1.Magnificent 8 Largest Cap Weightings in S&P Skewing Fundamental Measures.

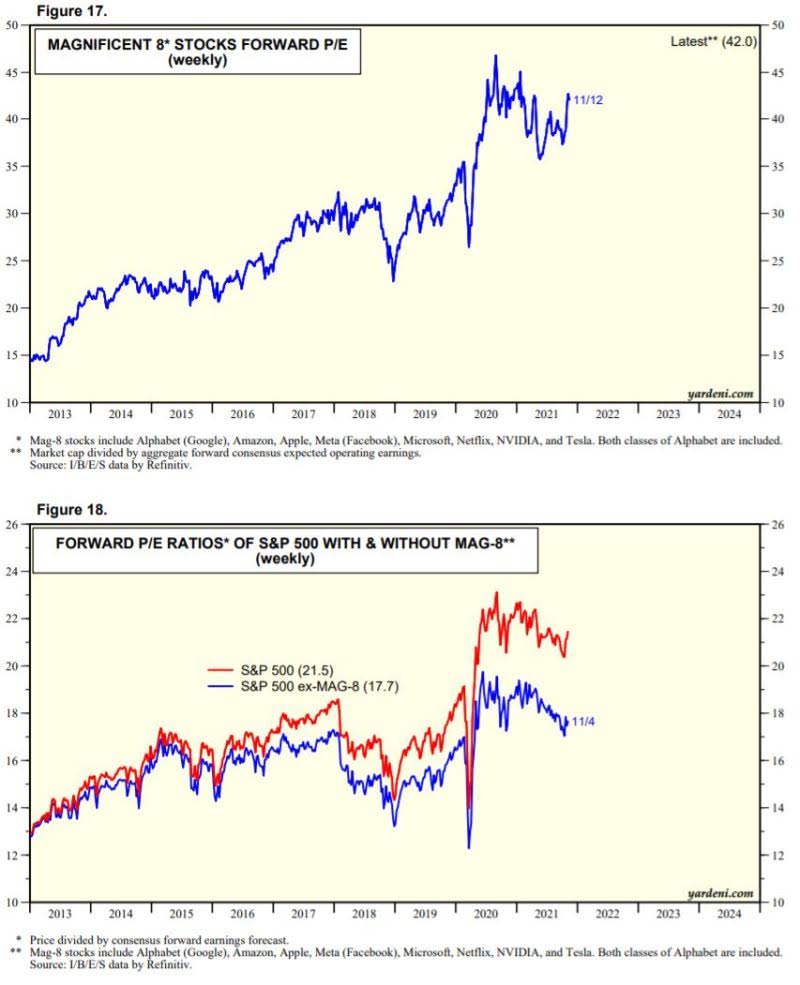

YARDENI RESEARCH. The Magnificent 8 are the eight stocks in the S&P 500 with the highest market capitalizations. They are Alphabet (Google), Amazon, Apple, Meta (Facebook), Microsoft, Netflix, NVIDIA, and Tesla. They are all in the S&P 500 Growth index. Collectively, their market cap has soared from $1.2 trillion at the start of 2013 to a record $12.0 trillion during the November 5 week. Over this same period, their market-cap share of the S&P 500 has risen from 8.9% to a record 30.0%.

Their forward P/E was about 15 in early 2013. Since mid-2020, it has been volatile around 40. The forward P/Es of the S&P 500 with and without the Mag-8 currently are around 21 and 18.

