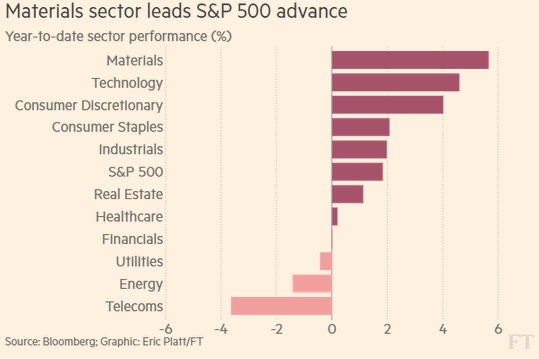

1.Materials Take Over Sector Leadership.

XLB Breaks out of 4 Year Range.

www.stockcharts.com

www.stockcharts.com

Top Holdings.

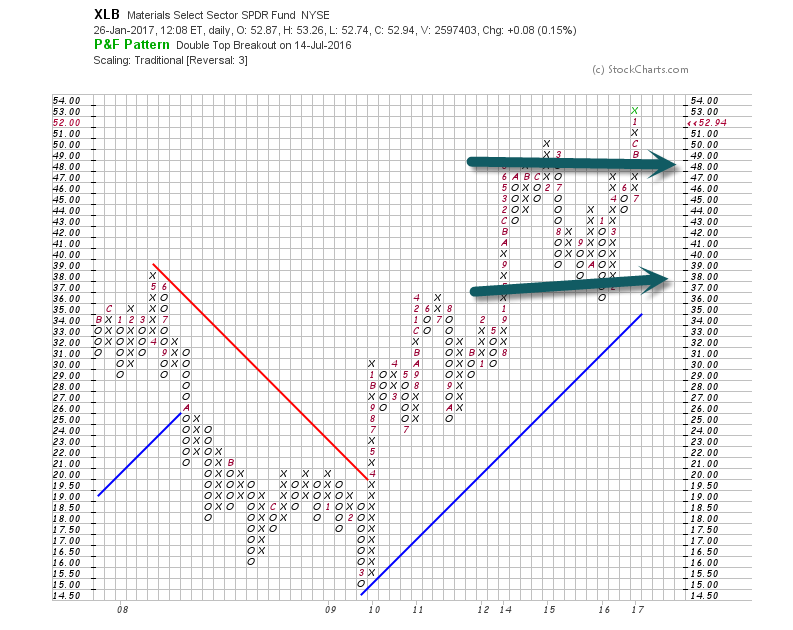

2.What the U.S. and Mexico Trade.

Both the U.S. and Mexico have benefited from the controversial trade agreement that went into effect under President Bill Clinton in 1994, but Mexico has arguably been the bigger winner.

After running a trade deficit with the U.S. from 1991 to 1994, Mexico moved to a surplus in 1995, and that’s been the case ever since. Mexico has become a major producer of automobiles, electronics and appliances, to go along with its status as a large oil exporter.

As a result, U.S. imports from Mexico soared from $65 billion when the North American trade deal was passed to around $295 billion in 2016.

The U.S. has been helped, too, especially in border states such as Texas. Exports to Mexico have climbed from $68 billion in 1994 to an estimated $235 billion in 2016.

As Trump pointed out, though, the U.S. is on track to run a trade deficit of close to $60 billion with Mexico in 2016, according to government data. That’s about 12% of the nation’s overall annual trade gap.

http://www.marketwatch.com/story/trump-calls-us-mexico-trade-one-sided-heres-the-reality-2017-01-26

