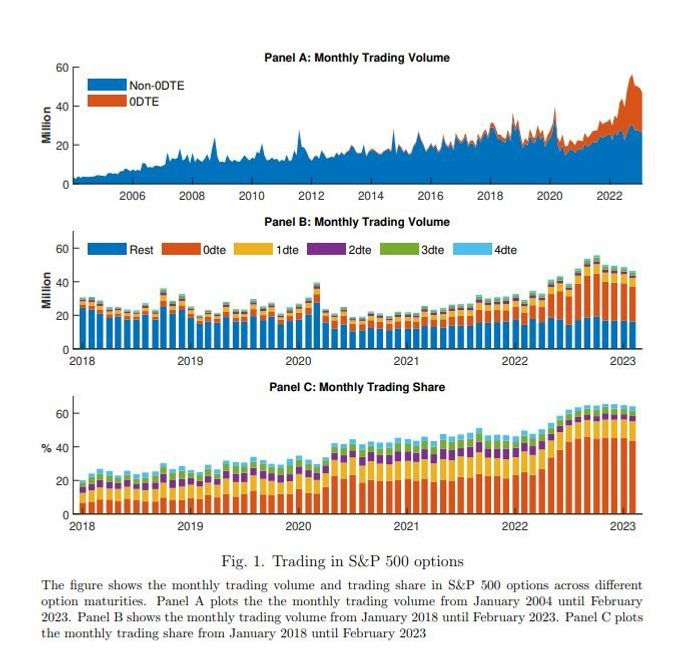

1. Retail Investors Losing Money Daily on Zero Dated Options

Marketwatch How popular have “0DTEs,” or option contracts with zero days until expiration become? The below chart, from a study by researchers at the University of Muenster, shows an explosion in the number of investors trying their hand in trading S&P 500 options from 2020 into this year.

UNIVERSITY OF MUENSTER

But beyond the chart are some unsettling numbers. The researchers note that between February 2021 and February 2023, retail investors lost $184,000 on the average day, but since the introduction of a daily expiration calendar in May of 2022 — meaning they can trade expiring options everyday — average losses have totaled $358,000 per day.

“We find that retail investors correctly take the expensiveness of 0DTE options into account when placing their orders, but that the substantial spreads charged by market makers lead to significant losses. Our study is a cautionary tale against unrestricted access to highly complex trading vehicles by investors who lack sufficient financial education,” said the researchers.

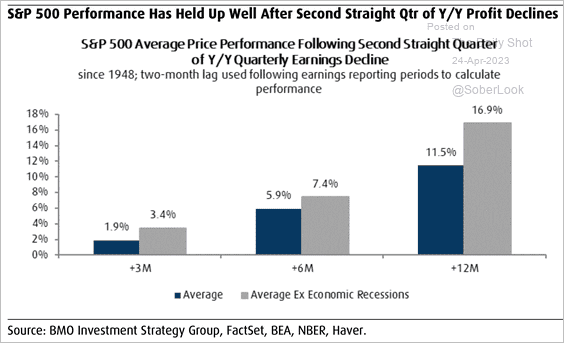

2. History of Two Straight Quarters of S&P Profit Declines

The Daily Shot A second straight quarter of year-over-year profit declines is not necessarily a headwind for stock prices.

Source: BMO; @SamRo, @TKerLLC

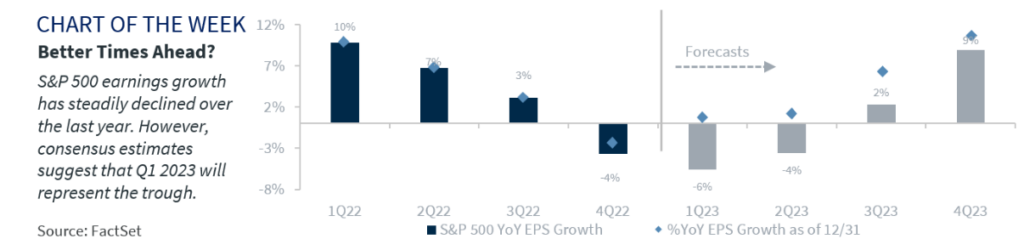

3. Is Q1 2023 the End of Declining Earnings?

Advisor Perspectives Tune Out The Noise and Short-Term Distractions by Larry Adam of Raymond James

