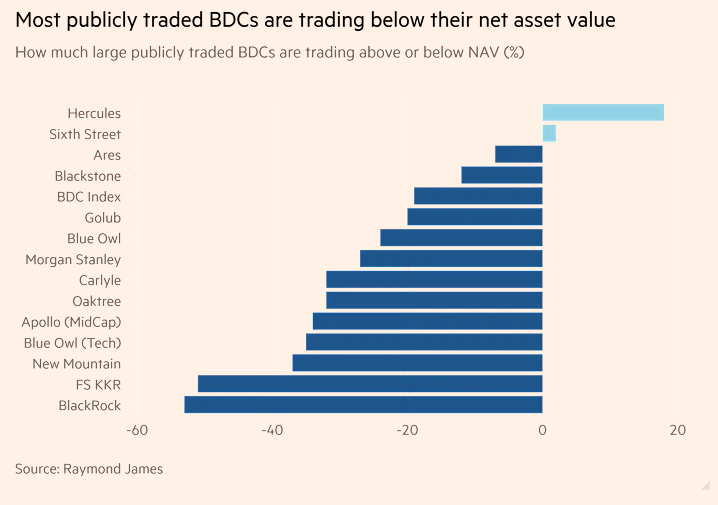

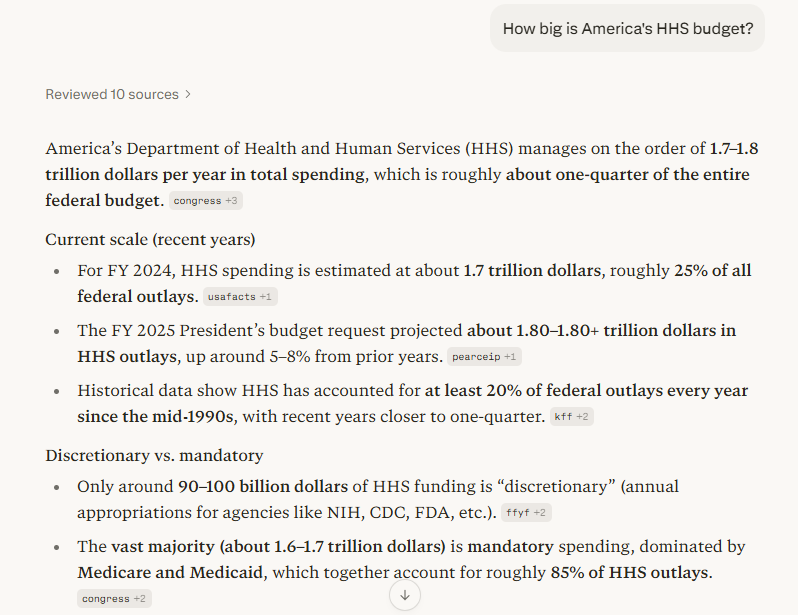

1. Redemption Requests for Non-Traded BDC’s

Bloomberg

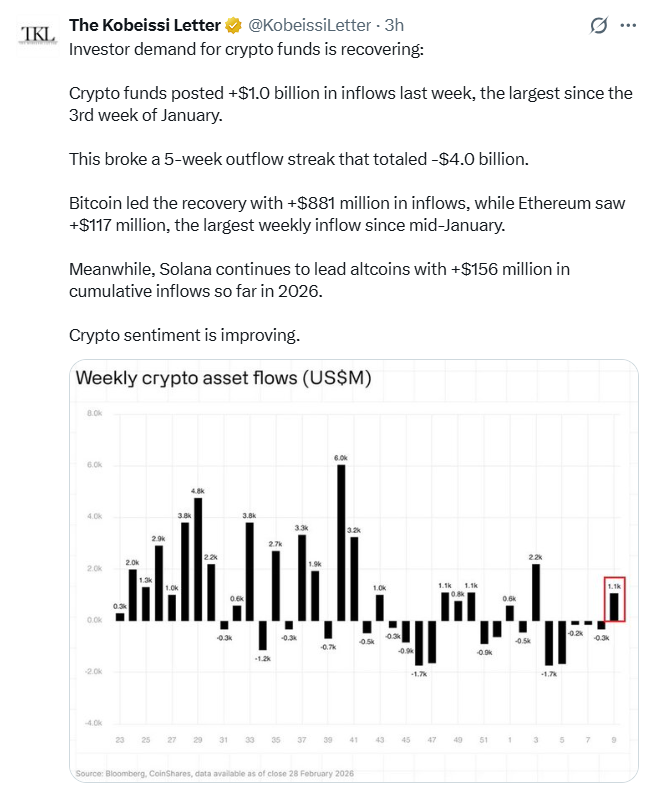

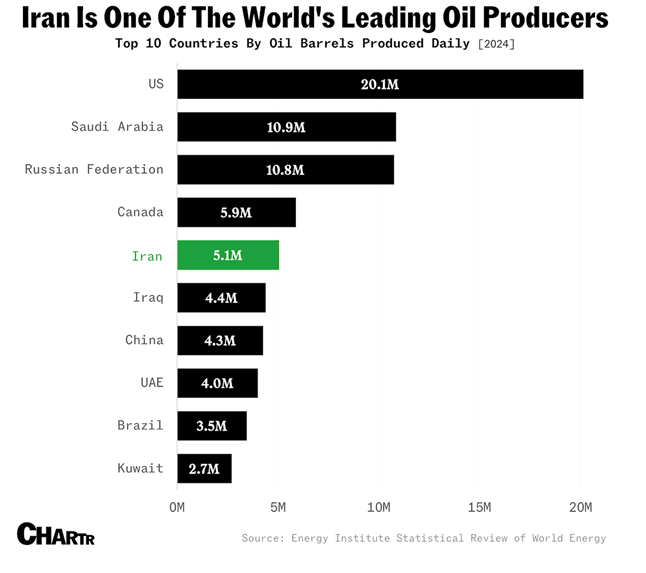

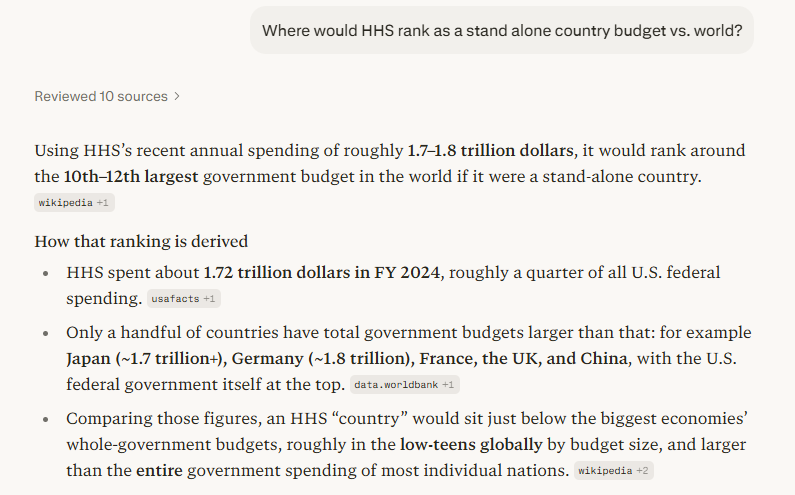

2. South Korea Leverage Stocks Bets Hit Record

Dave Lutz Jones Trading Retail traders in Asia are loading up on borrowed money to fund purchases in their brokerage accounts, traders and dealers said, as they chase oil and energy prices higher and scoop up sinking stocks. Investors have made fresh margin payments to extend positions as well as top up where they have incurred losses, brokers said. The behavior is emblematic of a habit of dip buying honed in seemingly unstoppable markets in the years since retail trading exploded in popularity during pandemic lockdowns – one which has repeatedly proven highly lucrative.