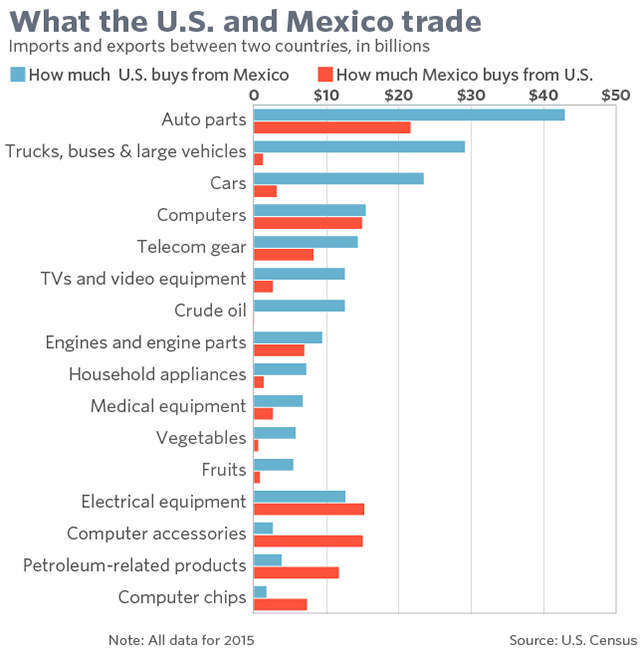

3.Short-Term Consensus Bulls on S&P 500 are in the 90th Percentile.

Jeff DeGraff

www.renmac.com

Reach out to EBoucher@renmac.com

4.The Great 2008 Hangover….Sell Side Never Got Overly Bullish.

http://www.businessinsider.com/sell-side-indicator-september-2015-2015-10

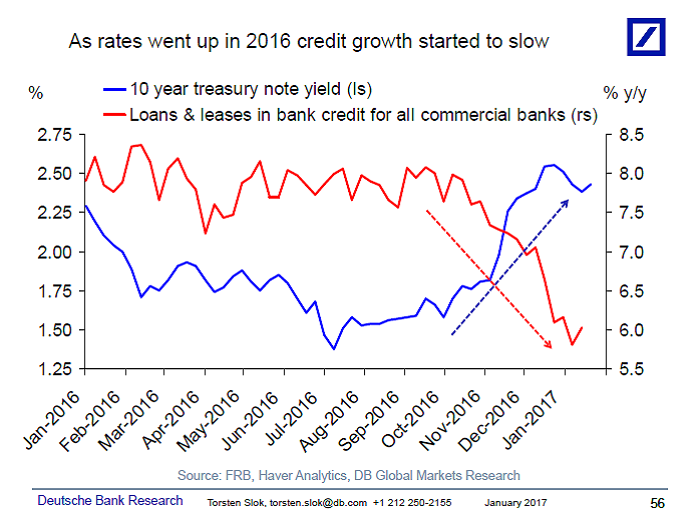

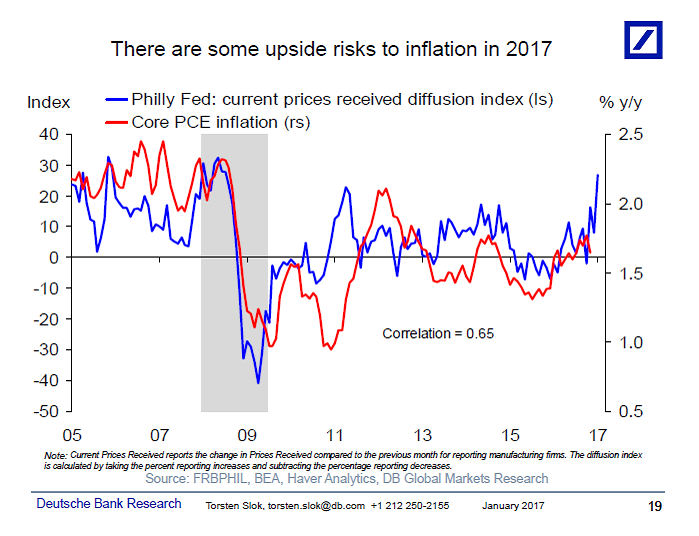

5.Torsten Slok with Charts on Rates and Credit Growth.

We are watching very carefully the impact of higher rates on the economy, and there are some signs that the move up in rates in recent months is having a negative impact on the economy, see the first chart below. The slowdown in credit growth is not dramatic, see the second chart, but the sensitivity of the economy to higher rates continues to be a topic that comes up in my client conversations at the moment, and many clients I talk to believe that the economy and the stock market will not be able to handle a Fed funds rate at 2% or 3% and 10-year rates at 3% or 4%. The biggest organic risk to the view that “rates will be low forever” is an upside surprise in inflation, see also the third chart and my latest monthly chart book.