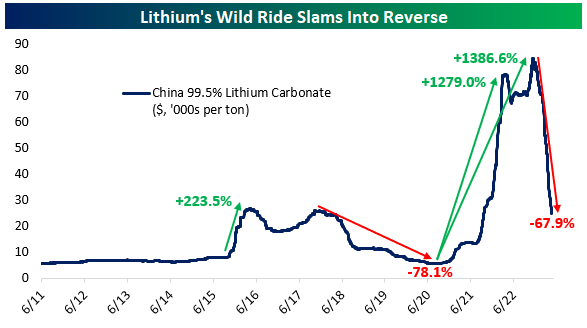

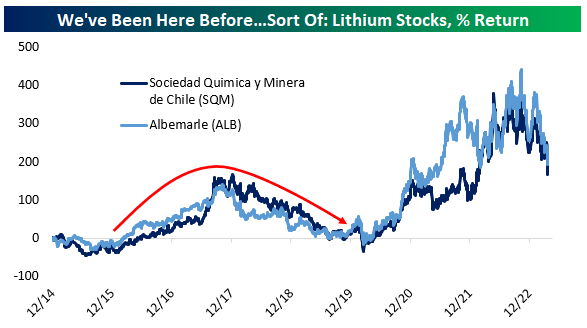

4. Lithium: The Cycle Continues

Bespoke Investment Group If you haven’t checked the price of lithium lately, you might be in for a surprise. Spot prices for lithium carbonate in China have collapsed by two-thirds since hitting record highs in November of last year. Prices have gone from $84k per ton to $25k per ton. That unwinds the vast majority of a spectacular surge that played out from 2020 to 2022. Lithium initially surged 1,279% from July 2020 to March 2022 as part of the broader explosion of commodity prices and booming demand for electric vehicles, eventually peaking up 1,387% from the post-COVID lows. It’s easy to forget that this critical battery input had already gone through one such cycle. A 224% rally in 6 months during late 2015 and early 2016 before a long, slow bear market that saw prices down 78% over several years.

In the equity market, the price cycle hasn’t been as dramatic in percentage terms, but there has still nonetheless been a double cycle of surging stock prices in 2016 followed by a grinding bear market, and then an even more dramatic surge through late 2022 that is now sliding into reverse. On Thursday, Chile’s government announced reforms to its lithium extraction policy. While existing contracts with firms that operate in the rich lithium brine deposits of the Chilean Atacama desert will be honored, the market is looking at weaker lithium prices and the fact that existing contracts will be replaced by less favorable ones 10+ years down the line and hitting lithium players. SQM is off 21% today while ALB is 10% lower.

Have you tried Bespoke All Access yet?

https://www.bespokepremium.com/interactive/posts/think-big-blog/lithium-the-cycle-continues

5. Russell 2000 Small Cap Stocks

50day about to cross below 200day to downside

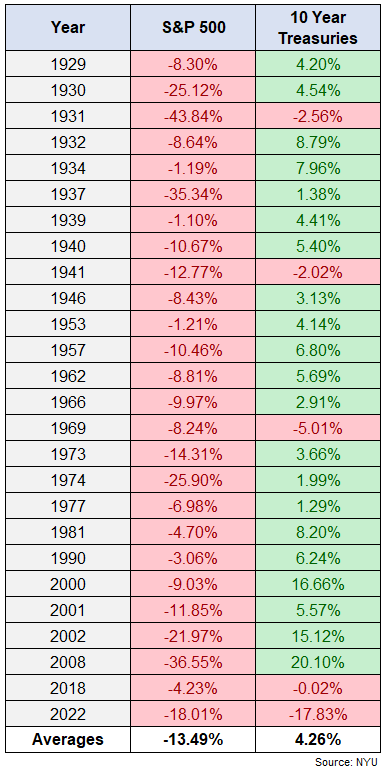

6. History of Treasuries When Stock Market Down.

A Wealth of Common Sense by Ben Carlson

https://awealthofcommonsense.com/2023/04/the-biggest-no-brainer-investment-right-now/