Our conclusion: LargeCaps are not overvalued excluding the Mag-8, which may be fairly valued too given their superior ability to grow their earnings.

https://www.linkedin.com/in/edward-yardeni/

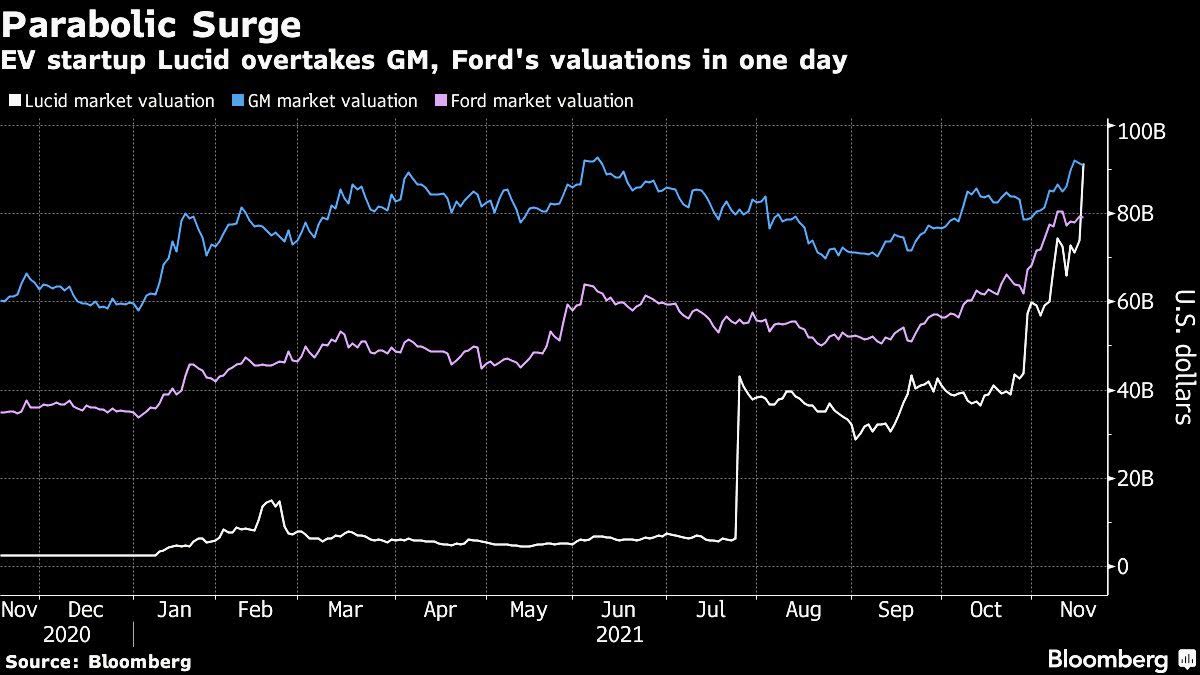

2.EV Startup Lucid Overtakes GM an F Valuation in One Day

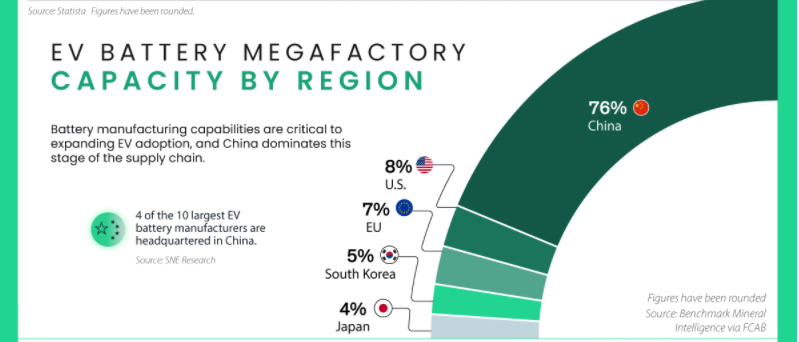

3.Visualizing the Global Electric Vehicle Market

VisualCapatalist The following content is sponsored by Scotch Creek Ventures.

https://www.visualcapitalist.com/visualizing-the-global-electric-vehicle-market/

4.Investment Grade Bonds -2% in 5 Days.

LQD chart 3rd lower low and 3rd pullback to 200day Since October.

5.Breakdown of CPI Report.