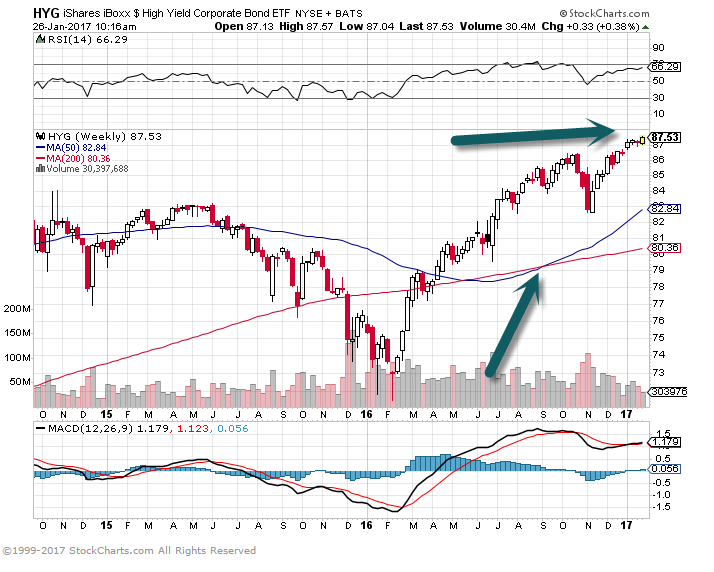

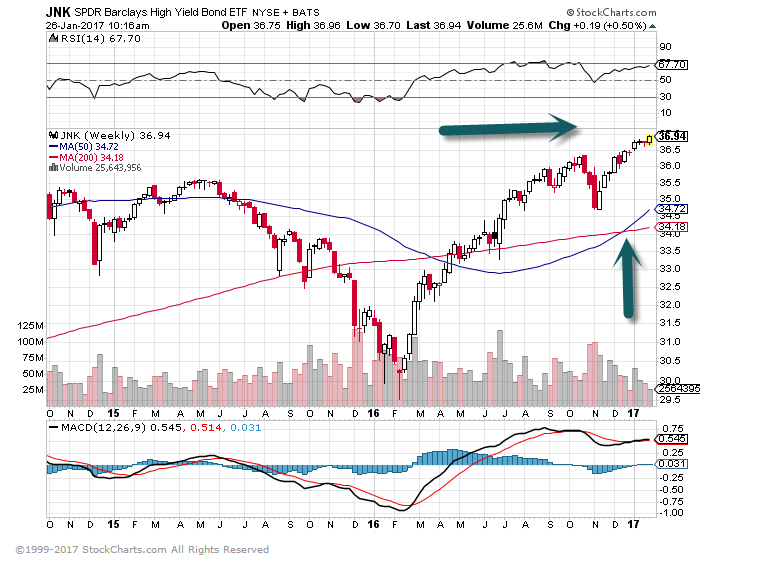

6.Triple C Paper Trading at Yields as Low as 6%…Last Feb. Yield was 18.57%.

GOT JUNK?– Investors’ appetite for the lowest rated segments of the corporate debt market touched a fresh peak on Wednesday, when a triple-C rated company came close to selling bonds with a yield of just 6 per cent. Last February, triple-C paper traded with a yield of 18.57 per cent, according to Bloomberg Barclays Indices. That figure has nearly halved to 9.36 per cent today. “Triple-Cs are routinely pricing at 7 per cent or less. The compensation you get paid to take risk is getting narrower and narrower, much like in 1997-98 and 2004-2006.”

Stats from Dave Lutz at Jones.

High Yield ETFs

HYG-50day thru 200day to upside and new highs.

JNK-50day thru 200day to upside and new highs.

7.Demographics is Destiny.

7.Demographics is Destiny.

From Mike Nolan at Janney Letter.