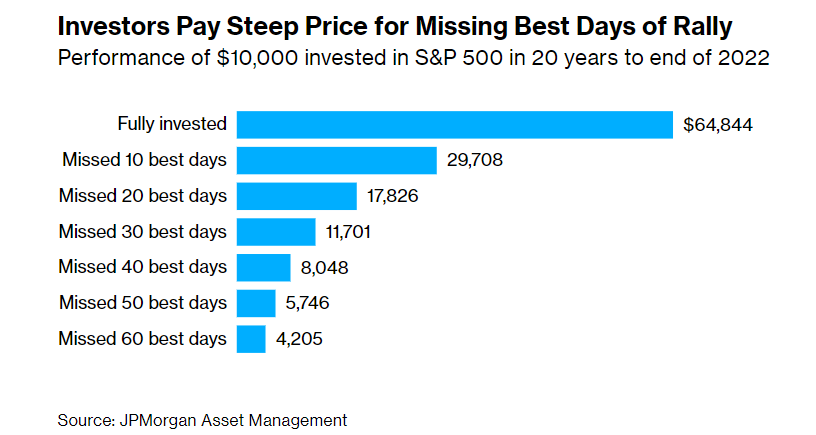

7. Fearful Millennials Missed Stock Market Rally With Shift to Cash-Bloomberg

· Getting out of stocks last year meant missing 2023 rally

· Other generations were more likely to stay put during rout

Millennials were more likely than any other generation to flee the stock market during last year’s rout. That meant they were also more likely to miss out on the subsequent rally.Those were the results of a survey released Monday by Ernst & Young’s wealth management unit, which found that nearly half of millennial respondents turned to cash amid the market volatility. By comparison, just 34% of Gen X and 24% of Baby Boomers sought safety in cash.

The survey of more than 2,600 clients was conducted from October to November, right around the time the stock market bottomed. Since its low on Oct. 12, the S&P 500 Index has jumped about 16%. Despite the stock rally, cash is increasingly in vogue. Vehicles like high-yield savings accounts, money market funds and certificates of deposit are offering attractive returns for the first time in years amid the Federal Reserve’s aggressive rate-hike campaign. Still, there’s plenty of debate over whether those products can compete against inflation and the stock market. There’s also downside to pulling money from stocks: JPMorgan Asset Management data show that investors who were absent for the S&P 500’s 10 best days in the two decades through 2022 received half the gains of those who were in the market for the entire period.

Investors Pay Steep Price for Missing Best Days of Rally Performance of $10,000 invested in S&P 500 in 20 years to end of 2022

Source: JPMorgan Asset Management

Baby Boomers are more likely than millennials to work closely with a financial adviser, which may have encouraged them to stay invested during the market volatility, said Mike Lee, leader of EY Global Wealth & Asset Management. They may also have a stronger stomach for market swings after watching past market recoveries, including the rebound after the 2008 financial crisis, he said.

EY Global Wealth & Asset Management found that more clients may flock to cash. “If volatility continues, a greater proportion of clients (43%) would further increase their exposure to savings and deposits,” the report said.

The survey used the following age definitions: Millennials (21-41), Gen X (42-57) and Baby Boomers (58 and over)

