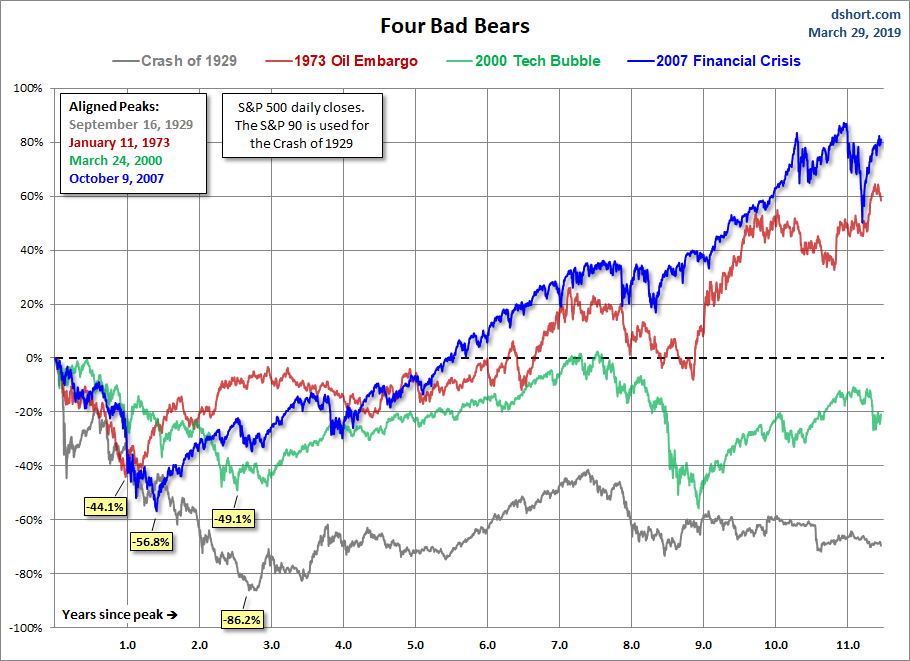

1.Recovery Comparison of 4 Major U.S. Bear Market Recoveries.

The Four Totally Bad Bear Recoveries: Where Is Today’s Market?

by Jill Mislinski, 4/4/19

In response to a standing request, here is an updated comparison of four major secular bear markets. The numbers are through the Friday, March 29 close.

This chart series features an overlay of the Four Bad Bears in U.S. history since the equity market peak in 1929. They are:

- The Crash of 1929, which eventually ushered in the Great Depression,

- The Oil Embargo of 1973, which was followed by a vicious bout of stagflation,

- The Tech Bubblecrash and,

- The Financial Crisisfollowing the record high in October 2007.

The series includes four versions of the overlay: nominal, real (inflation-adjusted), total return with dividends reinvested and real total return. The starting point is the aligned peaks prior to the four epic declines. We’ve used an interval of 252 days for the x-axis as it is roughly the number of market days in a calendar year.

The first chart shows the price, excluding dividends for these four historic declines and their aftermath. As of the year-end close, we are now 2,887 market days from the 2007 peak in the S&P 500.

2. New chart shows market rebound off December low is reminiscent of the 1998 tech boom

Stephanie Landsman | @stephlandsman

The market rally is mimicking a trend that hasn’t been seen in more than two decades, according to Avalon Advisors’ Bill Stone.

He highlighted the pattern on CNBC’s “Trading Nation” in a chart that compares 2018-2019 sharp gains with the average rebound during post-World War II non-recessionary periods.

Stone’s takeaway: It looks a lot like the dot-com boom based on 65 trading days since the December low.

“This rally is second only to that 1998 rally in terms of the strength of it,” the firm’s chief investment officer said Wednesday.

Bill Stone Avalon Advisors Interview

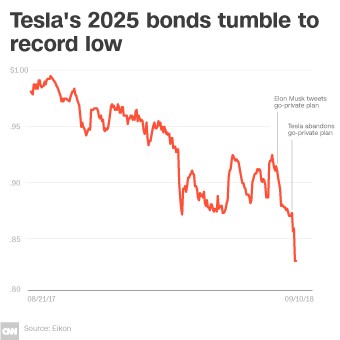

3.Tesla’s junk bonds sink to their lowest level yet below 85 cents on the dollar

Tesla Inc.’s TSLA, +0.45% high-yield bonds fell to a fresh record low on Friday, as investors digested the news that the company’s chief accounting officer has quit. The 5.300% notes that mature in August of 2025 fell to 84.999 cents on the dollar, according to trading platform MarketAxess, to yield 8.178%. On a spread basis, the bonds were trading at 527 basis points over Treasurys, 36 basis points wider on the day. The bonds have fallen along with the stock amid concerns about the erratic behavior of Chief Executive Elon Musk. In the latest move stirring controversy, Musk appeared to smoke marijuana during an interview on “The Joe Rogan Experience” podcast late Thursday. Shares were down 5.1% premarket and have fallen 9.8% in 2018, while the S&P 500 SPX, +0.21% has gained 7.7%.