One of the biggest drivers of equity bull markets are demographics. Despite all the mixed emotions society has towards the millennial generation it is more likely than not that this group will do the same thing that all those generations before them have… buy homes, buy cars, form families, save for retirement, etc. This means more people consuming more things. Those peak spending years come during their “nesting” phase. They may be doing these things later in life, but they are also living longer.

mnolan@janney.com

mnolan@janney.com

www.michaelnolan-janney.com

8.Chapter 11 Bankruptcies.

www.thedailyshot.com

www.thedailyshot.com

9.Read of the Day…. In the past five years the profits of multinationals have dropped by 25%

The multinational company is in trouble

Global firms are surprisingly vulnerable to attack

AMONG the many things that Donald Trump dislikes are big global firms. Faceless and rootless, they stand accused of unleashing “carnage” on ordinary Americans by shipping jobs and factories abroad. His answer is to domesticate these marauding multinationals. Lower taxes will draw their cash home, border charges will hobble their cross-border supply chains and the trade deals that help them do business will be rewritten. To avoid punitive treatment, “all you have to do is stay,” he told American bosses this week.

Mr. Trump is unusual in his aggressively protectionist tone. But in many ways he is behind the times. Multinational companies, the agents behind global integration, were already in retreat well before the populist revolts of 2016. Their financial performance has slipped so that they are no longer outstripping local firms. Many seem to have exhausted their ability to cut costs and taxes and to out-think their local competitors. Mr Trump’s broadsides are aimed at companies that are surprisingly vulnerable and, in many cases, are already heading home. The impact on global commerce will be profound.

Multinational firms (those that do a large chunk of their business outside their home region) employ only one in 50 of the world’s workers. But they matter. A few thousand firms influence what billions of people watch, wear and eat. The likes of IBM, McDonald’s, Ford, H&M, Infosys, Lenovo and Honda have been the benchmark for managers. They co-ordinate the supply chains that account for over 50% of all trade. They account for a third of the value of the world’s stockmarkets and they own the lion’s share of its intellectual property—from lingerie designs to virtual-reality software and diabetes drugs.

They boomed in the early 1990s, as China and the former Soviet bloc opened and Europe integrated. Investors liked global firms’ economies of scale and efficiency. Rather than running themselves as national fiefs, firms unbundled their functions. A Chinese factory might use tools from Germany, have owners in the United States, pay taxes in Luxembourg and sell to Japan. Governments in the rich world dreamed of their national champions becoming world-beaters. Governments in the emerging world welcomed the jobs, exports and technology that global firms brought. It was a golden age.

Central to the rise of the global firm was its claim to be a superior moneymaking machine. That claim lies in tatters (see Briefing). In the past five years the profits of multinationals have dropped by 25%. Returns on capital have slipped to their lowest in two decades. A strong dollar and a low oil price explain part of the decline. Technology superstars and consumer firms with strong brands are still thriving. But the pain is too widespread and prolonged to be dismissed as a blip. About 40% of all multinationals make a return on equity of less than 10%, a yardstick for underperformance. In a majority of industries they are growing more slowly and are less profitable than local firms that stayed in their backyard. The share of global profits accounted for by multinationals has fallen from 35% a decade ago to 30% now. For many industrial, manufacturing, financial, natural-resources, media and telecoms companies, global reach has become a burden, not an advantage.

That is because a 30-year window of arbitrage is closing. Firms’ tax bills have been massaged down as low as they can go; in China factory workers’ wages are rising. Local firms have become more sophisticated. They can steal, copy or displace global firms’ innovations without building costly offices and factories abroad. From America’s shale industry to Brazilian banking, from Chinese e-commerce to Indian telecoms, the companies at the cutting edge are local, not global.

The changing political landscape is making things even harder for the giants. Mr Trump is the latest and most strident manifestation of a worldwide shift to grab more of the value that multinationals capture. China wants global firms to place not just their supply chains there, but also their brainiest activities such as research and development. Last year Europe and America battled over who gets the $13bn of tax that Apple and Pfizer pay annually. From Germany to Indonesia rules on takeovers, antitrust and data are tightening.