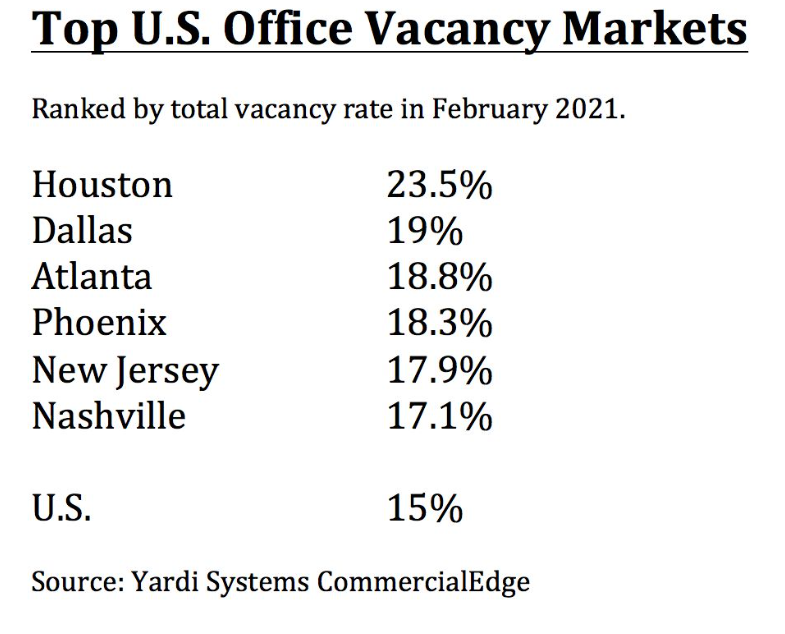

8. Top U.S. Office Vacancies.

Bloomberg Dani Romero Landlords in Houston and Dallas are having a tougher time filling their empty office buildings with new tenants than any other market in the country, according to office market statistics compiled by CoStar and JPMorgan.Why? One reason: They overbuilt when interest rates were low.

Between 2010 and 2021 the Dallas and Houston metro areas put up 48 million and 46 million square feet of new office space, according to 42 Floors, more than any other place in the country except New York City. They were No. 1 and No. 2 when counting all commercial real estate construction during that period.

Their biggest challenge is selling tenants on the older space put up during previous booms decades ago. Newer buildings that were built five years ago or less have single-digit vacancy, according to Aguirre, while older space from the 1980s is a much harder sell.

“There’s not a ton of prime space,” said Bill Kitchens, director of market analytics at CoStar Group. “We really do have to look at the configuration, the quality of the space, all those considerations that the tenants are still focused on.”

Some landlords are turning to discounts on space that can be subleased from tenants who downsized or ditched their office space for newer digs. In Houston, office subleases are being discounted by 25%-60%, according to CoStar.

“The discounts out there really haven’t moved the needle, that’s the long and short of it,” Kitchens added. “It’s going to continue to be a headache not only for our market, [but] major markets in the U.S.”

Dani Romero is a reporter for Yahoo Finance. Follow her on Twitter @daniromerotv

9. An Allergy Season So Bad You Don’t Need Allergies to Feel Miserable-WSJ

Pollen season is starting earlier and hitting harder, irritating even people who don’t usually suffer

By Alex Janin

fever, is an allergic reaction to irritants such as airborne pollens or molds that often occur in the spring. PHOTO: ALEXI ROSENFELD/GETTY IMAGES

This year’s allergy season is especially bad, making life miserable for annual sufferers as well as people who thought seasonal allergies didn’t affect them.

The pollen season this year started earlier and more forcefully than usual in some parts of the U.S., say allergists and pollen counters, meaning that even those without diagnosed allergies are wheezing, sneezing and reporting irritated and puffy eyes.

“This time of year, even people who don’t have a history of seasonal allergies can be symptomatic,” says Dr. Joyce Yu, a pediatric allergist-immunologist at Columbia University Irving Medical Center. “This winter, since it has been somewhat warm, the trees have been pollinating on the earlier side.”

True allergic rhinitis, also known as seasonal allergies or hay fever, is an allergic reaction to irritants such as airborne pollens or molds that often occur in the spring, when warmer temperatures lead trees to release pollen. About 25% of U.S. adults and 19% of children have been diagnosed with seasonal allergies, according to the National Center for Health Statistics.

Part of the reason this year is packing a bigger punch for many of us, allergists and environmental researchers say, is a warmer-than-usual winter, which meant pollen season got off to an early start. High levels of pollen can produce allergy-like symptoms, irritating the eyes and sinuses like any other environmental debris, such as campfire smoke, says Dr. Courtney Jackson Blair, an allergist-immunologist in McLean, Va.

Over-the-counter treatments such as nasal sprays and oral antihistamines might help symptoms regardless of whether they are true allergies or just irritation. Doctors recommend that people with allergy-like symptoms see a provider to rule out other health problems and develop treatment plans

10. How Will You Measure Your Life?

Don’t reserve your best business thinking for your career.

