1. Q1 Asset Class Performance Summary-Bespoke Investment Group

https://media.bespokepremium.com/uploads/2021/04/033121-ETF-MatrixQ11.png

2. Bond Bullish Sentiment Falls to 34 Year Low

No Love for Treasuries-Barrons

Weekly Technical Review

Macro Tides

March 29: Sentiment toward Treasury bonds is about as sour as it can be. The percentage of bond bulls fell to just 20% last week, according to the weekly survey of bond traders by Consensus. This is in the bottom 1.7% of all surveys during the past 34 years. In the majority of occurrences [when the percentage of bulls dropped below 30%], a low in Treasury bonds was coincidental with the low in bullish sentiment. There were instances in which Treasury bond prices fell to a lower low after bouncing. In early 2018, bullish sentiment fell below 30%, and TLT [the iShares 20+ Year Treasury Bond exchange-traded fund] entered a trading range between 116.50 and 122.90 from February until July. TLT then dropped to 111.90 in November 2018. A lower low is expected in the next few months.

—Jim Welsh

©1999-2021 StockCharts.com All Rights Reserved

3. This Quarters Jump in Yields has only been Surpassed Twice in Last Two Decades

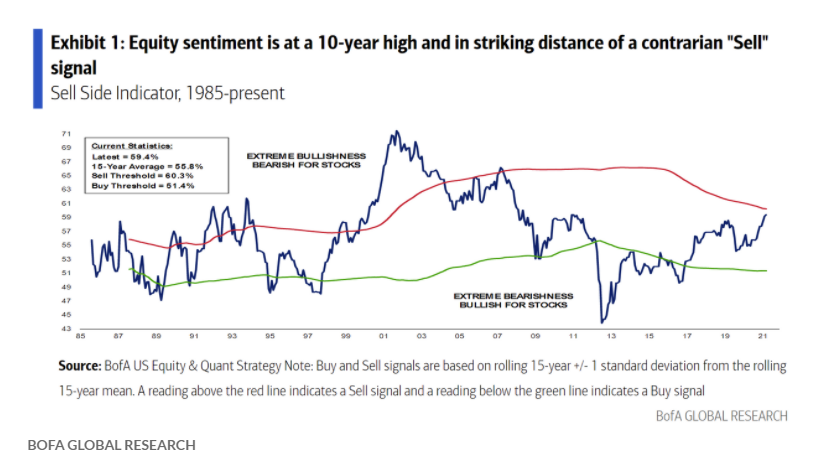

4. Sell Side Indicator Near 10 Year Highs but Still Below 2007 and 1999

‘Increasingly euphoric’ stock-market sentiment on verge of sending ‘sell’ signal

‘Increasingly euphoric’ stock-market sentiment on verge of sending ‘sell’ signal – MarketWatch

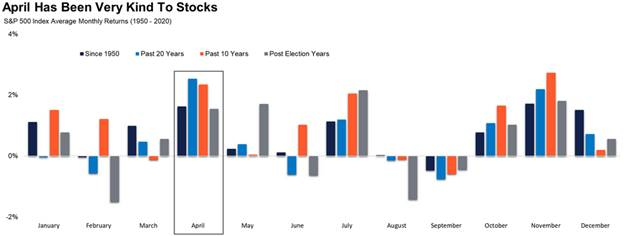

5. April is a Bullish Month…14 out of Past 15 Years

LPL notes that stocks have closed higher in April an incredible 14 out of the past 15 years

April is the second best month of the year for the S&P 500 (only November is better). Here’s what the average April does – Note the Majority of the gains happen the first 18 days

https://lplresearch.com/2021/03/31/stocks-love-april/

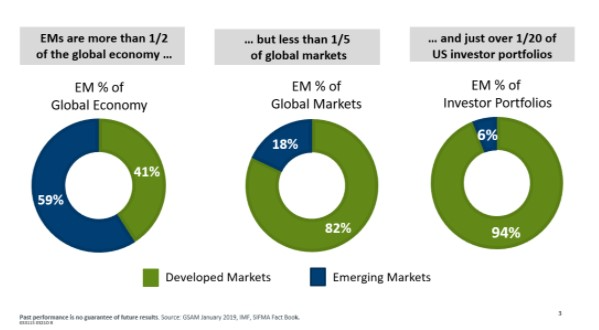

6. A Look at Emerging Markets Economies vs. Investor Portfolios

https://awealthofcommonsense.com/2021/03/animal-spirits-the-case-for-emerging-markets/

