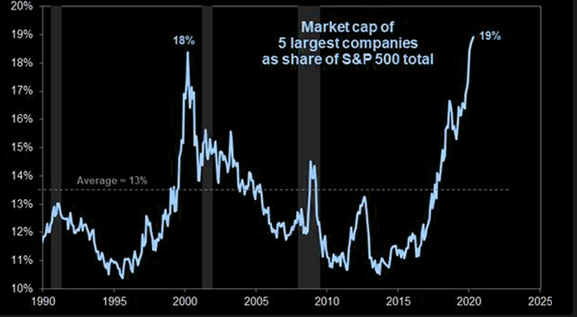

1.Market Cap of 5 Largest Companies Equals Record 19% of S&P

Bloggers note we now have New highs for concentration at the top as measured by the market cap of 5 largest S&P companies as a % of S&P500 (as per yesterday)

From Dave Lutz at Jones Trading

2.The S&P 500 just posted the most daily swings of 3% or greater in more than a decade—even as the stock market hits a 5-week high

The S&P 500 also booked its 38th session gain of at least 1% this year on Tuesday, surpassing last year’s total

U.S. stocks are attempting to recover from their most recent lows of late March, but the recent market gyrations, even with Tuesday’s positive swing, highlight why this coronavirus-stricken market is one of the most volatile since the 2007-09 financial crisis.

On the bright side, the S&P 500 index SPX, +3.05% finished trade up 84.43 points, or 3.06%, at 2,846.06, marking the broad-market index’s highest level since March 10, when fears about COVID-19 were buckling the market. However, Tuesday’s 3% moves marks the 23rd move of at least 3% in either direction for the index, matching such moves in all of 2009, according to Dow Jones Market Data.

The S&P 500 on Tuesday also booked its 38th session gain of at least 1% this year, surpassing last year’s total

Tuesday’s rally also brought the Dow Jones Industrial Average DJIA, +2.39% to its highest level since March 10 and the nearly 4% advance for the Nasdaq Composite Index COMP, +3.94%, on the back of gains in technology-related behemoths Amazon.com Inc. AMZN, +5.27%, Netlfix NFLX, +4.24% , Google-parent Alphabet Inc. GOOG, +4.24% GOOGL, +4.52% and Tesla Inc. TSLA, +9.05%, helped the equity gauge exit the bear market that it entered on March 12.

Bullishness in the market had been all but crushed last month, but appears to be resurfacing on the basis of hope that the worst of the viral outbreak has passed and economies throughout the world, including 10 states in the U.S., are contemplating restarting business activity that has been nearly frozen to limit the spread of the deadly infection from the novel strain of coronavirus.

However, the outsize moves in the market and a still-elevated level for Wall Street’s fear gauge, the Cboe Volatility Index VIX, 7.89%, implies that it will be a bumpy ride for bulls and bears alike. The VIX was at 37 Tuesday afternoon, far from its peak above 80 last month, but still above its historic average at 20.

The likely turbulence ahead may intensify the fervor over one of Wall Street’s favor parlor games: wagers on whether the stock market has reached a durable bottom.

All this said, the clear fact that shouldn’t be ignored is that more than 16 million Americans (and counting) have lost their jobs over the past three weeks, amid the recession wrought by a public-health crisis that has sickened two million people and claimed the lives of more than 120,000 world-wide, according to data aggregated by Johns Hopkins University.

Ken Jimenez contributed to this article

3.Crude Oil….Demand– In volume and percentage, the fall exceeds the collapse of 1979 to 1983. It occurred over four weeks, not four years.

WSJ

Global demand for crude is normally around 100 million barrels a day. Estimates of the decline vary widely and change daily, but most put current demand at 65 million to 80 million barrels a day. In volume and percentage, the fall exceeds the collapse of 1979 to 1983. It occurred over four weeks, not four years.

‘This is uncharted’

“Since humans started using oil, we have never seen anything like this,” said Saad Rahim, chief economist at Trafigura Group Pte. Ltd., a Singapore commodity-trading company that estimates demand at 65 million to 70 million barrels a day. “There is no guide we are following. This is uncharted.”

