1. Russia’s Militarization of the Arctic

Business Insider

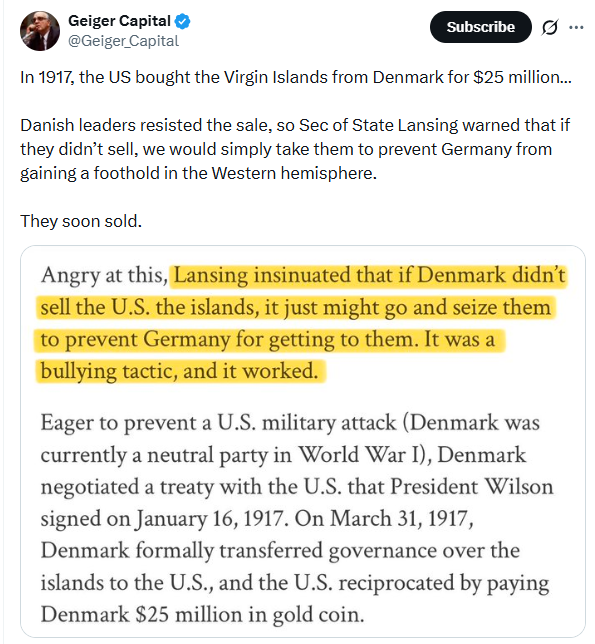

2. Not Political ….Interesting History of the Region

Geiger Capital

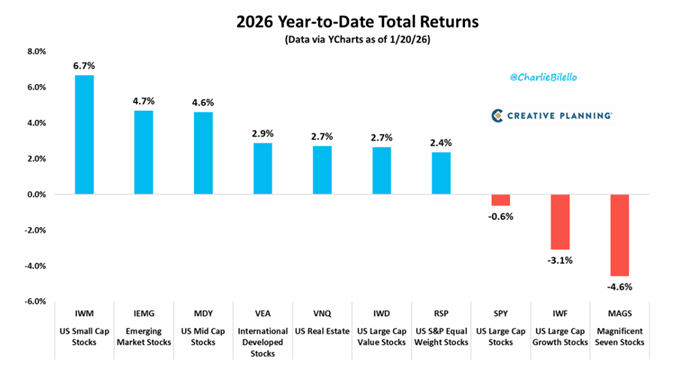

3. 2026 Year to Date Returns..Big Rotation Out of Tech

Charlie Bilello

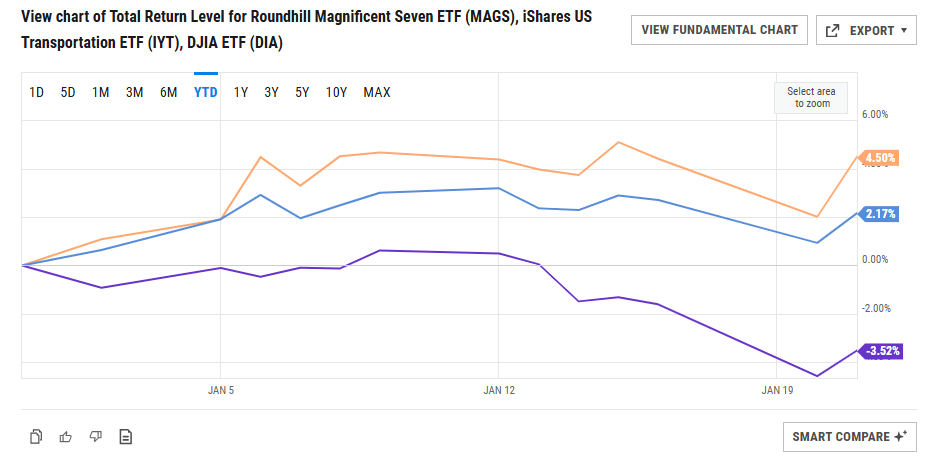

4. 2026 Dow Transports +4.5% Dow Jones +2.20% vs. Mag 7 -3.5%