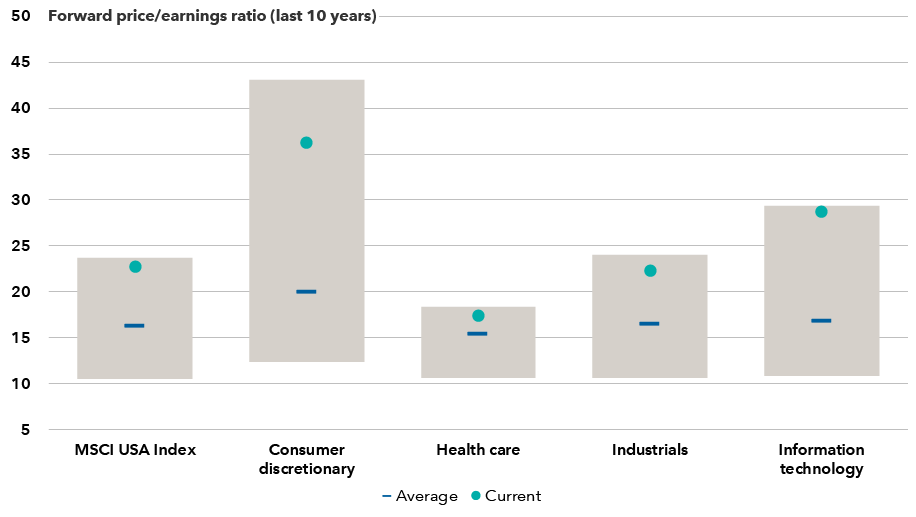

7. Valuations Across Industries

Valuations across most industries are high

Sources:RIMES, MSCI. As of 1/31/21.

8. The Future of Retail? Vermont Turns Macy’s into New High School for $3.5m

See inside a defunct Macy’s that underwent a $3.5 million transformation to become a high school in Vermont

Downtown Burlington High School is located in a defunct Macy’s store. AP Photo/Charles Krupa

- A high school in Burlington, Vermont moved into a defunct Macy’s store.

- The school district spent $3.5 million renovating the department store into classrooms.

- Some abandoned malls across the US are being repurposed for other uses.

- See more stories on Insider’s business page.

High school students in Burlington, Vermont are now attending school in what was once a Macy’s department store in a local mall, Lisa Rathke reported for the Associated Press.

Downtown Burlington High School. AP Photo/Charles Krupa

Students at the school spent the previous six months learning remotely after toxic chemicals that can have dangerous health effects, called PCBs, were found in the school building.

https://www.businessinsider.com/vermont-empty-mall-macys-is-used-as-school-2021-4

9. Sales of Bentleys and Lamborghinis are booming because rich people are bored

By Peter Valdes-Dapena, CNN Business

(CNN)It’s been a great time to be selling really, really expensive cars.

“I’ve been in this business 40 years and I’ve never seen it like this,” said Brian Miller, president of Manhattan Motors, a high-end dealership that sells Bentleys, Lamborghinis and Bugattis, among other ultra-luxury brands.

While auto sales as a whole have suffered from factory shutdowns and other disruptions due to the pandemic, sales of super-expensive cars, like Ferraris, Bentleys and Lamborghinis, finished 2020 at a blistering pace.

In the United States, overall passenger car sales were down 10% last year compared to 2019. Even as auto sales recovered strongly in the fourth quarter,they only just matched the pace seen in the fourth quarter of 2019, said Tyson Jominy, vice president for data analytics at J.D. Power.

But sales of cars costing more than $80,000 were almost double in the fourth quarter what they had been the year before. And for cars costing more than $100,000, sales in the US were up 63% that quarter, said Tyson Jominy, vice president for data analytics at J.D. Power.

“There’s a fairly fantastic wealth effect going on,” Jominy added.

Lamborghini had its second best year ever in 2020 in terms of sales and turned its highest profit ever.

The booming stock market has played a big part, he said. And since the wealthy haven’t been able to spend money on trips, many have turned to luxury goods, like expensive cars.

Customers oftenorder these cars to their exact specifications and wait months for them to be built, Miller said. But he often keeps some on hand to sell tothose who want to drive out in their new Rolls-Royce or Lamborghini that day. That’s just not possible right now, he said. He can’t keep the cars on the lot.