Editor’s note (2010): When the members of the class of 2010 entered business school, the economy was strong and their post-graduation ambitions could be limitless. Just a few weeks later, the economy went into a tailspin. They’ve spent the past two years recalibrating their worldview and their definition of success. The students seem highly aware of how the world has changed (as the sampling of views in this article shows). In the spring, Harvard Business School’s graduating class asked HBS professor Clay Christensen to address them—but not on how to apply his principles and thinking to their post-HBS careers. The students wanted to know how to apply them to their personal lives. He shared with them a set of guidelines that have helped him find meaning in his own life. Though Christensen’s thinking comes from his deep religious faith, we believe that these are strategies anyone can use. And so we asked him to share them with the readers of HBR.

Before I published The Innovator’s Dilemma, I got a call from Andrew Grove, then the chairman of Intel. He had read one of my early papers about disruptive technology, and he asked if I could talk to his direct reports and explain my research and what it implied for Intel. Excited, I flew to Silicon Valley and showed up at the appointed time, only to have Grove say, “Look, stuff has happened. We have only 10 minutes for you. Tell us what your model of disruption means for Intel.” I said that I couldn’t—that I needed a full 30 minutes to explain the model, because only with it as context would any comments about Intel make sense. Ten minutes into my explanation, Grove interrupted: “Look, I’ve got your model. Just tell us what it means for Intel.”

I insisted that I needed 10 more minutes to describe how the process of disruption had worked its way through a very different industry, steel, so that he and his team could understand how disruption worked. I told the story of how Nucor and other steel minimills had begun by attacking the lowest end of the market—steel reinforcing bars, or rebar—and later moved up toward the high end, undercutting the traditional steel mills.

When I finished the minimill story, Grove said, “OK, I get it. What it means for Intel is…,” and then went on to articulate what would become the company’s strategy for going to the bottom of the market to launch the Celeron processor.

I’ve thought about that a million times since. If I had been suckered into telling Andy Grove what he should think about the microprocessor business, I’d have been killed. But instead of telling him what to think, I taught him how to think—and then he reached what I felt was the correct decision on his own.

That experience had a profound influence on me. When people ask what I think they should do, I rarely answer their question directly. Instead, I run the question aloud through one of my models. I’ll describe how the process in the model worked its way through an industry quite different from their own. And then, more often than not, they’ll say, “OK, I get it.” And they’ll answer their own question more insightfully than I could have.

My class at HBS is structured to help my students understand what good management theory is and how it is built. To that backbone I attach different models or theories that help students think about the various dimensions of a general manager’s job in stimulating innovation and growth. In each session we look at one company through the lenses of those theories—using them to explain how the company got into its situation and to examine what managerial actions will yield the needed results.

On the last day of class, I ask my students to turn those theoretical lenses on themselves, to find cogent answers to three questions: First, how can I be sure that I’ll be happy in my career? Second, how can I be sure that my relationships with my spouse and my family become an enduring source of happiness? Third, how can I be sure I’ll stay out of jail? Though the last question sounds lighthearted, it’s not. Two of the 32 people in my Rhodes scholar class spent time in jail. Jeff Skilling of Enron fame was a classmate of mine at HBS. These were good guys—but something in their lives sent them off in the wrong direction.

Doing deals doesn’t yield the deep rewards that come from building up people.

As the students discuss the answers to these questions, I open my own life to them as a case study of sorts, to illustrate how they can use the theories from our course to guide their life decisions.