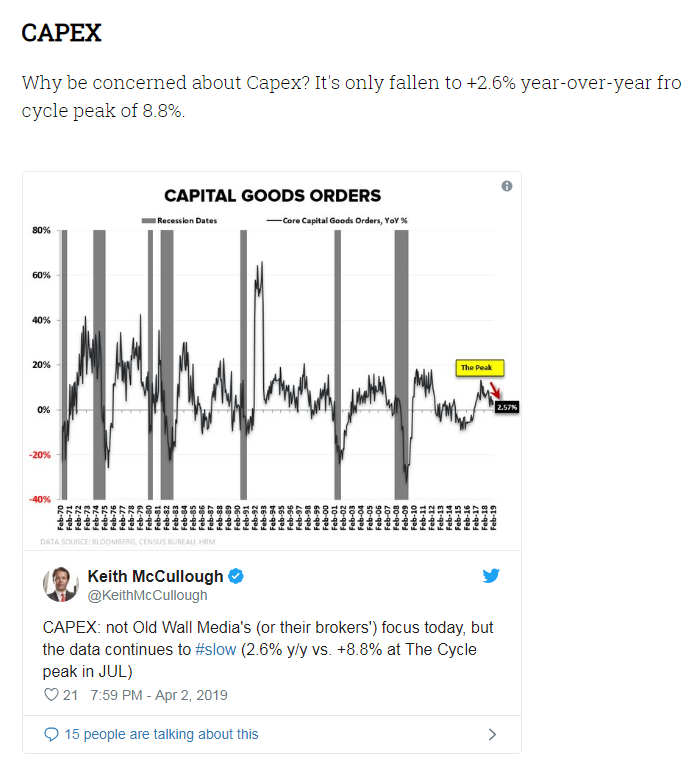

4.U.S. CAPEX Spending Dropping.

What Are Capital Expenditures – CapEx?

Capital expenditures, commonly known as CapEx, are funds used by a company to acquire, upgrade, and maintain physical assets such as property, buildings, an industrial plant, technology, or equipment.

CapEx is often used to undertake new projects or investments by the firm. Making capital expenditures on fixed assets can include everything from repairing a roof to building, to purchasing a piece of equipment, to building a brand new factory. This type of financial outlay is also made by companies to maintain or increase the scope of their operations.

Put differently, CapEx is any type of expense that a company capitalizes, or shows on its balance sheet as an investment, rather than on its income statement as an expenditure.

https://www.investopedia.com/terms/c/capitalexpenditure.asp

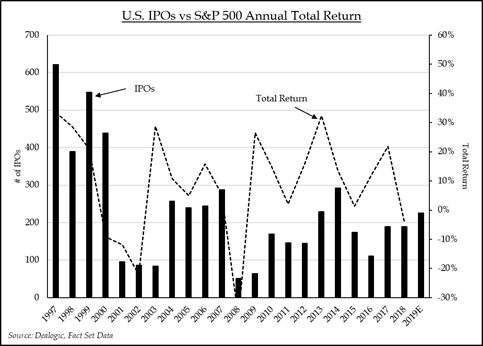

5.The IPO Canary is Still Singing

- Published on April 2, 2019

While investors were lamenting the inversion of the mid-section of the treasury yield curve late last week, traders on the floor of the NYSE were celebrating the revival of denim. The traders’ fashion statement was in honor of the return of Levi Strauss (LEVI) to the public marketplace. The company, which was founded in 1873, and was publicly traded between 1971 and 1985 before being acquired in a leveraged buy-out, is one of the high-profile new issues to hit the public marketplace this year. Ride-hailing companies Lyft and Uber are expected to make their public market debuts in the coming weeks, as are high profile sharing-economy darlings, WeWork and AirBnB. In fact, the 2019 backlog of IPOs has been growing both in terms of the total number of companies going public, and the total dollar amount of new capital expected to be raised. According to a report from Renaissance Capital, 226 private companies are now planning to list on U.S. exchanges this year. The successful float of these new issues would be a bullish sign for the stock market, as a robust IPO schedule is often a good measure of underlying market health and for investor risk appetite. Of course, conversely, the IPO tap can be turned off quickly should market conditions erode.