Ycharts

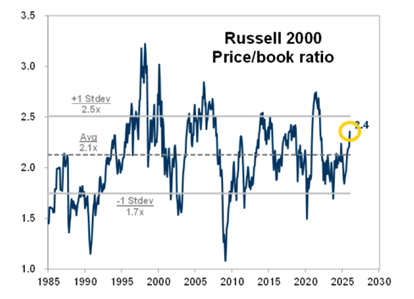

5. The Small Cap Outperformance from Previous Letters Showing Up in Higher Price to Book

Zach Goldberg Jefferies

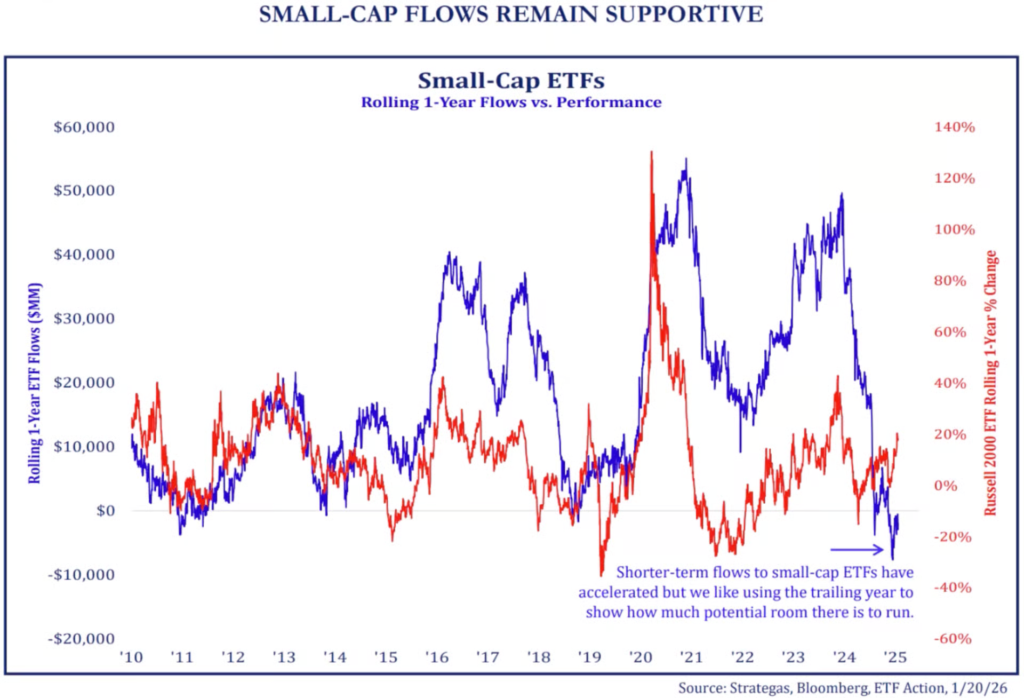

6. Small Cap Stocks Still Seeing Outflows in Last 12 Months

Small cap ETF flows. “If you look at small cap ETFs, all of them together, over the last year there are still outflows”.