One of the theories that gives great insight on the first question—how to be sure we find happiness in our careers—is from Frederick Herzberg, who asserts that the powerful motivator in our lives isn’t money; it’s the opportunity to learn, grow in responsibilities, contribute to others, and be recognized for achievements. I tell the students about a vision of sorts I had while I was running the company I founded before becoming an academic. In my mind’s eye I saw one of my managers leave for work one morning with a relatively strong level of self-esteem. Then I pictured her driving home to her family 10 hours later, feeling unappreciated, frustrated, underutilized, and demeaned. I imagined how profoundly her lowered self-esteem affected the way she interacted with her children. The vision in my mind then fast-forwarded to another day, when she drove home with greater self-esteem—feeling that she had learned a lot, been recognized for achieving valuable things, and played a significant role in the success of some important initiatives. I then imagined how positively that affected her as a spouse and a parent. My conclusion: Management is the most noble of professions if it’s practiced well. No other occupation offers as many ways to help others learn and grow, take responsibility and be recognized for achievement, and contribute to the success of a team. More and more MBA students come to school thinking that a career in business means buying, selling, and investing in companies. That’s unfortunate. Doing deals doesn’t yield the deep rewards that come from building up people.

I want students to leave my classroom knowing that.

Create a Strategy for Your Life

A theory that is helpful in answering the second question—How can I ensure that my relationship with my family proves to be an enduring source of happiness?—concerns how strategy is defined and implemented. Its primary insight is that a company’s strategy is determined by the types of initiatives that management invests in. If a company’s resource allocation process is not managed masterfully, what emerges from it can be very different from what management intended. Because companies’ decision-making systems are designed to steer investments to initiatives that offer the most tangible and immediate returns, companies shortchange investments in initiatives that are crucial to their long-term strategies.

Over the years I’ve watched the fates of my HBS classmates from 1979 unfold; I’ve seen more and more of them come to reunions unhappy, divorced, and alienated from their children. I can guarantee you that not a single one of them graduated with the deliberate strategy of getting divorced and raising children who would become estranged from them. And yet a shocking number of them implemented that strategy. The reason? They didn’t keep the purpose of their lives front and center as they decided how to spend their time, talents, and energy.

It’s quite startling that a significant fraction of the 900 students that HBS draws each year from the world’s best have given little thought to the purpose of their lives. I tell the students that HBS might be one of their last chances to reflect deeply on that question. If they think that they’ll have more time and energy to reflect later, they’re nuts, because life only gets more demanding: You take on a mortgage; you’re working 70 hours a week; you have a spouse and children.

For me, having a clear purpose in my life has been essential. But it was something I had to think long and hard about before I understood it. When I was a Rhodes scholar, I was in a very demanding academic program, trying to cram an extra year’s worth of work into my time at Oxford. I decided to spend an hour every night reading, thinking, and praying about why God put me on this earth. That was a very challenging commitment to keep, because every hour I spent doing that, I wasn’t studying applied econometrics. I was conflicted about whether I could really afford to take that time away from my studies, but I stuck with it—and ultimately figured out the purpose of my life.

Had I instead spent that hour each day learning the latest techniques for mastering the problems of autocorrelation in regression analysis, I would have badly misspent my life. I apply the tools of econometrics a few times a year, but I apply my knowledge of the purpose of my life every day. It’s the single most useful thing I’ve ever learned. I promise my students that if they take the time to figure out their life purpose, they’ll look back on it as the most important thing they discovered at HBS. If they don’t figure it out, they will just sail off without a rudder and get buffeted in the very rough seas of life. Clarity about their purpose will trump knowledge of activity-based costing, balanced scorecards, core competence, disruptive innovation, the four Ps, and the five forces.

My purpose grew out of my religious faith, but faith isn’t the only thing that gives people direction. For example, one of my former students decided that his purpose was to bring honesty and economic prosperity to his country and to raise children who were as capably committed to this cause, and to each other, as he was. His purpose is focused on family and others—as mine is.

The choice and successful pursuit of a profession is but one tool for achieving your purpose. But without a purpose, life can become hollow.

Allocate Your Resources

Your decisions about allocating your personal time, energy, and talent ultimately shape your life’s strategy.

I have a bunch of “businesses” that compete for these resources: I’m trying to have a rewarding relationship with my wife, raise great kids, contribute to my community, succeed in my career, contribute to my church, and so on. And I have exactly the same problem that a corporation does. I have a limited amount of time and energy and talent. How much do I devote to each of these pursuits?