Charlie Bilello @charliebilello

Here’s a breakdown of price increases in the latest CPI report:

- Gasoline: +49.6%

- Gas Utilities: +28.1%

- Used Cars: +26.4%

- Meats/Fish/Poultry/Eggs: +11.9%

- New Cars: +9.8%

- Electricity: +6.5%

- Overall CPI: +6.2%

- Food at home: +5.4%

- Food away from home: +5.3%

- Transportation: +4.5%

- Apparel: +4.3%

- Shelter: +3.5%

https://twitter.com/

6.Crypto….43% of Men 18 to 29 Have Invested.

https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/11/11/16-of-americans-say-they-have-ever-invested-in-traded-or-used-cryptocurrency/ft-2021-11-11_cryptocurrency_02/

7.Wages Accelerating for Lower Income Workers.

Liz Ann Sonders Schwab

https://www.schwab.com/resource-center/insights/content/market-perspective

8.Vaccination by Country

From Dave Lutz at Jones Trading

9.Russian’s Astronauts on Space Lifeboat.

MorningBrew

| SPACE |

| The most dangerous thing in space right now isn’t aliens or cowboy Bezos—it’s more than 1,500 pieces of trash from a Russian satellite that was obliterated yesterday, which forced seven crew members on the International Space Station (ISS) to take shelter in space’s version of a lifeboat.

What happened: In an antisatellite (ASAT) missile test Monday morning, Russia blew up its own satellite, creating a cloud of space debris that careens by the ISS every 90 minutes. The US State Department called Russia’s actions “dangerous, reckless, and irresponsible,” and NASA said the explosion will “significantly increase the risk to astronauts and cosmonauts” aboard the space station. Some background: Antisatellite missile tests have been around since the dawn of the space race (the US launched the first one in 1959), but Russia, the US, China, and India have never used them against each other’s satellites. Still, these tests are usually considered “political moves” for countries to show that they could mess up your satellite if they wanted to. In space, blowing things up doesn’t make them go away There are currently millions of pieces of space debris—many from past missile tests—orbiting Earth at about 22,000 mph, and they pose significant risks for satellites that are critical for American military operations and a number of everyday commercial activities here on Earth, like banking and GPS.

Bottom line: As an increasing amount of economic activity relies on objects in orbit, space trash is bad for business.—MM |

https://www.morningbrew.com/

10. 9 Common Traits In The Lives Of Stoic Leaders-The Daily Stoic

By: Stephen Hanselman

For I believe a good king is from the outset and by necessity a philosopher, and the philosopher is from the outset a kingly person.” — Musonius Rufus, Lectures, 8.33.32–34

Stoic ethics were grounded in rejecting the valuing of external things and focusing instead on valuing our reason and choices in the pursuit of virtue (arete, or human excellence) alone. Their emphasis on the building of character left shining examples in the lives of the great Stoic leaders, who continually strove to have their traits of character reflect the four cardinal virtues of temperance (sophrosune), co

Good Judges of Value

“The wise man knows exactly what value should be put upon everything.” — Seneca

The first characteristic of great Stoic leaders is that they are excellent judges of the value (axia) of things.

Zeno of Kition, the founder of the school, had learned this great lesson from Crates of Thebes, the Cynic philosopher who was a student of Diogenes of Sinope. Diogenes’ father oversaw the minting coins in his native land, and he devalued the currency by reducing the actual content of silver in them. This earned Diogenes and his family an exile that brought him to Athens where Diogenes turned an insight about the true worth of currency into a core philosophical principle—that we should never grant more value to something than it is really worth. Zeno built Stoicism on this fundamental idea that the worth of external things is never greater than the moral worth of our own character.

Centuries later Epictetus, the former slave turned one of Stoicism’s greatest teachers, would continue to emphasize this core character trait with his students. He taught his students that with every impression we should think of ourselves as an assayer—one who is testing a coin for its actual precious content. The word he used repeatedly for this testing of impressions was dokimazein (to assay, or check the quality of the mineral content of coins). A skilled merchant, he would say, could toss a coin on the table and simply hear the difference between something of real value and a fake—just like a musician immediately spots the sour note in a performance.