Miller credits the boom, in part, to people sitting around with not much else to do but look at expensive cars on the Internet.

One of the more remarkable things about the run-up in sales, said Jominy, is that it has been largely young buyers driving the wave. “[T]he rich Millennial tech employee in Austin is now the archetype,” he said.

Record sales and ‘instant growth’

Bentley, the 101-year-old ultra-luxury car brand, had its best year ever last year, despite the pandemic totally shutting down its factory in Crewe, England, for seven weeks. Even after the factory reopened, it was running at half its normal pace for nine more weeks, said Bentley CEO Adrian Hallmark in an interview with CNN Business.

McLaren’s new hybrid supercar has computer chips in its tires

Still, Bentley sold 11,206 cars and SUVs last year — just over 100 more vehicles than in 2019, which had already been a record year.

China was also especially big for Bentley, with sales there growing by about 50%, Hallmark said. The redesigned Flying Spur sedan was an especially big hit, he said. That model had been absent from the market while the factory changed over tothe new version, which came out at the end of 2019.

“When it came, it was like a desert that got rain and all the flowers popped up,” Hallmark said. “Instant growth with a product that is normally more than 30% of [Bentley’s] volume.”

Lamborghini, meanwhile, had its most profitable year ever in 2020 and its second best sales year in the brand’s history. Only in 2019 were more Lamborghinis sold. For the whole year, the exotic automaker sold 7,430 cars and SUVs, down 9.5% compared to 2019. But the last quarter of 2020 was the best in the Italian supercar maker’s history and its order banks are already filled for the first nine months of 2021, Lamborghini CEO Stephan Winkelmann said.

Both Bentley and Lamborghini are owned by Volkswagen AG (VLKAF).

Sales at Ferrari were down about 10% for the year, including a seven week factory shutdown. But the automakerset records for sales and revenue in the fourth quarter. Orders for future cars are also at record levels, the company announced.

Not all high-end automakers did so well last year, though. The timing of new product introductions, which don’t always align nicely with the calendar year, can have a lot do with it.

How Covid has changed the way used cars are sold

Rolls-Royce’s sales, for instance, were down more than 26% last year compared to a record year in 2019. That prior year, 2019, was the first full year of sales for the Rolls-Royce Cullinan SUV, one of the brand’s most popular models. By contrast, in 2020, Rolls-Royce’s factory stopped making the Ghost sedan for much of the year as it prepared for the new redesigned version.

Still, according to BMW, Rolls-Royce’s parent company, the order bank for Ghosts is full for most of 2021 and the company had record interest in its bespoke customization business last year.

Correction: A previous version of this article misstated the age of Bentley.

https://www.cnn.com/2021/04/01/success/luxury-car-sales-pandemic-2020/index.html

10. Waldenomics: Modern Lessons from Henry David Thoreau

By Jen McGivney | March 21, 2021 | 0

Henry David Thoreau hasn’t aged well, particularly since his death 159 years ago. Through modern eyes, the 19th century author looks like an out-of-touch dreamer, a privileged loafer. The guy who avoided a real career to live in a cabin in the woods now has his words relegated to hiking guides and inspirational notecards.

A counterpoint, if I may. Thoreau couldn’t be more relevant to this moment, to us. While his words lean idealistic, his professional life was far more pragmatic. Read in context—knowing what preceded his escape to the cabin and what followed it—Walden becomes a guide to professional reinvention. Considered a formative piece in the canon of American literature, the book has at times been described as a personal declaration of independence and a manual for self-reliance.

Consider this. Thoreau graduated from college as the country reeled economically from the Panic of 1837. Jobs were sparse; businesses were failing. New technologies changed how people lived, worked, and shared information. And around the world, people were catching a mysterious lung disease without a cure. Thoreau caught it, too.

It wasn’t an ideal time to ponder professional fulfillment, but economic uncertainty and a pandemic can compel one to rethink life choices.

While his Harvard classmates flocked to secure careers in finance and law, Thoreau explored his options. He became a teacher, but his stand against corporal punishment forced his resignation. The job in his father’s pencil factory? Meh. He worked as an editorial assistant, a job that brought him joy but no pay; he shoveled manure, a job that brought him pay but no joy. He struggled to be a freelance writer through all of it, as tricky an endeavor then as now.

