There will only be a couple Top 10’s this week due to vacation

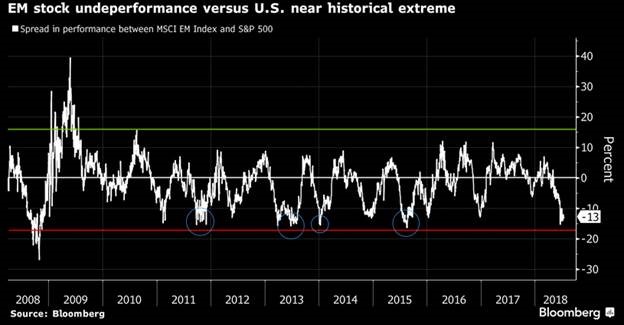

1.Emerging Markets Stock Underperformance Versus U.S. Near Historical Extremes.

Goldman, BlackRock and Franklin Templeton all say now’s the time to buy emerging markets – “The performance of emerging-market equities relative to U.S. large caps, as measured by the spread of rolling three-month returns, is near a threshold of -17 percent, which hasn’t been breached since the global financial crisis”

From Dave Lutz at Jones Trading

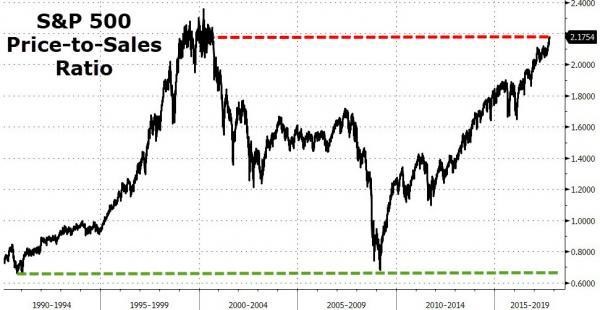

2.S&P 500 Price to Sales Ratio Touching 1999 All-Time Record Highs.

https://www.investing.com/analysis/weekly-sp-500-chartstorm–overbought-and-overhyped-200218865

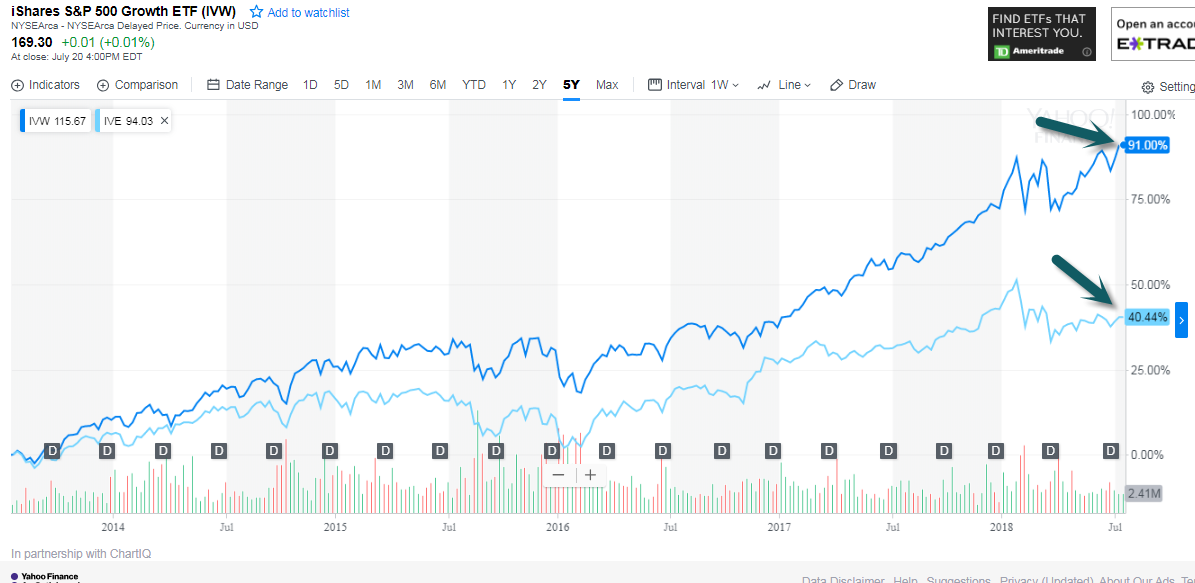

3.The Spread Between S&P Growth vs. S&P Value is Wider than when Fama and French Published their Famous Research…WOW!

