself you really need that money. . . .

“You think they’re helping you out — and what they’re doing is they’re sinking you further down,” he said. “They’re actually digging the hole deeper and pushing you further down.”

Jon Gerberg contributed to this report.

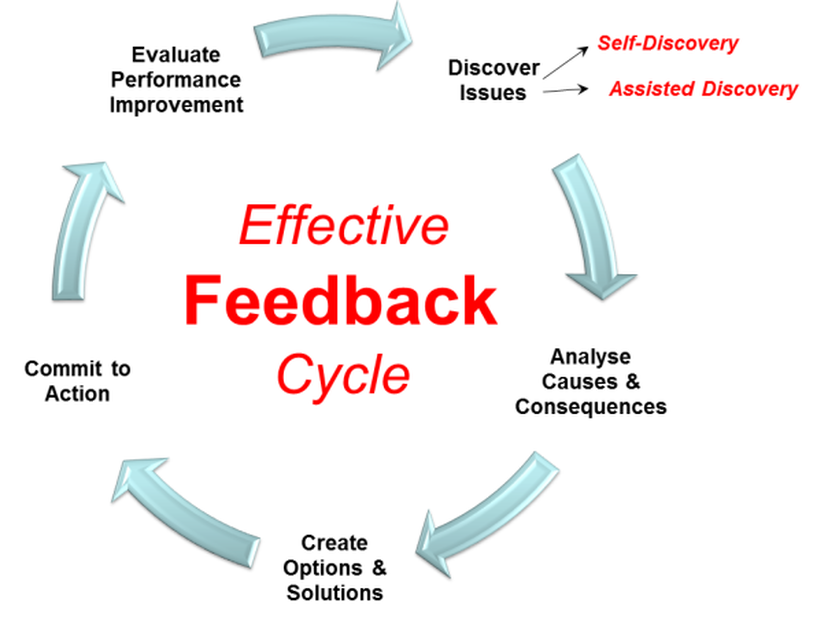

10.Use This 5-Step Feedback “Cycle” to Improve Your Business and Relationships

by Craig Ballantyne | Jul 2, 2018 | Articles, Motivation, Self-Improvement, Skill Development

I’ve been broke. I’ve been a drunk. I’ve been a jerk.

I’ve had social anxiety so bad that I would go to seminars and request a hotel room on the lowest floor possible so that I didn’t have to take the elevator with strangers.

That all changed thanks to a simple feedback cycle that has made me “normal,” richer than I ever thought possible, and the owner of my dream business.

Today, I rarely consume alcohol, and when I do, I can always stop at one drink.

When I ride in elevators, I greet everyone that enters and sometimes even tell jokes to strangers.

People who knew me 10 years ago can’t believe how much I’ve changed.

But enough about me. Here’s the good news for you:

There’s one tool I used to change my life, and it can change yours, too. It’s called the Effective Feedback Cycle:

But before you dive in with both feet, you first must accept that you aren’t perfect. You have to put your ego aside.

As high performers, we have an unfailing drive within us to move forward, to improve, to grow. While that’s a very positive quality, it can also lead us to shove problems under the rug—just so we can keep our momentum going.

That’s why we all need to regularly take a deep breath and examine our Effective Feedback Cycle.

I didn’t create this cycle, but it’s a simple, highly visual way to move from the recognition of a problem through feedback and resolution.

Let’s walk through each step in the cycle, using myself as an example. You can use these same steps to help you identify and solve your own problems—both personal and professional.

- Discover the problem/issue

Without this initial step, the rest of the cycle doesn’t work. In fact, there’s no point in having a feedback cycle if you’re unwilling to see your own shortcomings.

I recommend two ways to dive into this. The first is via self-discovery. This often takes the form of meditation, focusing on negative emotions and/or the problem itself. If you focus on the problem—instead of running away from it—you will likely be able to clearly define what it is.

If, however, you’re completely lost, meditation can also guide you to the root of negative emotion. By removing external distractions and spending 5-10 minutes in a quiet space lingering with your negativity, you will uncover a lot of the triggers and root causes. The key is to “face and follow”—face the emotion and follow the triggers that make it worse or better. Several of these short meditation sessions will reveal much about what your problem actually is.

Self-discovery, however, is not the only path to defining a problem. An outside perspective is always helpful—which is why I always advocate that high performers hire a coach sooner rather than later. An attentive coach will be able to see shifts in your mood and behavior, and even recognize your problems before you do. Their perspective and experience is invaluable, so be sure you hire someone who is willing to be upfront and honest about what they see.