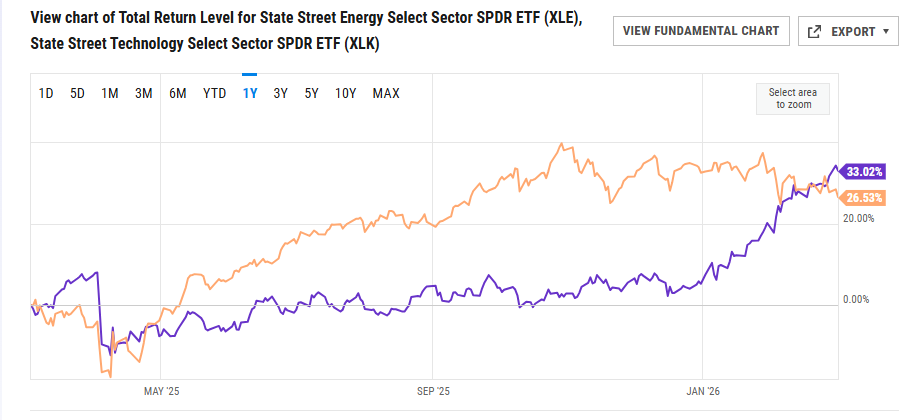

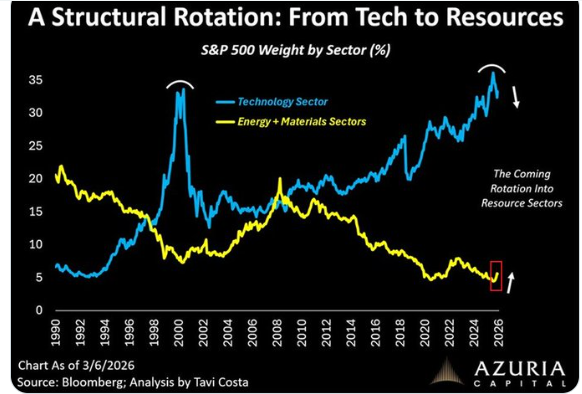

3. 2012-2024 Tech vs. Energy/Materials

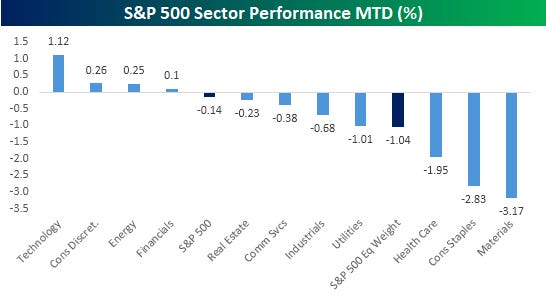

The Kobeissi Letter

4. Banks -10% Correction

Barchart

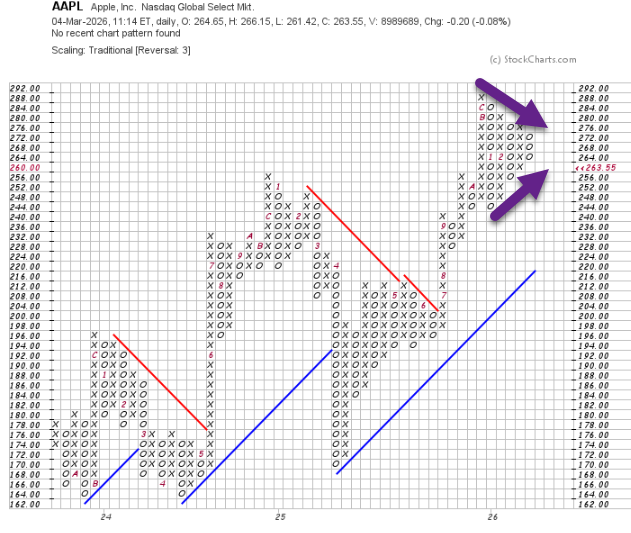

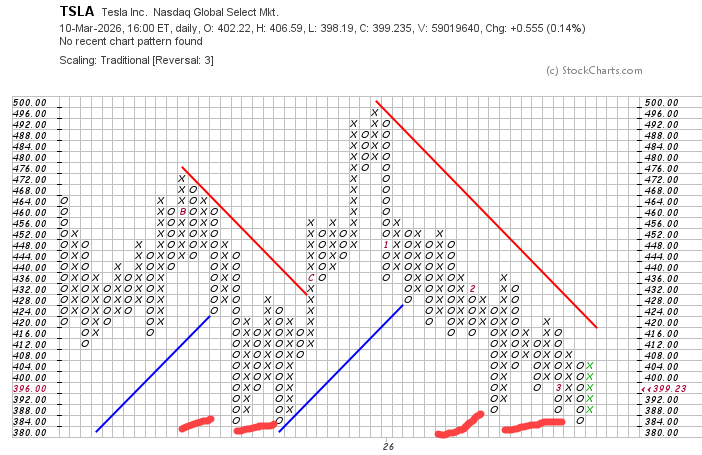

5. TSLA Holds Level for 4th Time in One-Year

StockCharts

6. HIMS Pulled Back to 2024 Levels Before this Week’s Rally…40% of Float Short

StockCharts

7. Tether And The Hidden Demand For U.S. Treasuries-The Crypto Advisor Blog

One of the more remarkable data points in digital assets today is this: if Tether were a country, it would rank among the top-20 foreign holders of U.S. government debt. According to the company’s most recent attestation, Tether holds roughly $122 billion in direct U.S. Treasury bills backing its USDT stablecoin. At that level, it would sit around 17th place globally, ahead of countries such as Israel and Germany and just behind major sovereign holders like Saudi Arabia and Brazil. For context, the threshold to enter the top 10 foreign holders of Treasuries is roughly $310 billion, meaning Tether would need to add about $190 billion more – more than double its current holdings – to reach that tier.

What makes this especially notable is how quickly those reserves have grown. Tether’s Treasury exposure has expanded dramatically alongside the growth of stablecoins and digital-dollar liquidity inside crypto markets.