Using Morningstar data, as of May 3, 2018, the iShares S&P 500 Growth ETF (IVW) had a P/B ratio of 4.7, and the iShares S&P 500 Value ETF (IVE) had a P/B ratio of just 2.0—the spread has actually widened from 2.1 to 2.4. Thus, value stocks are cheaper today, relative to growth stocks, than they were shortly after Fama and French published their famous research.

http://www.etf.com/sections/index-investor-corner/swedroe-value-premium-lives?nopaging=1

IVW Growth ETF vs. IVE Value ETF

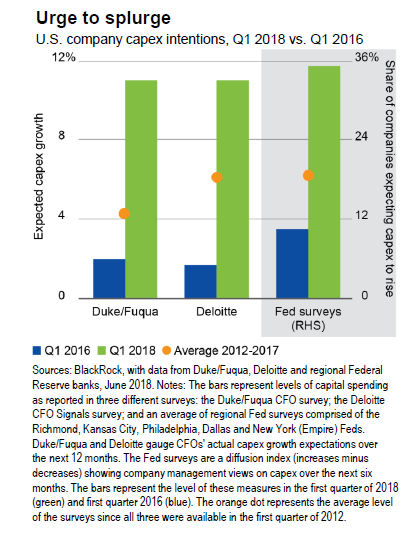

4.More on Capex….Companies Ramping UP Capex After Tax Cuts.

BLACKROCK

https://www.blackrockblog.com/

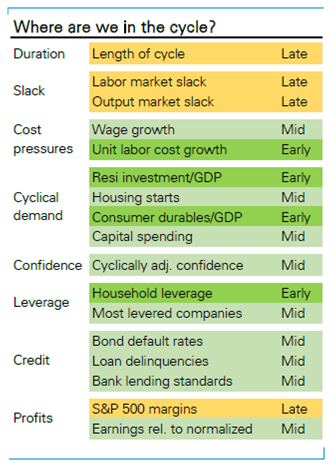

5.Interesting Grid From Torsten Slok on Where the U.S. Stands in Cycle.

Binky: How Late Is The Cycle?

Open report

– Equities typically fall into a bear market around recessions, with the S&P 500 down a median -21%. So 9+ years into the current recovery, market attention is keenly focused on how late the cycle is. Are margins and earnings peaking? Is the flattening 2s10s yield curve pointing to an imminent recession?

– What do fundamental metrics indicate as to how advanced the cycle is? The long duration and measures of slack in the labor and output markets unambiguously suggest the cycle is very late. By contrast almost all other indicators, ranging from inflation or cost pressures generated by that limited slack, the cyclical components of demand (housing; durables; and investment spending), confidence, corporate and household leverage, delinquencies and default rates, bank lending standards, margins and earnings, all suggest mid- or in some cases even early-cycle.

– The “late” cycle phase when slack is limited can go on for quite long. Limited slack by itself does not end the cycle. What does is either cost pressures that it generates or stretched spending, leverage, overconfidence or other excesses that it has historically coincided with. None of these currently appear to be in place. In the last 3 cycles, the late cycle phase lasted 2-4 years which in the current context would put the next recession potentially as far out as 2021. With core inflation having fallen short of the Fed’s target for 10 years, we expect it to continue to emphasize symmetry around its target and welcome not fret moves above 2%, sticking to its current guidance, possibly moving it up modestly. Moves up in the labor force participation rate, an increase in productivity growth and a higher dollar, all of which are elements of our baseline view, would act to lengthen the cycle.

– Getting out early can be costly. Average market returns during the late-cycle phase have not been particularly different from the mid-cycle phase. So historical ex-recession annual price returns of 12% are a reasonable indicator of potential returns in this phase. The timing of the move from late to end cycle is always unclear in real time and if the cycle goes on for longer would imply significant foregone returns amounting for example to median cumulative 42% during the late cycle phase of the last 3 cycles.

———————————————–

Let us know if you would like to add a colleague to this distribution list.

Torsten Sløk, Ph.D.