The past decade has not been particularly active for new issues. Low interest rates and abundant capital available to private companies, combined with the regulatory burden and high cost of being public, have discouraged management teams from pursuing the public path. In fact, the total number of publicly traded companies listed on major U.S. exchanges has fallen from close to 8,000 in 1996 to near 4,500 in 2018 as the trickle of new issues failed to keep pace with de-listings, public company combinations, and private equity take-outs. Corporate share repurchase activity has further reduced the size of the public float of available shares. We calculate that the total number of S&P 500 company common shares available to trade has fallen by 10.4% since 2011. This contraction in publicly available shares has likely been an important contributor to the bull market in stocks. Equity investors simply don’t have abundant supply from which to choose.

In frothy markets, a persistent supply of new shares can result in competition for capital, and in many cases has signaled market tops. But given the dearth of new issue activity over the past decade it is likely that this year’s introduction of new supply will be well received. Significant outflows from stock funds and into bond funds experienced during the past three years, and nine-year high cash levels in money market funds, suggest there is ample capital available for investors to deploy and/or reallocate for favored new issues. So long as the broader market remains in a welcoming mood, IPO activity should remain robust through 2019. The slowing global economy is giving stock investors plenty to worry about. But, so far, the new-issue business is flashing the “all clear” signal. The IPO “canary in the coal mine” is singing loudly. We would be wise to watch that bird for any signs of laryngitis.

Terry Gardner Jr. is Portfolio Strategist and Investment Advisor at C.J. Lawrence. Contact him at tgardner@cjlawrence.com or by telephone at 212-888-6403.

https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/ipo-canary-still-singing-32519-terry-gardner/

6.German DAX Hit 201 Lows.

German ETF

German Rates Touching 2018 lows

German Rates Touching 2018 lows

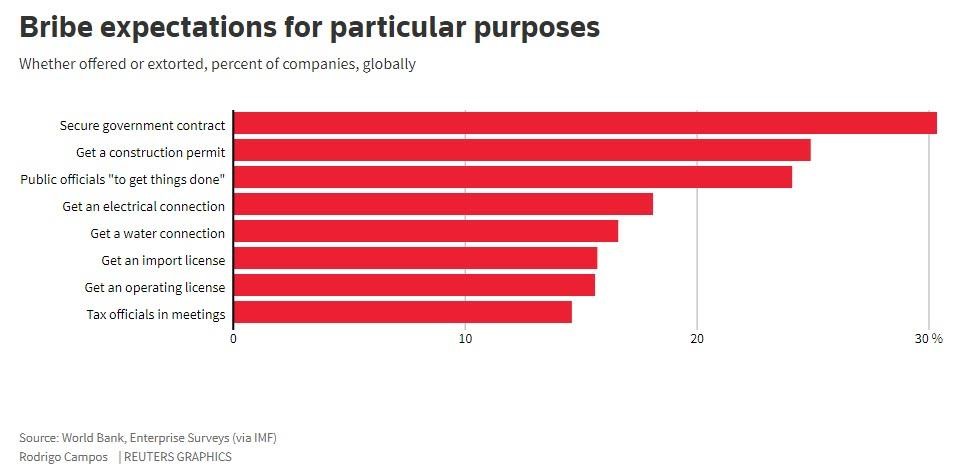

7.Source of Bribes in Emerging Markets.

8.What Goes Into the Development of Greatness?

A new book gives hints about what it takes to make it to the top.

Source: Agnieszka Radwańska at 2008 US Open by Charlie Cowins (CC BY 2.0)

What makes someone with early potential develop that talent in a way that results in high performance or greatness?

A new volume, The Psychology of High Performance: Developing Human Potential into Domain-Specific Talent, edited by Rena F. Subotnik, Paula Olszewski-Kubilius, and Frank C. Worrell, addresses that question by examining outstanding performance across five different domains: academic disciplines (mathematics and psychology), arts production (culinary arts and drawing/painting), arts performance (dance and acting), professions (medicine, software engineering, and professional teams), and sport (golf and team sports).

The book was, in part, inspired by a famous study by Benjamin Bloom and colleagues in 1985, which retrospectively examined the trajectories of world-class athletes, artists, scholars and professionals. That work, the authors write, “remains a valid and elegant reporting of the developmental stages of instruction experienced by his study participants. What was missing … is an explicit description of psychosocial dimensions of eminent achievement.”

The study of expertise has expanded in recent years to examine similarities and differences across multiple domains (see the Journal of Expertise), and this edited volume brings together scholars across various disciplines. Rena, Paula, and Frank kindly responded to three questions regarding their new book.

What have we learned since Bloom’s original contribution on the psychology of high performance?

Ironically, one of the major things that we have learned since Bloom’s (1985) study is how much he got correct. The importance of looking at talent withindomains; providing the right resources both within and outside of school; the importance of the family, especially in the earliest years; the right teachers and mentors at particular stages on the developmental trajectory in a domain; and a community of learners are still key factors in the advancement of high performance.