By Russell Gold, Benoit Faucon and Rebecca Elliott

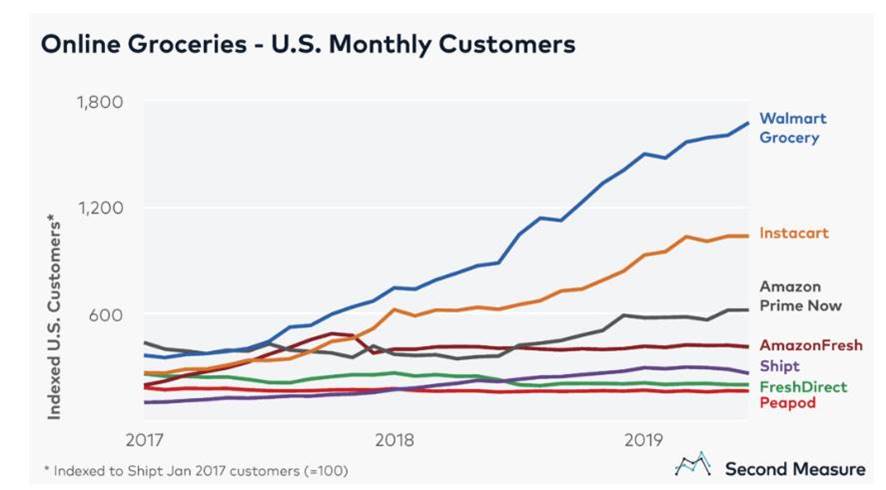

4.Walmart generated $900m in online grocery sales last month

Walmart tops US online grocery market, with 62% more customers than next nearest rival

Sarah Perez@sarahintampa / 10:58 am EDT • August 13, 2019

5.Cost to Insure Investment Grade Debt Spiked But Nothing Like 2008.

https://www.ft.com/content/f013c18e-649c-11ea-b3f3-fe4680ea68b5

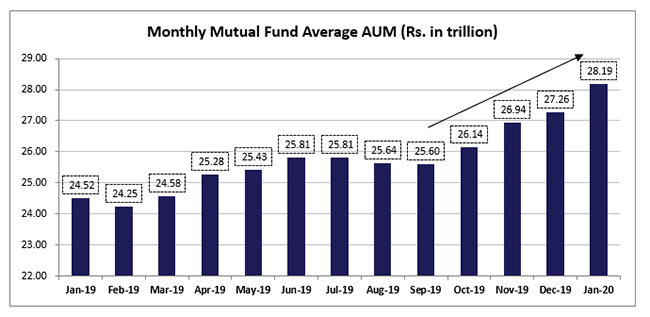

6.March Set a Record for Monthly Outflows From Active Mutual Funds at $356B

March set a record for monthly outflows from active mutual funds, at 356 billion. The estimated 10 billion in lost revenue from March alone is more than the annual revenue of the entire ETF industry. -Bloomberg

6:29 PM · Apr 6, 2020·Twitter for iPhone

Mutual Funds $28T Jan 2020

7.Crude Tests 20 Year Low

$20

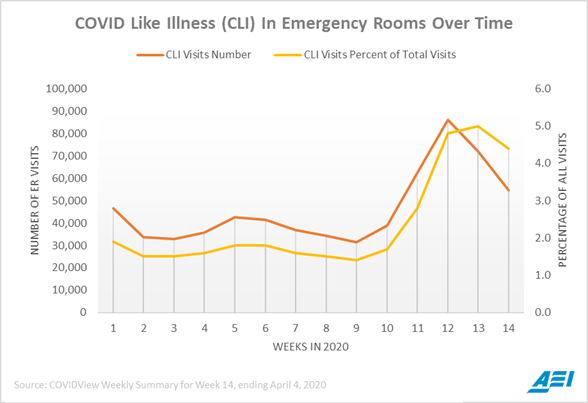

8.Emergency Room Visits COVID

9.Bursting the Bubble: Why Sports Aren’t Coming Back Soon

The NBA, NFL and MLB are dreaming up ways to play amid a pandemic, with talk of isolating players in Arizona or Las Vegas or maybe on the moon. It all sounds great, until you talk to people who actually know science.