Chief International Economist

Managing Director

Deutsche Bank Securities

60 Wall Street

New York, New York 10005

Tel: 212 250 2155

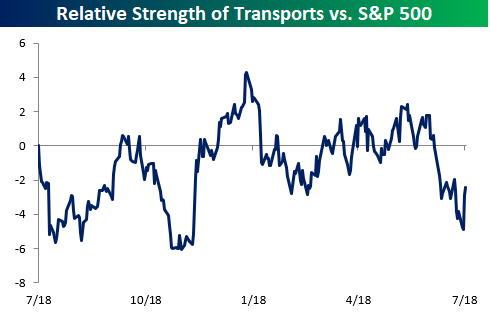

6.Dow Transports Below Highs and Showing Weak Relative Strength Versus the S&P…..Bull Needs Transports to Rally.

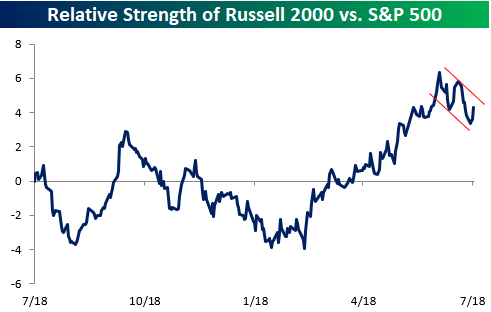

What Happened to the Transports and Small Caps?

Jul 19, 2018

When looking to get a handle on the overall health of the market, many technicians like to pay attention to Transports and Small Caps, but judging by the relative strength charts of the Dow Jones Transports and Russell 2000 versus the S&P 500, the broader market hasn’t been quite as strong. First, in the case of the Dow Transports, the index hasn’t been much of an outperformer at any point in the last year. Over the last month, though, the Transports have been extremely weak and are currently near their lowest level on a relative basis at any point in the last year.

The performance of small caps versus the S&P 500 has been a lot stronger than the Transports, but even here, we’ve recently seen a bit of weakness in the group. From when the China tariffs were first announced earlier this year right up until mid to late June, the Russell 2000 was a steady outperformer. Over the last month, though, the Russell 2000 has been a laggard. Granted, the index got a bit ahead of itself in the run-up, but notwithstanding today’s bounce, for the last couple of weeks as the S&P 500 has been in rally mode, Transports and Small Caps have been left behind.

https://www.bespokepremium.com/think-big-blog/

7.Copper Close to 20% Off Highs.

Copper back to 2017 levels sitting on 200 day moving average.

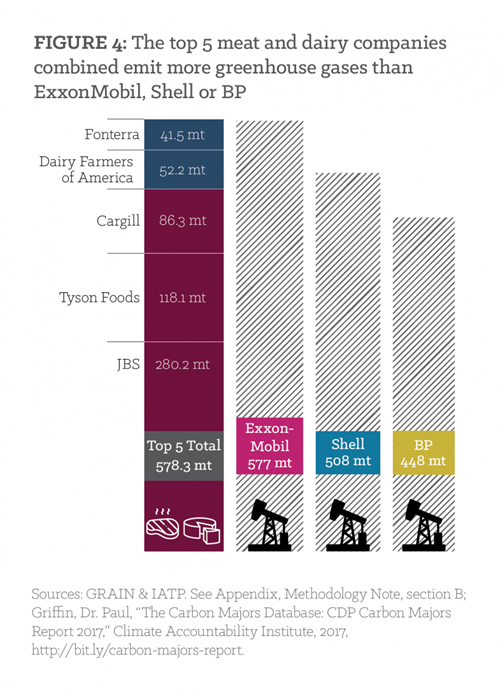

8.Meat and Dairy More Greenhouse Gas Emissions than Big Oil

Zerohedge

The report found out that the five largest meat and dairy corporations combined – JBS, Tyson, Cargill, Dairy Farmers of America, and Fonterra – are already responsible for more annual greenhouse gas emissions than ExxonMobil, Shell, or BP. According to one figure in the report, the combined emissions of the top five companies are on par with those of Exxon and significantly higher than those of Shell or BP.