That internal assayer, what Epictetus called our ruling reason (hegemonikon, the ruling part), was essential for everyone and most especially for leaders. What we choose to value, how much importance we assign to things, determines where we direct our activity and the results that follow. Bad leaders fail at this most fundamental task, which is why Epictetus put it like this:

“When it comes to money, where we feel our clear interest, we have an entire art where the tester uses many means to discover the worth…just as we give great attention to judging things that might steer us badly. But when it comes to our own ruling principle, we yawn and doze off, accepting any appearance that flashes by without counting the actual cost.”

Great leaders don’t get worked up by every impression, good or bad, that flashes on their radar. Instead, they take the time and all means necessary to test the actual truth and worth of the matter at hand. Soundness of judgment depends on this.

Sound Aim and Preparation

“What is quite unlooked for is more crushing in its effect, and unexpectedness adds to the weight of a disaster. The fact that it was unforeseen has never failed to intensify a person’s grief. This is a reason for ensuring that nothing ever takes us by surprise. We should project our thoughts ahead of us at every turn and have in mind every possible eventuality instead of only the usual course of events.” — Seneca

Also under the virtue of practical wisdom (phronesis), the Stoics tried to develop soundness of aim (eustochian) and careful preparation. Antipater, the fifth leader of Stoic school, used the image of an archer to talk about how a good leader goes about their work. After assessing the true value (axia) of things, we must set our aim correctly on something of true worth—for ourselves and for others in our care. This requires great training and practice, and just like an archer who spends much time and effort to develop a good aim, they also work to learn all the external factors of wind, temperature, humidity, which aren’t in anyone’s control and can affect whether we hit the target or not. Preparation in all these areas increases our chances of hitting the target.

Even so, we often will miss the target—sometimes by a lot. Preparation isn’t only about getting the skills needed to succeed, it’s also about contemplating failure in advance. A good leader spends time preparing for the worst as well.

Seneca was an ardent practitioner of premeditatio malorum, the premeditation of bad things. He urged us to always do the same:

“Here’s a lesson to test your mind’s mettle: take part of a week in which you have only the most meager and cheap food, dress scantly in shabby clothes, and ask yourself if this is really the worst that you feared. It is when times are good that you should gird yourself for tougher times ahead, for when Fortune is kind the soul can build defenses against her ravages. So it is that soldiers practice maneuvers in peacetime, erecting bunkers with no enemies in sight and exhausting themselves under no attack so that when it comes they won’t grow tired.”

After Seneca, Epictetus would talk about the need for a “hard winter training” (cheimaskesai), like Rome’s soldiers would practice when on break from the battlefront in Winter. Epictetus had learned physical disciplines that build character from his teacher Musonius Rufus, who practiced similar deprivations and hardships to build his resilience. Our aims, skill development, and constant review of what can go wrong–all of this is preparation: “We must undergo a hard winter training and not rush into things for which we haven’t prepared,” Epictetus urged his students.

If we don’t prepare for the worst, the Stoics teach, we simply aren’t prepared.

Shrewdness and Ingenuity

“If anyone can refute me—show me I’m making a mistake or looking at things from the wrong perspective—I’ll gladly change. It’s the truth I’m after, and the truth never harmed anyone. What harms us is to persist in self-deceit and ignorance.” — Marcus Aurelius

When Arius Didymus, one of the two Stoic advisors to the emperor Augustus, wrote about the various aspects of the virtue of wisdom (phronesis), he included two facets that really stand out: shrewdness (anchinoian, a readiness of mind, quick wittedness) and ingenuity (eumachanian, inventive skills, problem-solving prowess). Stoic wisdom wasn’t up in the clouds. It was more about the practical knowledge that would immediately let you know what to do and avoid, and, when stuck, how to work your way out of the situation.

Aristo, one of the early rebels in Stoicism, was one who highlighted the trait of shrewdness the most—he believed in throwing out all the rulebooks and that a well-prepared Stoic would simply immediately know what to do. The right course of action would just pop into his head. Just like a sea captain facing a great wave, a leader won’t go running to the ship’s manual for guidance in a pinch. But in the real world, things play out over a longer period of time and get a lot more dicey and difficult than that, and so orthodox Stoic teaching always used a lot of practical rules and reminders, including stories of great exemplars in difficult situations, to help cultivate the ingenuity that would help navigate tough seas.