Allocation choices can make your life turn out to be very different from what you intended. Sometimes that’s good: Opportunities that you never planned for emerge. But if you misinvest your resources, the outcome can be bad. As I think about my former classmates who inadvertently invested for lives of hollow unhappiness, I can’t help believing that their troubles relate right back to a short-term perspective.

When people who have a high need for achievement—and that includes all Harvard Business School graduates—have an extra half hour of time or an extra ounce of energy, they’ll unconsciously allocate it to activities that yield the most tangible accomplishments. And our careers provide the most concrete evidence that we’re moving forward. You ship a product, finish a design, complete a presentation, close a sale, teach a class, publish a paper, get paid, get promoted. In contrast, investing time and energy in your relationship with your spouse and children typically doesn’t offer that same immediate sense of achievement. Kids misbehave every day. It’s really not until 20 years down the road that you can put your hands on your hips and say, “I raised a good son or a good daughter.” You can neglect your relationship with your spouse, and on a day-to-day basis, it doesn’t seem as if things are deteriorating. People who are driven to excel have this unconscious propensity to underinvest in their families and overinvest in their careers—even though intimate and loving relationships with their families are the most powerful and enduring source of happiness.

If you study the root causes of business disasters, over and over you’ll find this predisposition toward endeavors that offer immediate gratification. If you look at personal lives through that lens, you’ll see the same stunning and sobering pattern: people allocating fewer and fewer resources to the things they would have once said mattered most.

Create a Culture

There’s an important model in our class called the Tools of Cooperation, which basically says that being a visionary manager isn’t all it’s cracked up to be. It’s one thing to see into the foggy future with acuity and chart the course corrections that the company must make. But it’s quite another to persuade employees who might not see the changes ahead to line up and work cooperatively to take the company in that new direction. Knowing what tools to wield to elicit the needed cooperation is a critical managerial skill.

The theory arrays these tools along two dimensions—the extent to which members of the organization agree on what they want from their participation in the enterprise, and the extent to which they agree on what actions will produce the desired results. When there is little agreement on both axes, you have to use “power tools”—coercion, threats, punishment, and so on—to secure cooperation. Many companies start in this quadrant, which is why the founding executive team must play such an assertive role in defining what must be done and how. If employees’ ways of working together to address those tasks succeed over and over, consensus begins to form. MIT’s Edgar Schein has described this process as the mechanism by which a culture is built. Ultimately, people don’t even think about whether their way of doing things yields success. They embrace priorities and follow procedures by instinct and assumption rather than by explicit decision—which means that they’ve created a culture. Culture, in compelling but unspoken ways, dictates the proven, acceptable methods by which members of the group address recurrent problems. And culture defines the priority given to different types of problems. It can be a powerful management tool.

In using this model to address the question, How can I be sure that my family becomes an enduring source of happiness?, my students quickly see that the simplest tools that parents can wield to elicit cooperation from children are power tools. But there comes a point during the teen years when power tools no longer work. At that point parents start wishing that they had begun working with their children at a very young age to build a culture at home in which children instinctively behave respectfully toward one another, obey their parents, and choose the right thing to do. Families have cultures, just as companies do. Those cultures can be built consciously or evolve inadvertently.

If you want your kids to have strong self-esteem and confidence that they can solve hard problems, those qualities won’t magically materialize in high school. You have to design them into your family’s culture—and you have to think about this very early on. Like employees, children build self-esteem by doing things that are hard and learning what works.

Avoid the “Marginal Costs” Mistake

We’re taught in finance and economics that in evaluating alternative investments, we should ignore sunk and fixed costs, and instead base decisions on the marginal costs and marginal revenues that each alternative entails. We learn in our course that this doctrine biases companies to leverage what they have put in place to succeed in the past, instead of guiding them to create the capabilities they’ll need in the future. If we knew the future would be exactly the same as the past, that approach would be fine. But if the future’s different—and it almost always is—then it’s the wrong thing to do.