9.Read of the Day…..Midlife crisis? It’s a myth. Why life gets better after 50

We don’t peak in middle age, say the experts. So forget about the stereotypes and embrace change

Jonathan Rauch

Beware midlife! You will be prone to sudden, disruptive upheaval. Around the age of 50 your productivity, creativity and adaptability begin their inexorable decline. With them, happiness ebbs. Your best years are behind you. Naturally, your job, marriage and shattered aspirations are to blame. If you or someone important in your life shows symptoms of midlife restlessness, be alarmed! The dashboard is flashing red.

Everything in the paragraph you just read is inaccurate. True, midlife is a tricky and vulnerable time. But most of what people think they know about midlife crisis – beginning with the notion that it is a crisis – is based on harmful myths and outdated stereotypes. The truth is more interesting, and much more encouraging.

1 You’re entering a danger zone

Actually, midlife is a time of transition. For most people, this is gradual, natural, manageable and healthy, albeit unpleasant. It is, in other words, the opposite of a crisis. The idea of the midlife crisis first appeared in an article by the psychoanalyst Elliott Jaques in 1965 and soon caught on in popular culture. Psychologists found no such phenomenon when they investigated, but the idea of the midlife crisis refused to fade.

Then, about 15 years ago, economists made an unexpected finding: the U-shaped happiness curve. Other things being equal – that is, once conditions such as income, employment, health and marriage are factored out of the equation – life satisfaction declines from our early 20s until we hit our 50s. Then it turns around and rises, right through late adulthood. This pattern has been found in countries and cultures around the world; a version of it has even been detected in chimpanzees and orangutans.

We assume that ageing, in and of itself, has either no effect on happiness, or that it simply makes us miserable. But instead, it fights happiness until midlife, then switches sides. Of course, ageing is never the only thing going on. How satisfied you feel at any given time will depend on many things; but the independent effect of ageing is more than enough to make a noticeable difference, especially if the rest of your life is stable and smooth.

Importantly, ageing’s effect is not sudden and dramatic. It is slow and cumulative. I was a textbook case. In my late 30s, I noticed restless and dissatisfaction, as if neither my life nor my accomplishments amounted to anything worthwhile. The malaise grew gradually but persistently. It was seriously dispiriting by my mid-40s. Then, at around 50, my malaise began to lift, as gradually as it had come. Now, at 58, it is mercifully behind me.

2 I must be unhappy about something

Not necessarily. Often, midlife malaise can be about nothing. At the age of 45, I won one of the highest prizes in American magazine journalism, a National Magazine award. That, finally, brought fulfilment – for about 10 days. Then the malaise came back. Flailing for an explanation, I lit upon my career. Many days, I felt tempted to quit my job, just to get out of my rut.

Humans are quite bad at attributing the causes of our unhappiness, and mine was the result of the ageing process. Throwing my career into the wind wouldn’t have helped, and may have made matters worse. Fortunately, I was rational enough to avoid rushing for the exit. So are most people. Contrary to the American Beauty stereotype, most of us slog through a midlife slump without acting out, which is fortunate, because a slump can indeed become a crisis if it leads people to make impulsive and costly mistakes.

So what is the slump about? It seems to be the effect partly of natural changes in our values. We begin adulthood, in our 20s and 30s, ambitious and competitive, eager to put points on the scoreboard and accumulate social capital. In late adulthood, after midlife, we shift our priorities away from ambition and towards deepening our connection with the people and activities that matter most to us. In between, we often experience a grinding transition when the old values haven’t brought the satisfaction we expected, but the new values haven’t yet established themselves.

3 Midlife unhappiness is for low-achievers

Surely, if we are lucky enough to have put lots of points on the board by 40, achieving or surpassing our goals, malaise won’t strike? Wrong again. The most perverse effect of midlife malaise is that high-achievers are especially vulnerable. The reason is what researchers call the hedonic treadmill. To motivate us, youthful ambition makes us unrealistically optimistic about how much satisfaction success will bring. Later, when we meet a goal, our desire for status and success moves the goalposts. Despite our objective accomplishments, we are not as satisfied as we expected. We wonder, “How come I’m not happier?” As this cycle of achievement and disappointment repeats over time, satisfaction comes to seem forever out of reach.