Aristo was tricked by Persaeus, the student and personal scribe to Zeno, who had one twin brother deposit a sum with Aristo and later sent the other twin to collect the money. When Aristo discovered he had given the money to the wrong brother, and that Persaeus had refuted his claimed infallibility, he was dumbstruck. Shrewdness always needs the balance humility.

Marcus Aurelius taught that we should keep all our decisions and actions “under reservation” (hupexhairesis), meaning that whatever judgments we’ve made and course we’ve steered, we have to be ready to annul that judgment and set a new course if circumstances prove our initial assessment incorrect. A good leader is always ready to admit they are wrong, and, as Marcus wrote to himself, no one has ever been harmed by the truth. Marcus always stove to maintain “the view from above,” something he got from Plato, to avoid being lost in the minutiae of the moment. The universe is change, and life is opinion, he wrote. We must be ready to revoke the opinions we hold that put us in a bind, especially when a truer opinion awaits our discovery. The ingenuity to do this is what turns obstacles into opportunities—not only for success in our endeavors, but for growth as a leader.

Tough on Themselves, Understanding of Others

“Be tolerant with others and strict with yourself.” — Marcus Aurelius

If humility helps increase the trait of ingenuity in us, the Stoics teach, we will always do better if we keep our focus on correcting our own conceitedness and self-deception, rather than focusing on the faults of others. Heraclitus, who had influenced Zeno and Cleanthes

This is one of the first traits the Stoics sought to cultivate under the virtue of self-control (sophrosune)—by learning to keep an eye on our own deceptions and errors first. And here the Stoics offer a simple program. First, be strict with your own fallibilities. Next, be more lenient with what you perceive as the failings of others. Great leaders are excellent at practicing these two things. Marcus would constantly remind himself:

“Whenever you take offense at someone’s wrongdoing, immediately turn to your own similar failings, such as seeing money as good, or pleasure, or a little fame—whatever form it takes. By thinking on this, you’ll quickly forget your anger, considering also what compels them—for what else could they do? Or, if you are able, remove their compulsion.”

That’s a great exercise for anyone with responsibilities for managing a group. When it comes time to needing to correct someone, Marcus always invoked kindness: “If someone is slipping up,” he wrote, “kindly correct them and point out what they missed. But if you can’t, blame yourself—or no one.” This is how philosophy should work in practice. As Seneca put it, philosophy is a way of scraping off our own faults, not railing at the faults of others.

Even when a reprimand or punitive action must be taken with someone in your care, there is a kind path. Epictetus loved to share a story about the Stoic governor of Crete and Cyrene:

“When Agrippinus was governor,” Epictetus would recount admiringly, “he used to try to persuade the persons whom he sentenced that it was proper for them to be sentenced. ‘For,’ he would say, ‘it is not as an enemy or as a brigand that I record my vote against them, but as a curator and guardian; just as also the physician encourages the man upon whom he is operating, and persuades him to submit to the operation.’ ”

Good Stoic leaders hold themselves to a higher standard, and when handing down judgments on others, they do it as curators, guardians, or as a doctor trying to save someone—never in anger or superiority.

Modesty in Speech, Dress, and Lifestyle

“How much more philosophical it would be to take what we’re given and show uprightness, self-control, obedience to God, without making a production of it. There’s nothing more insufferable than people who boast about their own humility.” — Marcus Aurelius

Another area of self-control (sophrosune) that shows in the character traits of Stoics has to do with modesty in speech, dress, and lifestyle. Zeno was famous for this, and Cleanthes was too. Both men avoided bragging about their accomplishments and would use self-deprecating humor to defuse situations. The early Stoics kept strict diets of simple fare and dressed only in the simplest clothing. Cleanthes was famed for not even wearing an undergarment!