I’ve long practiced meditation, but I fully admit it’s only part of what I need for clarity. Years ago, I hired a coach to “show me the mirror”—reflecting my faults, insecurities, and weaknesses back to me so I could finally see them clearly. It wasn’t fun, but it was absolutely necessary for me to figure out a path forward.

- Analyze causes and consequences

Now that you have the problem defined, let’s map out your journey. Let’s assume that your present “problem state” is point B. You want to get to point C, where the problem is resolved. But you also know that to get to point B, you needed to start at point A.

So “face and follow” the path back to point A. What caused the problem you’re currently dealing with?

For me, my lack of vision, goals, and purpose really derailed me. I messed around with alcohol to hide the fact that I wasn’t going anywhere. But alcohol wasn’t the problem—nor was partying or staying up too late or eating junk. Those were all symptoms of a bigger problem: That I hadn’t put any effort into figuring out what I wanted in life and how to get there. And instead of putting effort into defining these critically important things, I just distracted myself with empty activities and indulgences. These just built on my existing anxiety and made my going-nowhere problem worse.

- Create options and solutions

Every problem should have two solutions. But before we start mapping out those fixes, we need to educate ourselves.

Why is it that we landed in our current situation? Who else has faced our problem? What insight or wisdom can they offer? Are there articles online we can read about it?

More than likely, the problem you’re facing has been faced by others before you. And in the digital age, it’s likely that one of them (at least) has documented their own journey of problem-discovery through solution and resolution. Look for these materials. Reach out to others who have found solutions to similar problems. With this research as a foundation, you can devise your own two solutions.

Now you’re probably asking: Why two?

Because not all well-researched solutions will work. Don’t give yourself the chance to give up on self-improvement just because of a single hiccup. With two solutions, you can move straight from solution A (if it doesn’t work) to solution B.

When I finally started paying attention to my own shortcomings and mistakes, I knew I needed a lot of help mapping out a way forward. So I challenged myself—with the help of a coach—to network with people who had done what I wanted to do (start my own business). I learned from their mistakes and successes so that I could take steps I knew would work.

It was around this time that I also started researching success routines and techniques. I discovered the Stoics, and really began to internalize their teachings—especially their lessons on mindfulness, taking full advantage of the hours in a day, and the necessity of working outside your comfort zone.

This two-pronged approach allowed me to grow in two different ways at the same time—with one approach complementing the other. There were certain very practical things that my high-performing contacts taught me that the Stoics couldn’t and vice-versa. Both together, however, were key to my ultimate success.

- Commit to action

As I have preached many times, “Action beats anxiety.” Once you have a solution in place and a plan to implement that solution, then act with resolve. Find accountability partners—actually business partners, perhaps, or colleagues/friends—who can check to make sure you’re following through on your “solution roadmap.”

A big part of this is routine. If you create a routine (or tweak an existing routine to accommodate your solution), you will start to build habits around daily action steps. If you know you have a strong routine in place, then weave this new solution into it.

My routine has been set for years, and has built high-performance habits that are now second-nature. I exercise daily, meditate or reflect daily, practice daily gratitude, and constantly revisit the steps I need to take to achieve my biggest goals. This roadmap to success is central to my Perfect Life Formula, which I’m now able to share with thousands of high-achievers all over the world.

- Evaluate performance

As you follow your “solution roadmap,” make sure to take pitstops to review your performance. Is your solution working? Does it really address your problem, or is it just another thing you’re doing every day? If you want, you can even create a rating scale to track progress and effectiveness.

This is where a coach really becomes valuable. Not only are they someone who provides accountability—someone you desperately do not want to disappoint—but they regularly ask you questions about how your routines, habits, and techniques are moving you toward your biggest goals.

My accountability is both public and private—I’m regularly sharing my progress with my workshops participants, my fellow coaches, and readers like you. This keeps me in a state of constant evaluation. I ask myself daily if what I’m teaching and preaching is actually working; if it isn’t, I scrap it and find a better approach.

#

See how easy that is? Five steps and I went from drunk jerk to successful friend, mentor, and coach. If I can turn my life around that dramatically, so can you.

Just remember: Whatever your high-performance goals may be, you’re likely to face problems. Don’t sweep them under the rug or ignore them. Use the Feedback Cycle to turn those problems into massive success stories—then pay that success forward by sharing your experience with other entrepreneurs.