High-achievers are particularly vulnerable precisely because they set so much store by accomplishment, and because they have so much to be grateful for. They often experience their dissatisfaction as unjustified and irrational: a moral failing. That makes them still more dissatisfied. Now dissatisfaction is bootstrapping itself, creating a self-propelled spiral.

None of this is to cast aspersions on building a business, earning a doctorate, having a family, or other admirable ambitions. Those things are well worth doing. Just remember that objective success provides no guarantee against subjective discontent and, indeed, can make it worse – until the aforementioned changes in our values make it easier for us to jump off the ambition treadmill.

4 At 50, my best years are behind me

This myth is one of the biggest causes of discontent, because we assume that if we are not fulfilled at 50, we never will be. In fact, the happiness curve shows that, other things being equal, the best in life is yet to come. As we traverse our 50s, 60s and 70s, ageing makes us more positive and equable, and less stressed and regretful. This so-called positivity effect even seems to provide some emotional armour against the negative effects of physical decline and ill-health. In 2011, a study led by the Stanford University psychologist Laura Carstensen concluded: “Contrary to the popular view that youth is the best time in life, the present findings suggest that the peak of emotional life may not occur until well into the seventh decade.”

The false assumption that we peak in middle age not only makes midlifers unnecessarily pessimistic; it also fuels the stereotype of the burnt-out, bitter elder, which in turns fuels age discrimination that leaves vast reservoirs of experience and creativity underused. In the US, studies find that people aged 55-65 are more likely to start companies than those aged 20-34, and that older workers are just as productive as younger ones (and increase the productivity of those they work with). But you would never guess this from the way we think and talk about ageing.

5 Midlife slump is something to be ashamed of

This is perhaps the most harmful misconception of all. Combine the false assumptions listed above, and the picture emerges of midlife crisis as an unjustified, self-indulgent form of acting out by fortunate people who should be more grateful. No wonder it has become a widely mocked cliche, something people tut-tut over. But the result is that millions of people who are working through a midlife transition do so in silence and isolation, afraid to talk about it, often even with their spouses, for fear of setting off a family panic or being told they need medication.

That needs to change. Isolation and shame compound the likelihood of instability and genuine crisis. Instead, people need support and connection. They need to know, and to hear, that they are passing through a perfectly normal and ultimately beneficial human transition.

The Happiness Curve: Why Life Gets Better After Midlife by Jonathan Rauch (Green Tree/Bloomsbury, £18.99). Order a copy for £16.14 at guardianbookshop.com

Since you’re here…

… we have a small favour to ask. More people are reading the Guardian than ever but advertising revenues across the media are falling fast. And unlike many news organisations, we haven’t put up a paywall – we want to keep our journalism as open as we can. So you can see why we need to ask for your help. The Guardian’s independent, investigative journalism takes a lot of time, money and hard work to produce. But we do it because we believe our perspective matters – because it might well be your perspective, too.

The Guardian has brought a number of vital stories to public attention; from Cambridge Analytica, to the Windrush scandal to the Paradise Papers. Our investigative reporting uncovers unethical behaviour and social injustice, that helps to hold governments, companies and individuals to account. This work is costly – often we can’t anticipate how a story will unfold, how long it might take to uncover, and whether we will face legal threats that attempt to stop us. But we remain committed to challenging and exposing wrongdoing where we think it is critical – through this we can, together, create meaningful change in the world.

If everyone who reads our reporting, who likes it, helps to support it, our future would be much more secure. For as little as $1, you can support the Guardian – and it only takes a minute. Thank you.

https://www.theguardian.com/society/2018/jul/21/midlife-crisis-myth-life-gets-better-after-50

10. How Productive People Compartmentalize Time to Get the Most Done

Carl helps people all over the world to achieve their maximum potential by becoming better organised and more productive. Read full profile

I’ve never believed people are born productive or organized. Being organized and productive is a choice.

You choose to keep your stuff organized or you don’t. You choose to get on with your work and ignore distractions or you don’t.

But one skill very productive people appear to have that is not a choice is the ability to compartmentalize. And that takes skill and practice.

What is compartmentalization

To compartmentalize means you have the ability to shut out all distractions and other work except for the work in front of you. Nothing gets past your barriers.

In psychology, compartmentalization is a defence mechanism our brains use to shut out traumatic events. We close down all thoughts about the traumatic event. This can lead to serious mental-health problems such as Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) if not dealt with properly.