This theory addresses the third question I discuss with my students—how to live a life of integrity (stay out of jail). Unconsciously, we often employ the marginal cost doctrine in our personal lives when we choose between right and wrong. A voice in our head says, “Look, I know that as a general rule, most people shouldn’t do this. But in this particular extenuating circumstance, just this once, it’s OK.” The marginal cost of doing something wrong “just this once” always seems alluringly low. It suckers you in, and you don’t ever look at where that path ultimately is headed and at the full costs that the choice entails. Justification for infidelity and dishonesty in all their manifestations lies in the marginal cost economics of “just this once.”

I’d like to share a story about how I came to understand the potential damage of “just this once” in my own life. I played on the Oxford University varsity basketball team. We worked our tails off and finished the season undefeated. The guys on the team were the best friends I’ve ever had in my life. We got to the British equivalent of the NCAA tournament—and made it to the final four. It turned out the championship game was scheduled to be played on a Sunday. I had made a personal commitment to God at age 16 that I would never play ball on Sunday. So I went to the coach and explained my problem. He was incredulous. My teammates were, too, because I was the starting center. Every one of the guys on the team came to me and said, “You’ve got to play. Can’t you break the rule just this one time?”

I’m a deeply religious man, so I went away and prayed about what I should do. I got a very clear feeling that I shouldn’t break my commitment—so I didn’t play in the championship game.

In many ways that was a small decision—involving one of several thousand Sundays in my life. In theory, surely I could have crossed over the line just that one time and then not done it again. But looking back on it, resisting the temptation whose logic was “In this extenuating circumstance, just this once, it’s OK” has proven to be one of the most important decisions of my life. Why? My life has been one unending stream of extenuating circumstances. Had I crossed the line that one time, I would have done it over and over in the years that followed.

The lesson I learned from this is that it’s easier to hold to your principles 100% of the time than it is to hold to them 98% of the time. If you give in to “just this once,” based on a marginal cost analysis, as some of my former classmates have done, you’ll regret where you end up. You’ve got to define for yourself what you stand for and draw the line in a safe place.

Remember the Importance of Humility

I got this insight when I was asked to teach a class on humility at Harvard College. I asked all the students to describe the most humble person they knew. One characteristic of these humble people stood out: They had a high level of self-esteem. They knew who they were, and they felt good about who they were. We also decided that humility was defined not by self-deprecating behavior or attitudes but by the esteem with which you regard others. Good behavior flows naturally from that kind of humility. For example, you would never steal from someone, because you respect that person too much. You’d never lie to someone, either.

It’s crucial to take a sense of humility into the world. By the time you make it to a top graduate school, almost all your learning has come from people who are smarter and more experienced than you: parents, teachers, bosses. But once you’ve finished at Harvard Business School or any other top academic institution, the vast majority of people you’ll interact with on a day-to-day basis may not be smarter than you. And if your attitude is that only smarter people have something to teach you, your learning opportunities will be very limited. But if you have a humble eagerness to learn something from everybody, your learning opportunities will be unlimited. Generally, you can be humble only if you feel really good about yourself—and you want to help those around you feel really good about themselves, too. When we see people acting in an abusive, arrogant, or demeaning manner toward others, their behavior almost always is a symptom of their lack of self-esteem. They need to put someone else down to feel good about themselves.

Choose the Right Yardstick

This past year I was diagnosed with cancer and faced the possibility that my life would end sooner than I’d planned. Thankfully, it now looks as if I’ll be spared. But the experience has given me important insight into my life.

I have a pretty clear idea of how my ideas have generated enormous revenue for companies that have used my research; I know I’ve had a substantial impact. But as I’ve confronted this disease, it’s been interesting to see how unimportant that impact is to me now. I’ve concluded that the metric by which God will assess my life isn’t dollars but the individual people whose lives I’ve touched.

I think that’s the way it will work for us all. Don’t worry about the level of individual prominence you have achieved; worry about the individuals you have helped become better people. This is my final recommendation: Think about the metric by which your life will be judged, and make a resolution to live every day so that in the end, your life will be judged a success.

A version of this article appeared in the July–August 2010 issue of Harvard Business Review.

Read more on Personal ethics or related topics Personal strategy and style, Personal purpose and values and Managing yourself

- Clayton M. Christensen was the Kim B. Clark Professor of Business Administration at Harvard Business School and a frequent contributor to Harvard Business Review.