The proposals multiply almost as fast as the coronavirus: The NHL can play in North Dakota! The NBA can play on a cruise ship! MLB can play in a biodome! The NFL can play in its stadiums, with 70,000 fans packed in!

These are fun thought experiments, at least as good a way to spend time in isolation as watching Tiger King. And everyone wants to believe we will be buying peanuts and Cracker Jack this summer. But fans deserve a reality check: According to the experts—medical experts, not the money-making experts in league offices—we will not have sports any time soon. And when we do, we will not attend the games.

Most of these ideas are essentially the same: The players live in quarantine, shuttling from the hotel to the stadium, for the duration of the season. They undergo daily COVID-19 tests. They bring joy to a terrified country. That seems reasonable on the surface. But look closer.

First, let’s do away with the suggestion, put forth by President Donald Trump, that football season could go on as normal, beginning on time in September and unfolding in front of crowded stadiums.

“We will not have sporting events with fans until we have a vaccine,” says Zach Binney, a PhD in epidemiology who wrote his dissertation on injuries in the NFL and now teaches at Emory. Barring a medical miracle, the process of developing and widely distributing a vaccine is likely to take 12 to 18 months.

Until the vast majority of the population is immune to COVID-19, the disease the virus causes, any gathering as large as an NFL game risks setting off a biological bomb. That may sound like hyperbole, but that’s the exact phrase a doctor in Bergamo, Italy’s hardest hit city, used to describe a Feb. 19 soccer match between hometown Atalanta and Spain’s Valencia, which super-charged the virus’s spread.

O.K., but what about empty stadiums?

“The idea of a quarantined sports league that can still go on sounds really good in theory,” says Binney. “But it’s a lot harder to pull off in practice than most people appreciate.”

Conversations with experts painted a picture of what exactly it would take to make these sports vacuums a reality. Before any of this can begin, every person who would have access to the facilities will need to be isolated separately for two weeks to ensure that no infection could enter. That’s players and coaches, athletic trainers and interpreters, reporters and broadcasters, plus housekeeping and security personnel. No one can come in or out. Food will have to be delivered. Hotel and stadium employees will have to be paid enough to compensate for their time away from their families. Everyone onsite will have to be tested multiple times during this initial period.

That brings us to the question of testing. At the moment, screening is scarce enough that many healthcare facilities cannot even clear their employees. Asymptomatic professional athletes are not high on anyone’s priority list. But here Carl Bergstrom, an infectious diseases expert at the University of Washington, offers some hope. Testing is not technologically difficult, he says. There are supply chain issues—we will eventually run out of the long Q-tips required for the nasopharyngeal swab, for example—and questions of bureaucracy, but he is cautiously optimistic that we might have ubiquitous COVID-19 testing by the end of May.

All right, so the 14-day period is over and everyone has tested negative at least twice. Now they are allowed to begin spending time around one another—but not too much time. If one person gets it, he or she will begin spreading it immediately, so everyone will have to continue practicing social distancing. That probably means using a new ball for each play. It probably means seating players in stands rather than on benches or in dugouts. It certainly means banning high-fives.

All personnel must continue to be tested daily. We will be unlikely to have enough rapid testing by then, so they will probably have to settle for the tests that take several hours to produce results. That means the testing will probably run a day behind.

Any major sporting event hires ambulances, stocked with EMTs, to idle outside in case of injury. If a player needs treatment by outside medical personnel, even just for a sprained ankle, he or she has left the secure area and will need to isolate for 14 days before returning to it. And, of course, medical resources need to be abundant enough that society can afford to have ambulances and EMTs on call for games, plus doctors and nurses—clad in currently-scarce protective equipment—who can tend to sports injuries.

Minor leagues cannot afford to play to empty stadiums, so you also need a taxi squad of players practicing in isolation in case someone gets hurt. And because players recognize that a championship won under these circumstances will be seen as tainted, expect them to be less likely to play through injury.