However, compartmentalization can be used in positive ways to help us become more productive and allow us to focus on the things that are important to us.

Robin Sharma, the renowned leadership coach, calls it his Tight Bubble of Total Focus Strategy. This is where he shuts out all distractions, turns off his phone and goes to a quiet place where no one will disturb him and does the work he wants to focus on. He allows nothing to come between himself and the work he is working on and prides himself on being almost uncontactable.

Others call it deep work. When I want to focus on a specific piece of work, I turn everything off, turn on my favourite music podcast The Anjunadeep Edition (soft, eclectic electronic music) and focus on the content I intend to work on. It works, and it allows me to get massive amounts of content produced every week.

The main point about compartmentalization is that no matter what else is going on in your life — you could be going through a difficult time in your relationships, your business could be sinking into bankruptcy or you just had a fight with your colleague; you can shut those things out of your mind and focus totally on the work that needs doing.

Your mind sees things as separate rooms with closable doors, so you can enter a mental room, close the door and have complete focus on whatever it is you want to focus on. Your mind does not wander.

Being able to achieve this state can seriously boost your productivity. You get a lot more quality work done and you find you have a lot more time to do the things you want to do. It is a skill worth mastering for the benefits it will bring you.

How to develop the skill of compartmentalization

The simplest way to develop this skill is to use your calendar.

Your calendar is the most powerful tool you have in your productivity toolbox. It allows you to block time out, and it can focus you on the work that needs doing.

My calendar allows me to block time out so I can remove everything else out of my mind to focus on one thing. When I have scheduled time for writing, I know what I want to write about and I sit down and my mind completely focuses on the writing.

Nothing comes between me, my thoughts and the keyboard. I am in my writing compartment and that is where I want to be. Anything going on around me, such as a problem with a student, a difficulty with an area of my business or an argument with my wife is blocked out.

Understand that sometimes there’s nothing you can do about an issue

One of the ways to do this is to understand there are times when there is nothing you can do about an issue or an area of your life. For example, if I have a student with a problem, unless I am able to communicate with that student at that specific time, there is nothing I can do about it.

If I can help the student, I would schedule a meeting with the student to help them. But between now and the scheduled meeting there is nothing I can do. So, I block it out.

The meeting is scheduled on my calendar and I will be there. Until then, there is nothing I can do about it.

Ask yourself the question “Is there anything I can do about it right now?”

This is a very powerful way to help you compartmentalize these issues.

If there is, focus all your attention on it to the exclusion of everything else until you have a workable solution. If not, then block it out, schedule time when you can do something about it and move on to the next piece of work you need to work on.

Being able to compartmentalize helps with productivity in another way. It reduces the amount of time you spend worrying.

Worrying about something is a huge waste of energy that never solves anything. Being able to block out issues you cannot deal with stops you from worrying about things and allows you to focus on the things you can do something about.

Reframe the problem as a question

Reframing the problem as a question such as “what do I have to do to solve this problem?” takes your mind away from a worried state into a solution state, where you begin searching for solutions.

One of the reasons David Allen’s Getting Things Done book has endured is because it focuses on contexts. This is a form of compartmentalization where you only do work you can work on.

For instance, if a piece of work needs a computer, you would only look at the work when you were in front of a computer. If you were driving, you cannot do that work, so you would not be looking at it.

Choose one thing to focus on

To get better at compartmentalizing, look around your environment and seek out places where you can do specific types of work.

Taking your dog for a walk could be the time you focus solely on solving project problems, commuting to and from work could be the time you spend reading and developing your skills and the time between 10 am and 12 pm could be the time you spend on the phone sorting out client issues.

Once you make the decision about when and where you will do the different types of work, make it stick. Schedule it. Once it becomes a habit, you are well on your way to using the power of compartmentalization to become more productive.

Comparmentalization saves you stress

Compartmentalization is a skill that gives you time to deal with issues and work to the exclusion of all other distractions.

This means you get more work done in less time and this allows you to spend more time with the people you want to spend more time with, doing the things you want to spend more time doing.

Featured photo credit: Pexels via pexels.com

https://www.lifehack.org/789803/how-to-compartmentalize-time

Carl Pullein

Carl Pullein