Daily Chartbook

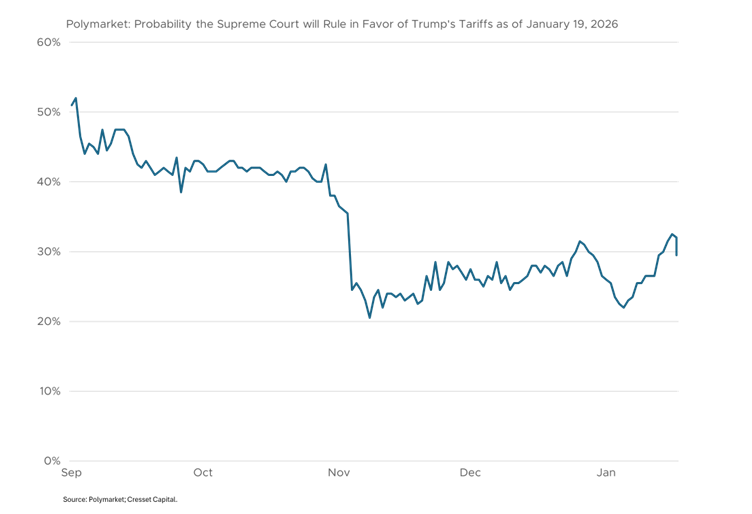

7. Supreme Court Tariff Ruling Odds Polymarket

Cresset

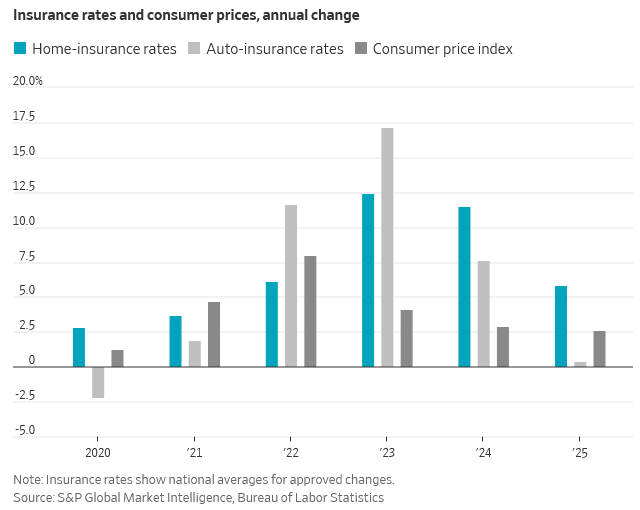

8. Home and Car Insurance Rates vs. CPI

Dave Lutz at Jones Trading

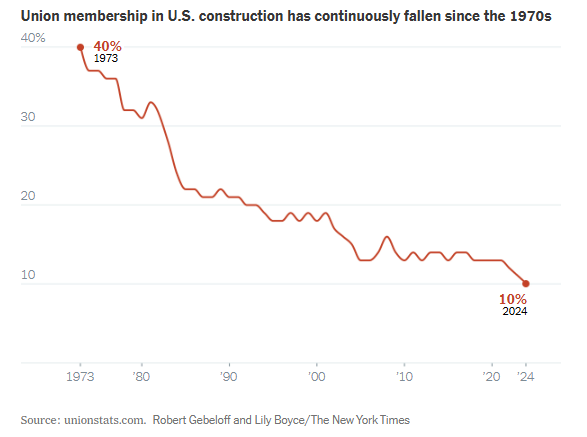

9. The Implosion of American Union Construction Workers

The New York Times

10. The Spreadsheet Trap

Why obsessing over retirement math might be keeping you from the life you say you want

Spreadsheet jockeys, listen up.

There’s a reason you exist. A reason you keep tweaking assumptions, adjusting cells, rerunning Monte Carlo simulations, and debating withdrawal rates deep into the night. And in my opinion, that reason might not be entirely healthy.

I say this as someone firmly inside the personal finance community. I create content here. I spend a lot of time talking about technicalities. Safe withdrawal rates. Inflation assumptions. Asset allocation. How many years you’ll be retired. Whether 70/30 is reckless or 60/40 is outdated. On and on and on.

So this isn’t an attack from the outside. It’s an observation from within.

Because alongside the creators (myself included), there’s a huge group of people quietly hunched over spreadsheets, trying to get the numbers exactly right. Debating who’s correct. Who’s being irresponsible. Who’s being conservative enough. As if precision itself is the prize.

At some point, I think we need to stop.

Not stop caring about money. Not stop understanding the math. But stop believing that more calculation will save us from what we’re actually avoiding.

Because I think this obsession fulfills a need. A psychological need. And that need doesn’t always serve us.