After each game, everyone will need to be transported back to the hotel. If the NBA plays in Las Vegas, as has been proposed, the personnel might be able to walk from the court to their rooms. If MLB plays at spring training sites in Arizona, as it is considering, the league will have to hire bus drivers—who will, of course, also have to be isolated. And then once they are back in their rooms, every person involved will have to follow rules. You can’t take your kids to the park. You can’t run to the grocery store. You can’t invite your Bumble match up to your room. These are humans, so the leagues would surely require insurance: That means security personnel (another group that would need to isolate) or invasive cell phone tracking (good luck getting that by the players’ union). If your wife gives birth or your father dies of cancer and you want to be there, that’s another 14-day reentry period.

And ethically, Bergstrom says, “you need informed consent.” That means everyone has to opt in and no one’s paycheck can hang in the balance.

Fine. So no one touches anyone else or goes anywhere. Experts agree that if everything goes perfectly, the leagues could theoretically pull this off. Baseball has the advantage of little in-game contact between players. Basketball and hockey have the advantage of being able to skip ahead to the playoffs and eliminate teams quickly. Football has the advantage of time. Individual sports such as golf and tennis might have the best chance of all, given the smaller number of participants and relative ease of keeping them separate.

But there are a million ways the Jenga stack could fall: What if the person delivering groceries to the biodome walks by someone who coughs on the lettuce and a week later, a player tests positive? Is there an option other than shutting down the whole operation for 14 days?

“No,” says Bergstrom.

And that’s really the end of the conversation. Even if we can start this, we almost certainly can’t finish it. Just look at South Korea and Japan, which both believed they had the outbreak under control and have since pushed back the start dates of their professional baseball seasons. In response to ESPN’s reporting on the MLB biodome scenario this week, former Medicare and Medicaid head Andy Slavitt tweeted, “I’m as big a sports fan as anybody, but this is reckless. Leagues need to follow the science & do the right thing.”

The leagues know how farfetched their ideas are. So do the players’ unions. They continue to explore options because they would be remiss not to. But fans should understand how unlikely this all is.

No one wants to acknowledge how far we are from ordinary life, says Kimberley Miner, a professor at the University of Maine who develops risk assessment for the U.S. Army. “It’s hard to stomach a lot of this information, so it’s not being widely shared,” she explains.

But the reality is that even after we pass the initial peak of infection, the virus is still active. We have already lost more than 16,000 Americans to this disease. Bringing back sports soon would give people a reason to stay inside, a reason to feel hopeful. It would probably also cost more lives.

“If people just decide to let it burn in most areas and we do lose a couple million people it’d probably be over by the fall,” says Binney. “You’d have football. You’d also have two million dead people. And let’s talk about that number. We’re really bad at dealing with big numbers. That is a Super Bowl blown up by terrorists, killing every single person in the building, 24 times in six months. It’s 9/11 every day for 18 months. What freedoms have we given up, what wars have we fought, what blood have we shed, what money have we spent in the interest of stopping one more 9/11? This is 9/11 every day for 18 months.”

The peanuts and Cracker Jack will be waiting for us when sports are ready to come back. Only the virus will determine when that is.

BY STEPHANIE APSTEIN https://www.si.com/mlb/2020/04/10/sports-arent-coming-back-soon

10.The Art of Making Tough Decisions in a Crisis

Here are two processes to help—one from psychology and one from the military.

The global pandemic has forced business owners and leaders to make some very tough decisions. Across the industry, leaders are deciding whether to lay off or furlough workers, cut pay, freeze hiring or cancel important programs and incentives, all while continuing to deliver top-notch service to clients and business partners.

But how do you know if you’ve made the right decision? How much thought should you give to crisis-time decision making? Here are two processes to help – one from psychology and one from the military.

What Psychology Says

Our brains often run on two different tracks when making decisions:

The first one is our intuition or the gut reaction we have to something. It’s a decision you make based on emotion, instinct, and little information. It’s tempting to take a bad stretch at work and decide you will march into the boss’s office, quit on the spot and go start your sure-to-be billion-dollar tech startup, or to move to a warm island.