Since 1985, we have since learned that psychosocial skills and insider knowledge interact with ability to enhance the likelihood of progress to the next level of talent development, and we do have some ideas about which psychosocial skills matter broadly across domains.

We still need to identify psychosocial skills unique to domains and who is best placed to convey these skills and knowledge. Also, we have little to go on regarding developmental benchmarks for talent development, largely because we assume that present performance is the best predictor of future performance—but it may be that present performance is not the sole predictor. A better predictor may be the capacity to develop and maintain critical psychosocial skills. For example, what happens to a talented individual who loses passion for the domain, stops practicing intensely, or is unable to focus?

What are the commonalities for talent development when considering multiple domains?

All domains change over time in response to societal demands. For example, medicine has needed to increase sub-specialization and pay more attention in training protocols to interacting and communicating with patients. Aesthetics within fields of performance also change and as a result, preparation changes (witness that in the education of artists, the basic skill of drawing has become optional in the curriculum and preference is given to learning what you need to know to do the art you want to do).

Commonalities across talent development domains can be divided into several categories. The first is the personal category. In addition to domain-specific ability and creativity, passion, persistence in the face of failure or setbacks, and engaging in the work of the discipline or field over time are useful across domains.

The second category is environmental. Social, emotional, and financial support are critical. Even in domains where the tools or equipment that is required is relatively inexpensive, the resource of time is key, and time is dependent on a certain amount of fiscal resources.

The third factor is chance, which involves both the personal and environmental. The individual developing talent needs to be on the lookout for opportunities and ready and willing to take up opportunities as they arise. There are a lot of talented individuals aiming for the top and typically there are more talented individuals than there are opportunities.

It is important to note that domains differ in important ways as well. For example, talent trajectories begin, peak, and end at different times. And within domains, there are early and late specialization fields, those that focus more on teamwork and others that are more individual, those that expect large commitments to education and those that do not, and those that require a great deal of disciplined or deliberate practice and those that require less.

The next steps for the field will be to categorize these similarities and differences based on research and the best practices presented in this book and translate this information into a testable model.

article continues after advertisement

What can we learn from talent selection and development from sports that has the potential to be applied in academic settings?

Sports provides several key lessons. First, the domain of sport relies more on sport-specific criteria than do academic fields. They use actual performance as a selection tool. Individuals are asked to play the sport, often with other equally talented athletes who are trying out, and those who perform best are selected. Teachers (coaches) do the selection with pretty good accuracy.

Second is the importance of ongoing disciplined practice. We use the term disciplined rather than deliberate practice because the nature of the “practice” that one needs to engage in to succeed in physics or acting may be very different than the deliberate practice required in sport, but it is still practice in the discipline.

Sport has long recognized the importance of psychosocial skills like coping with performance anxiety—particularly at the elite levels of competition. Sports take place in front of audiences where one has supporters and individuals who are not rooting for you and you have got to learn to be able to “shut out” distractions and get the job done. Similarly, games are played almost weekly or even more frequently, and athletes have got to put their best selves on the field or court on every occasion. Thus, an athlete is trained to “pick oneself up” after losses, understand the lessons the loss provides, and move forward to try to win the next game. Sports psychologists are integrated into this important component of training. We leave the development of these skills to chance for academically talented individuals, but we could place more of a focus on developing them.

article continues after advertisement

Sport also seems to have many different avenues for gaining experience in the early years—through school teams, park district activities, club sports, and so on. These opportunities are open to all children and get more selective as they progress. In other words, “on ramps” are readily available. Parents know and accept the idea of starting young children with exposure and progressing to increasingly more selective and competitive opportunities. We do not have such “on ramps” in academics and parents do not have the same knowledge or acceptance of the idea.

However, we argue that many of the advantages of sport come with it being a performance domain, and other performance domains such as elite music performance also offer useful lessons for academic domains. As in sport, in developing elite musical talent, there are explicit criteria for selection based on performance, and diminished reliance on abstract tests. Teachers are often practicing professionals and provide individualized instruction – much of the talent development work is conducted one-on-one. Teacher selection is also key and sometimes more important than the reputation of the music institution. And beyond one-on-one lessons, there are master classes sharing instruction with all the students of one teacher. Additionally, for a student to progress, he or she needs to pass muster every year in front of the whole department. Finally, there are “Reality 101” classes requiring students learn how to behave in professional environments, how to handle stress, how to get an agent, and other practical skills required to facilitate success. These skills would also be useful in academic domains and universities are now beginning to have classes on succeeding in academia or translating your doctoral degree into success outside the academy.

Photo credit: Agnieszka Radwańska at 2008 US Open by Charlie Cowins (CC BY 2.0)