By the time Thoreau went to the woods, he faced a question as devastating as it is ordinary: How can I make a good living while living a good life?

* * *

Walden is the book people love to hate. I get it. Here’s a single white guy without kids offering advice on how to live life well. Still, each time I read it, I cheer for him. Because of his tuberculosis, Thoreau knew his life wouldn’t be long, but insisted it would be interesting. His family was poor, and at Harvard, he fell behind in classwork each time he took breaks to earn tuition money. After he earned a prestigious degree with countless ways to monetize it, he remained insistent: He wanted to be a writer in a world that didn’t like to pay writers. Perhaps my sympathy is a side effect of my profession.

Walden isn’t an easy read. I get that, too. It’s only the weight of my book that prevents me from chucking it across the room during those meandering middle chapters. He ponders ants as they wrestle; he contemplates, at length, the depth of the pond. He’s got a lot to say about beans.

Henry David Thoreau’sWaldenis a controversial classic of early American literature.

But this isn’t a book about shunning money or success. Thoreau spent his two years by the pond grappling with the purpose of the first and the meaning of the second. It’s a book about creating a personal business plan. Thoreau titled his first chapter—his longest and most quoted—“Economy.” He wrote that he went to Walden Pond “to transact some private business” and to “acquire strict business habits.”

I’ve distilled his insight into a model I call Waldenomics. Waldenomics presents Thoreau’s five principles of business—the business of making a living—inspired by his time at the pond and developed during the years following it.

Waldenomics Principle 1: Redefine capital. You spend more than money; you spend your life.

“[T]he cost of a thing is the amount of what I will call life which is required to be exchanged for it, immediately or in the long run.” —Walden

If we think of currency as our energy and time—not just money—our measure of success changes. Know the literal price of things, Thoreau advised, but know their costs, too. It changes the math on big decisions, as a lucrative job can come with more price than profit if it robs one of all energy. A less-expensive house in the suburbs that brings a stressful commute has a price tag in hours as well as dollars.

Thoreau created a personal economic model that puts money in its periphery but maintains profit as its goal. If we trade in life, how’s our ROI?

Thoreau wasn’t a guy who disregarded money, however. Like many people who didn’t have much money as a child, he obsessed over it as an adult. In Walden, he listed his budgets down to the half-penny (seriously). These budgets revealed a shift: They began with his expenses, not salary. Lower expenses granted him greater professional freedom, “for a man is rich in proportion to the number of things which he can afford to let alone.”

Everything comes with a price, even—and perhaps especially—a career. Thoreau’s goal was to find a job that paid him more than it cost him.

Waldenomics Principle 2: Your passion doesn’t need to be your paycheck, but don’t let your paycheck destroy your passion.

“I have found out a way to live without what is commonly called employment… Indeed my steadiest employment, if such it can be called, is to keep myself at the top of my condition…” —Thoreau’s response to an 1847 Harvard alumni survey

Thoreau was no purist. The guy we know as America’s naturalist earned most of his money through surveying land for developers preparing to build roads and neighborhoods through forests.

During his thirties, after he left Walden Pond, Thoreau needed money. Lots. He owed a publisher $290—equivalent to a year’s salary—after his first book flopped. When his father’s pencil plant suffered a fire, he needed about $500 to recover. Thoreau did what many of us do. He sold out. But instead of hitting up a Harvard finance buddy for a job in New York, he found a well-paying job that kept him where he was happiest: in muddy boots in the woods with a notebook. Surveying, oddly, became the most Thoreau way to sell out.

Thoreau continued to fill journals with observations and essays about nature. One day, about two years after becoming a professional civil engineer, Thoreau took a walk around Walden Pond. He rested on an oak stump and realized he was at the site of his old cabin. There, he felt inspired to return to a project he put away years before. A book. The book.

Thoreau found a job that allowed him to stay “at the top of his condition,” where he was happy and where he could think big thoughts. He sold out, just enough, to buy his way back in.

Waldenomics Principle 3: Be willing to quit a good job. Beware a “dangerous prosperity” that distracts you from bigger goals.