When I was burning out at work, I fantasized about moving to a warm island all the time. When you’re in this mode, your decisions become automatic and you often don’t give much thought to the exact causes or what influenced the decision. I’m not saying you should never rely on your gut – there are times when you absolutely should – but you must also understand that gut-reactions can be filled with mental shortcuts and biases that can lead you in the wrong direction.

The second track is much more deliberate. The reason why you don’t move to the Bahamas when you’ve had a bad week, I suspect, is that you become more deliberate in your thinking. You start to compare costs and benefits, weigh options and bounce ideas off of other people. While it might be a fun move in the short term, it’s a decision that will have serious consequences long term.

When faced with making decisions in a crisis, psychologists suggest a “think instead of blink” approach, with the following four research-based suggestions:

1. Write down your knee-jerk, gut reaction(s) to the situation and then put it away for a bit. Once you think through the decision, you can revisit your initial impressions and may reconsider given the insights you developed.

2. Seek the opinion of an outsider or an impartial friend, or if you can, try to look at the situation from an objective observer’s perspective. When you’re in the middle of a critical decision, it’s hard to be objective, hence the call to seek an outsider’s opinion.

3. Consider the opposite of your gut reaction and analyze the consequences in your mind. If your first thought is to lay off half of your workforce, consider the opposite and the consequences.

4. If you must make multiple decisions, weigh all of your options at the same time. This type of “joint” decision making is less prone to bias.

The Military Model

Military leaders must make critical decisions all the time in their work. I learned about the Military Decision-Making Process (MDMP) when I worked with soldiers for several years teaching them resilience and stress management strategies.

The MDMP is the military’s checks and balances system for crisis decision making. The MDMP has seven steps, which I’ve translated into “civilian speak” with the help of my friend, Lt. Col. Sylvia Lopez. Let’s walk through each of the steps using the following scenario: You are a senior leader in your organization, and you are considering whether to lay people off for the next month due to the pandemic.

article continues after advertisement

Step 1 – Receipt of “Mission:”: There is a big, complex issue that needs a decision, and it requires other personnel – likely your team. You all need to be on the same page about the exact decision you’re trying to make.

Step 2 – “Mission” Analysis: The team must analyze all of the variables contributing to the end decision. In our scenario, there will be operational issues, PR consequences to consider, budget and economic ramifications, legal issues, and time constraints, to name a few.

Step 3 – Develop Courses of Action: Because it can be tempting (and easy) to get married to your idea, you need to lay out a specific structure for all of your options. You also need to meet the strategic goals laid out by the CEO or senior leadership and explore structured “what if’s.” For example, the CEO might have said to your team, “In thinking about this decision, the best option has to be short-term, involve as few key people as possible, have limited economic impact and there must be a path to quick on-board once the crisis is over.”

Step 4 – Evaluate Each Course of Action: Each leader now separately considers how a decision will impact his or her corner of the world. If you’re an HR leader, you might consider the worker’s comp impact, reintegration messaging and timing, and the structure of severance packages.

Step 5 – Compare Courses of Action: The team reconvenes to weigh the results of Step 4. Will the legal ramifications be given more weight in the ultimate decision because the consequences would be far worse for the organization than a temporary budget hit?

Step 6 – The CEO (or ultimate decision-maker) chooses the course of action to take and/or may create a new course of action for the team to execute based on the findings.

Step 7 – Implement the decision.

My first thought was that this process seems too long for the types of decisions Corporate America must make imminently. When I asked Lt. Col. Lopez about that, she said you could proceed through the steps quickly if the right team is in place, the team is diverse and has the right strengths and the leader is focused and delegates well.

article continues after advertisement

Making critical decisions in times of crisis is hard. You want to slow down knee-jerk reactions, but you also don’t want to be paralyzed by analysis. Hopefully these models give you some framework or structure for reaching the best decision you can make with the information at hand.

Paula Davis-Laack is the CEO of the Stress and Resilience Institute, and she is writing a book about burnout prevention to be published by the Wharton School Press in early 2021.