Their modesty extended from speaking, to eating, to dress and lifestyle. This helped keep their focus on self-mastery by not giving in to the ornate ways of speaking, eating, dressing, and living that preoccupy the time, energy and resources of most people. How many meetings are about the power suits, scarves, and accessories of their attendees, rather than the substance of the conversations at hand? How many business lunches are about the gastronomical one-upsmanship and stories of other equally extravagant meals enjoyed in exotic locations?

A Stoic leader tries to avoid this. Having their focus on correcting their own faults first, and not being distracted by the lifestyles that others promote, they remain always in a position to consider only what is choice-worthy or what is to be avoided. This brings an orderliness and propriety to everything they do. When we think of great leadership, it always has the simplicity and elegance that comes from not being weighed down by all those other things.

Taming the Tongue: Listening More Than Talking

“Better to trip with the feet than the tongue.” —Zeno

This modesty in speech made Stoic leaders expert listeners. Zeno had said that we have two ears and one mouth because that’s the ratio of listening to speaking we should adhere to in life. He also said it was better to trip with the feet than with the tongue. Cato, whose words could move the entire senate and people of Rome, famously said that he would only speak when he was convinced what he was about to say wasn’t better left unsaid.

In Epictetus’ Encheiridion 33, he lays down a whole series of prescriptions for behavior, including remaining silent for the most part in meetings, and when speaking to use as few words as necessary. He also is noticeably clear on a point that many need to hear today—that we should avoid using foul language at all costs and reprimand anyone who may happen to lapse into it.

The Stoics also believed, especially with friends and family, in frankness (parrhesia). Their character prized free, open, and direct speech to address matters of importance. For the Stoics, part of building a character anchored in self-control is about removing coarse language and the kind of character and lifestyle that goes with it, and replacing it with a more constructive and helpful directness.

Kindness, Fellowship, and Fair Dealing

“Remind yourself that your task is to be a good human being…Then do it, without hesitation, and speak the truth as you see it. But with kindness. With humility. Without hypocrisy.”

For a Stoic leader, the virtue of justice (dikaiosune) shows itself in several related character traits. Broadly, the virtue meant knowing how properly apportion things as they are due. Even with respect to the gods, they saw our practice of justice showing itself in reverence and piety—giving the gods their due. Turning to people, they tried to develop kindness, as we have seen, as a balance to their own strictness with themselves. Related to kindness, they believed in honesty (chrestoteta), good fellowship (eukoinonesian) and fair-dealing (eusunallaxian) in business. All these facets of character were part of the Stoic conception of justice.

Antipater was the first Stoic to debate business ethics with his teacher, Diogenes of Babylon. Diogenes took a caveat emptor, buyer beware, position in terms of what needed to be disclosed in business transactions. Other than not breaking the law, Diogenes believed it didn’t matter what you left out for the other party to discover later. Antipater said that if your sewer system were broken on your house, the interests of the family buying it would obligate you to tell the truth. Why should your gain be the source of someone else’s financial ruin? Antipater believed that we can’t ever let our self-interest cause injustice to the interests of our fellow human beings.

Later, Hierocles would create a model of behavior that tried to make this insight a kind of Stoic Golden Rule. We should see our circle of concern or self-interest as connected to an ever-widening circle of the interests of others: our family, neighborhood, city, country, and world. No matter how far out on the circle we go, there is an unbreakable connection between our self-interests and the concerns of others. Consequently, we should always be working to draw these circles closer to us. We can begin at home, by treating family as we would our self, friends as we would family, fellow citizens as we would friends, and foreigners as fellow countrymen.

In our time, Jim Collins would talk about the concept of a Level 5 Leader—someone who is always taking the larger interests of the organization and its stakeholders into account in every decision and action they take. It’s a vision of a more just leadership that the Stoics worked hard to develop.