- Q4 2021: ~$34.5B in U.S. Treasury bills

- Q4 2022: ~$39.2B

- Q4 2023: ~$63.1B

- Q4 2024: ~$94.5B

- Most recent: ~$122B

Over roughly four years, Tether’s direct Treasury holdings have increased by more than $85 billion, including about $27–28 billion added in just the past year. This rise closely tracks the expansion of USDT itself. Tether’s market capitalization has grown from roughly $68 billion at the end of 2021 to more than $180 billion today, reinforcing the direct relationship between stablecoin issuance and demand for short-term U.S. government debt.

https://thecryptoadvisor.substack.com

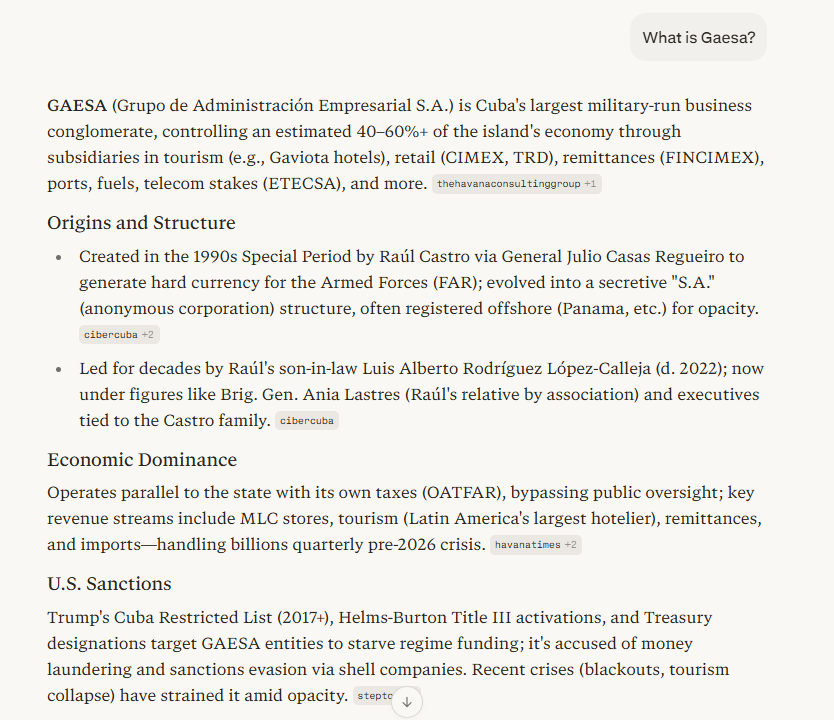

8. What is Gaesa? Cuba’s Military Business Conglomerate

Perplexity

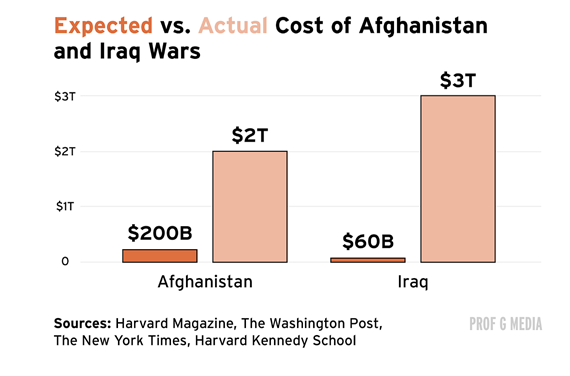

9. Expected vs. Actual Costs Afghanistan and Iraq-Prof G Blog Ed Elson

Ed Elson’s

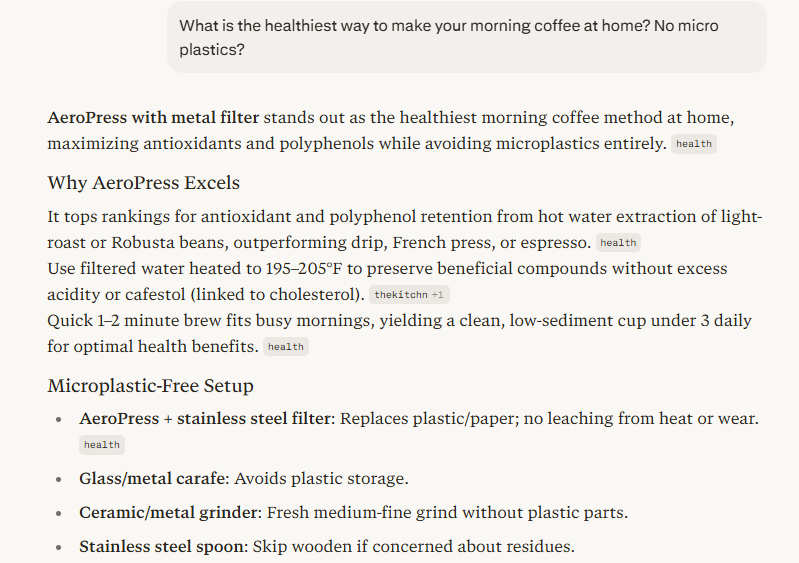

10. Healthiest Way to Make Coffee at Home-Perplexity

Perplexity