Mr Trump’s arrival will only accelerate a gory process of restructuring. Many firms are simply too big: they will have to shrink their empires. Others are putting down deeper roots in the markets where they operate. General Electric and Siemens are “localising” supply chains, production, jobs and tax into regional or national units. Another strategy is to become “intangible”. Silicon Valley’s stars, from Uber to Google, are still expanding abroad. Fast-food firms and hotel chains are shifting from flipping burgers and making beds to selling branding rights. But such virtual multinationals are also vulnerable to populism because they create few direct jobs, pay little tax and are not protected by trade rules designed for physical goods.

Taking back control

The retreat of global firms will give politicians a feeling of greater control as companies promise to do their bidding. But not every country can get a bigger share of the same firms’ production, jobs and tax. And a rapid unwinding of the dominant form of business of the past 20 years could be chaotic. Many countries with trade deficits (including “global Britain”) rely on the flow of capital that multinationals bring. If firms’ profits drop further, the value of stockmarkets will probably fall.

What of consumers and voters? They touch screens, wear clothes and are kept healthy by the products of firms that they dislike as immoral, exploitative and aloof. The golden age of global firms has also been a golden age for consumer choice and efficiency. Its demise may make the world seem fairer. But the retreat of the multinational cannot bring back all the jobs that the likes of Mr Trump promise. And it will mean rising prices, diminishing competition and slowing innovation. In time, millions of small firms trading across borders could replace big firms as transmitters of ideas and capital. But their weight is tiny. People may yet look back on the era when global firms ruled the business world, and regret its passing.

http://www.economist.com/news/leaders/21715660-global-firms-are-surprisingly-vulnerable-attack-multinational-company-trouble

Found on Abnormal Returns Blog

www.abnormalreturns.com

10.It Took a Successful NBA Coach Only 2 Sentences to Drop the Best Advice You’ll Hear Today

Quit looking at others and focus on this.

By Justin Bariso

The Boston Celtics introduced new head coach Brad Stevens at their Waltham practice facility, July 5, 2013.

CREDIT: Getty Images

In 2013, the Boston Celtics took a chance when they hired unproven 36-year-old Brad Stevens as the team’s head coach. Since then, Stevens has helped turn the storied franchise around, taking the Celtics from the bottom of the pack to the third best team in the Eastern Conference (at time of writing).

So, how does Stevens stay focused, in a league that has been dominated by just a few superpowers in recent years? In a recent interview, Stevens summed up his philosophy in two short sentences:

“I’m not even thinking about any other team. We’re trying to be the best version of ourselves.”

Stevens’s doctrine should hit home for most of us. It’s much too easy to compare ourselves to colleagues, friends, and family members — in respect to everything from our current job title to the type of car we drive.

But there are many reasons you should resist comparing yourself to others.

Here are three of them:

It feeds “the envy animal.”

It’s easy to stay positive when you cultivate an attitude of appreciation. In contrast, putting too much emphasis on others is dangerous — because there will always be someone who’s more skilled or who has more than you, at least in certain areas.

When you instead focus on your own strengths and resources, you can maximize these and be motivated to give your best effort.

The process matters.

Learning from others can be useful…to an extent. But it takes time for good ideas and hard work to reap rewards. Any success you see from friends or competitors was no doubt preceded by repeated failures and a long struggle — much of which you’re either forgetting about or unaware of.

Don’t rob yourself of your own payoff by comparing yourself to others. Instead, keep your head down, work hard, and stay consistent. Good things will come in time.

You need to define success.

Remember: You need to define what success means to you.

I once had a friend whose career took off quickly. She was happy with her company, her position, and her overall quality of life — until she started comparing herself with friends who seemed to be climbing the ladder a little faster than she was. Those constant comparisons made her really question her worth.

But a mentor advised her to refocus on the positives in her life and quit comparing herself with others. She quickly regained her joy and has thrived ever since.

While you may believe that others are doing better than you, you might not feel the same if you knew their whole situation. And in reality, their achievements have nothing to do with your happiness.

So, take time to define what’s important to you. Is it doing what you love? Providing value to others? Having enough time for friends and family?

By figuring out what really matters, and then sticking to those priorities, you become the best version of yourself.

And that’s what I call success.

http://www.inc.com/justin-bariso/it-took-a-successful-nba-coach-only-2-sentences-to-drop-the-best-advice-youll-he.html