Marcus Aurelius himself, the most powerful Stoic who ever lived, looked to the lives of previous Stoics like Thrasea Paetus and Helvidius Priscus whose leadership

Bravery Is Serving The Common Good

“I’ll accept whatever happens. And because of my relationship to other parts, I will do nothing selfish, but aim instead to join them, to direct my every action toward what benefits us all and to avoid what doesn’t. If I do all that, then my life should go smoothly.” — Marcus Aurelius

In the many generations before Stoicism came to Rome, there was a strong tradition of conveying the virtue of bravery in more classic martial terms—just as soldiers will face terrible odds on the battlefield and endure the most difficult of conditions, so we should conduct ourselves in everyday situations no matter how difficult. By the time Panaetius had met Scipio Aemilianus, it was clear that the young leaders of Roman society needed something else. By this time, generals and magistrates had come to see their appointments as primarily means of winning personal honor and financial gain. A bravery framed only in a victor taking the spoils mentality was destroying Roman society, just as it is our own today. Panaetius knew that when dealing with what’s expedient in public life, it’s easy to get lost and do things which are cowardly and unjust. In his second book of his great work on duties, Concerning Appropriate Actions, he emphasized that when dealing with the expediencies of politics you must always keep justice in mind.

For this reason, Panaetius shifted his writings about bravery to focus on what he called megalopsuchia, the greatness of soul that young leaders needed. This shift moved the emphasis away from service to personal ends to the service of the common good. With this new focus on magnanimity, Panaetius also talked about mercy, kindness, and being helpful to others. He believed that everyone has an inborn desire to lead and serve, and that while we all can’t be the brave Scipio on the battlefield, we can use the virtue of bravery and perseverance (andreia) to serve others.

Nowhere is this shift toward magnanimity and a new kind of resilience for the common good better expressed than in the life of Panaetius’ student, Publius Rutilius Rufus.

Rutilius was a towering figure in his day. Serving with Scipio Aemilianus on the battlefield in Carthage and Numantia, his bravery was renowned. He began his public service and eventually became responsible for training Rome’s troops—revising the entire training regimen and vastly improving the quality and effectiveness of the Roman military. Marius, the great general who ended up serving as consul a record seven times, preferred the troops trained by Rutilius above all others.

Many young leaders would be happy to accept that kind of public personal honor as enough and keep their head down. Not Rutilius. He saw the nefarious means that Marius and his cronies used to gain office and siphon money from the state. When a Stoic sees something, they say something. This is true bravery. Rutilius launched an attack on Marius and on the equestrian class tax farmers who were bilking the Anatolian population of their money. In exchange for this greatness of soul aimed at correcting the injustices of the state, Rutilius himself was brought up on the same charges and convicted of them in a kangaroo court, stripped of his estate and exiled. The only dignity left to him was choosing the location of his exile, which he immediately made Smyrna—the very place he was wrongly-convicted of defrauding. The Smyrnans welcomed him with a grant of citizenship, which he denied while living happily among them. When Sulla superseded Marius and became dictator of Rome, he offered Rutilius a pardon and a return from exile, to which Rutilius replied “I would rather have my country blush for my exile than weep at my return.”

Rutilius learned well from Panaetius the full meaning of bravery—service for a larger, common good—and spent his last days in Smyrna writing a history of Rome and receiving prominent visitors like Cicero.

Character Is Fate

True good fortune is what you make for yourself. Good fortune: good character, good intentions, and good actions — Marcus Aurelius

Finally, Stoic leaders all exemplified an intense focus on character in carrying out their duties for the common good. They believed a good character was created by a pursuit of all the virtues in each of our actions. They didn’t let the power and fame of position distract or ruin this deeper work.

Marcus Aurelius, the most powerful leader of his day, put it best:

“Make sure you’re not made ‘Emperor,’ avoid that imperial stain. It can happen to you, so keep yourself simple, good, pure, saintly, plain, a friend of justice, god-fearing, gracious, affectionate, and strong for your proper work. Fight to remain the person that philosophy wished to make you. Revere the gods, and look after each other. Life is short—the fruit of this life is a good character and acts for the common good.”

By: Stephen Hanselman, co-author of The Daily Stoic: 366 Meditations on Wisdom, Perseverance, and the Art of Livingand Lives of the Stoics, which is available for pre-order and is set to release on September 29!