Here are three reasons people become spreadsheet jockeys—and why I don’t think any of them ultimately help.

1. Spreadsheets protect us from the leap of faith

At the core of all this number-crunching is a simple, uncomfortable truth: retirement is a leap of faith.

At some point, no matter how sophisticated your model is, you have to step into an unknowable future. You can’t spreadsheet your way around that. You can only delay facing it.

Markets will do things no model predicts. Black swan events will arrive uninvited. Your health, relationships, interests, and identity will change in ways no spreadsheet cell can capture. The future is not just uncertain—it’s fundamentally unknowable.

And that’s terrifying.

So we respond the way humans often do: by trying to control what can be controlled. We tighten assumptions. Lower withdrawal rates. Stress-test scenarios. Run worst-case projections until we feel safe again.

But here’s the uncomfortable part: safety is an illusion.

No amount of modeling removes the leap. It only postpones it. Eventually, you still have to choose to act without complete certainty. That’s not a failure of planning. It’s the nature of life.

The spreadsheet isn’t wrong. It’s just incapable of giving you what you’re actually asking for: a guarantee.

2. Numbers give us permission to chicken out

This is the one I see most often, and it’s the hardest to admit.

There are people with more than enough money to retire—by any reasonable standard—who stay in jobs they actively dislike. Not because they need the income, but because the spreadsheet says “maybe not yet.”

And if it doesn’t say that at first, they can make it say that.

All it takes is a slightly lower return assumption. A longer lifespan. A higher inflation estimate. A more conservative withdrawal rate. Eventually, the spreadsheet delivers the verdict they’re hoping for: You can’t retire.

Anxiety relieved.

Back to work they go. Miserable, but comfortable. Unfulfilled, but certain.

Retirement sounds great in theory. Leaving an identity behind? Much scarier. Letting go of a role where you know who you are, what you’re good at, and how you’re valued? That’s a real loss. And spreadsheets provide a socially acceptable excuse to avoid grieving it.

People say they want freedom. What they often want is freedom without risk, identity loss, or discomfort. And that version doesn’t exist.

So instead, they optimize numbers until inaction feels responsible.

3. Numbers are easier than meaning

Here’s the deepest reason spreadsheets are so seductive: they let us redefine winning.

If winning is having the right net worth, the lowest withdrawal rate, or the most conservative plan, then the game becomes measurable. Definable. Clean.

And crucially, it keeps us out of a much harder arena.

Because the real questions—the ones money is supposed to support—are messy and undefinable. What do you want your days to look like? Who do you want to spend them with? What feels meaningful now that achievement and accumulation aren’t the point?

Those questions don’t have formulas.

So instead, we convince ourselves that getting the numbers right is the purpose. That financial optimization is the end goal, not the tool. We stay outside the arena, pencil in hand, erasing and recalculating, while life happens elsewhere.

Spreadsheets allow us to avoid vulnerability. Avoid experimentation. Avoid failure. Avoid meeting people doing hard things. Avoid discovering that the life we thought we wanted might not actually satisfy us.

They give us something to polish instead of something to live.

Putting the calculator down

Let me be clear: understanding your finances is healthy. Running the numbers is responsible. You should know where you stand. You should plan. You should model scenarios.

But perfection is not the goal. Adequacy is.

At some point, the marginal benefit of another spreadsheet iteration drops to zero. Beyond that point, you’re no longer planning—you’re hiding.

Money is a means, not a moral achievement. Wealth is not proof that you lived well. It’s only useful if it creates space for you to actually show up to your life.

So yes, spend some evenings with your spreadsheets. Learn the math. Build confidence. But then, this is the important part, put the calculator away.

Go live.

Believe it or not, becoming a spreadsheet jockey can be an excuse. An excuse to delay the very things money is supposed to enable: freedom, connection, curiosity, and meaning.

The numbers don’t need to be perfect.

Your life doesn’t either.