“I left the woods for as good a reason as I went there. Perhaps it seemed to me that I had several more lives to live, and could not spare any more time for that one.” — Walden

We wouldn’t know Thoreau as a writer if his contemporaries hadn’t known him as a quitter. One woman, upon hearing about his Walden experiment, called him “a good-for-nothing, selfish, crab-like sort of chap, who tries to shirk the duties” of adulthood. Yet Thoreau didn’t job hop for lack of success. When he taught, he became one of the highest-paid and most beloved teachers in town. While at his father’s factory, he invented a graphite mill that revolutionized the industry and created the country’s finest pencil. He lived with his mentor Ralph Waldo Emerson as the tutor and caretaker of his children—an easy life in a beautiful home, but one he called “a dangerous prosperity” that distracted him from a greater calling.

Quitting a job to begin again can require greater perseverance than remaining loyal to the wrong one. Thoreau disregarded the accolades and criticism of others to work toward a higher, harder goal: earning his own respect.

Waldenomics Principle 4: Use technology selectively.

“We do not ride on the railroad; it rides upon us.” — Walden

“We do not use social media; it uses us.” — Thoreau today, probably

Thoreau has the reputation of a curmudgeon who hated technology. Not true. He had the mind of an engineer (remember his graphite mill?) and marveled at inventions. He didn’t want to just ride a train; he wanted to know how a steam engine worked. He despised, however, how mindlessly people adopted innovations as tools of distraction—how such smart things could come to such dumb ends.

In the mid-19th century, printing presses produced newspapers and magazines more cheaply than ever, and a glut of content followed. In Walden, Thoreau chided people who read the news multiple times a day yet barely noticed what was in front of them. When the trans-Atlantic telegraph was in development, he believed people thought more about using it than having anything meaningful to convey when they did.

Thank God he never saw Twitter.

Thoreau believed our lives are “frittered away by detail,” and those details distract us from the focus needed to think original thoughts, not merely react to reactions. The telegraph—or social media or television or video games—isn’t evil on its own, but prioritizing technology over ideas makes people “the tools of their tools.”

Waldenomics Principle 5: Feeling lost is a “memorable crisis.” Embrace it.

“Not till we are lost, in other words, not till we have lost the world, do we begin to find ourselves, and realize where we are…” — Walden

Thoreau loved liminal spaces. He found beauty where disparate things overlapped: one season against another, nature against civilization. He didn’t build his cabin in the wilderness; he built it two miles from town by the railroad. He sought solitude, but kept his door unlocked for friends who visited daily.

He thrived in the liminal spaces of life, too, when one chapter ended and the next hadn’t quite begun. These are the times we become most attuned to our true selves. Thoreau cringed at the “young men who had ceased to be young, and had concluded that it was safest to follow the beaten track of the professions.” His favorite people were like him, who didn’t suffer from uncertainty but found motivation in it, who thrived in liminal spaces.

The guy who shoveled poop for a paycheck recognized that not every day was a dream day at work. The guy who surveyed his beloved woods knew that money meant compromise. Yet Thoreau refused to associate adulthood with unquestioned allegiance to professional misery. He strived to remain a little lost, a little separate, and encouraged readers to do the same.

And then maybe, on an ordinary day—perhaps while resting on an oak stump—we’ll have space enough to notice the hint of a beginning, the start of a new liminal state, and realize we have another life to live, and can’t spare any more time for this one.

https://www.success.com/waldenomics-modern-lessons-from-henry-david-thoreau/

Lansing Street Advisors is a registered investment adviser with the State of Pennsylvania..

To the extent that content includes references to securities, those references do not constitute an offer or solicitation to buy, sell or hold such security as information is provided for educational purposes only. Articles should not be considered investment advice and the information contain within should not be relied upon in assessing whether or not to invest in any securities or asset classes mentioned. Articles have been prepared without regard to the individual financial circumstances and objectives of persons who receive it. Securities discussed may not be suitable for all investors. Please keep in mind that a company’s past financial performance, including the performance of its share price, does not guarantee future results.

Material compiled by Lansing Street Advisors is based on publicly available data at the time of compilation. Lansing Street Advisors makes no warranties or representation of any kind relating to the accuracy, completeness or timeliness of the data and shall not have liability for any damages of any kind relating to the use such data.

Material for market review represents an assessment of the market environment at a specific point in time and is not intended to be a forecast of future events, or a guarantee of future results.

Indices that may be included herein are unmanaged indices and one cannot directly invest in an index. Index returns do not reflect the impact of any management fees, transaction costs or expenses. The index information included herein is for illustrative purposes only.