1. Utilities Not Acting Defensive in Last Week’s Pullback

Utility Index About to Make New Lows as S&P Sold Off

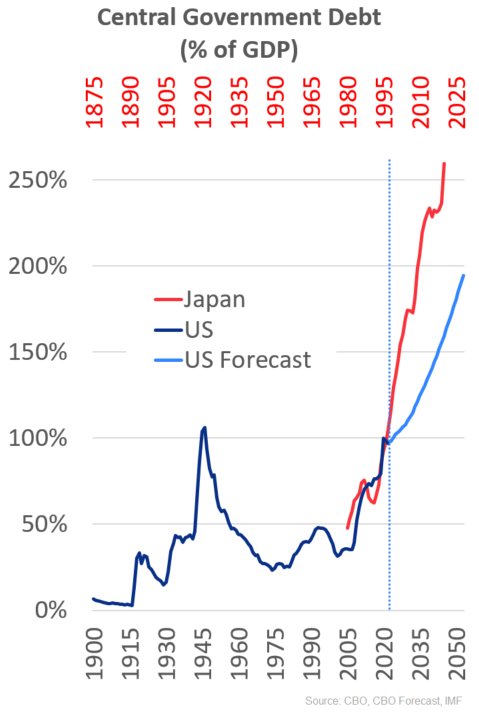

2. U.S. Government Debt

Dorsey Wright However, these persistent deficits, combined with an aging population which is expected to add to Medicare and social security costs, have some forecasting US debt will increase to 200% by 2050. That’s not unheard of – Japan was in a similar situation back in the 1990’s (red color in chart below), and they now have debt to GDP over 250%.

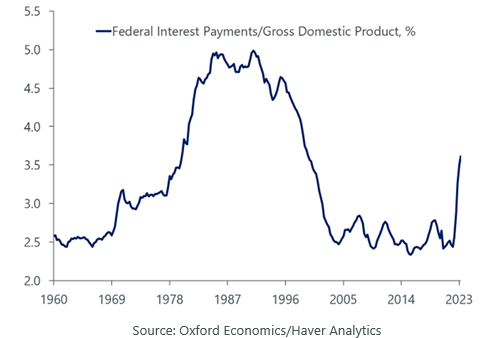

The problem with all that debt is that, just like all of us, the government needs to pay interest to its lenders. Japan has managed to continue deficit spending to support their economy because their interest rates are so low. Luckily, for now, the average interest rate the US government needs to pay on debt is also still pretty low. But, if inflation doesn’t recede, and debt keeps growing, it’s possible net US government interest costs could more than quadruple to 7.2% of GDP by 2052, That would soak up nearly 40% of federal revenues – compared to around 10% today – which would necessitate much higher taxes or much lower government spending. Or both.

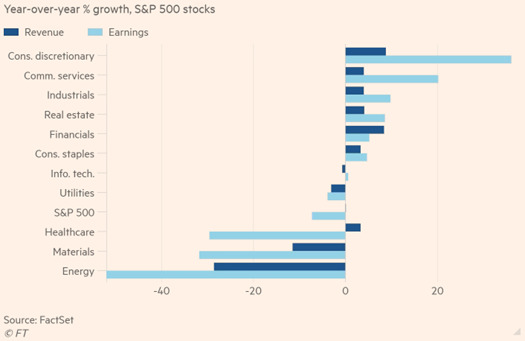

3. S&P Revenue vs. Earnings Growth by Sector

4. Bekshire Another Name Right at Previous Highs

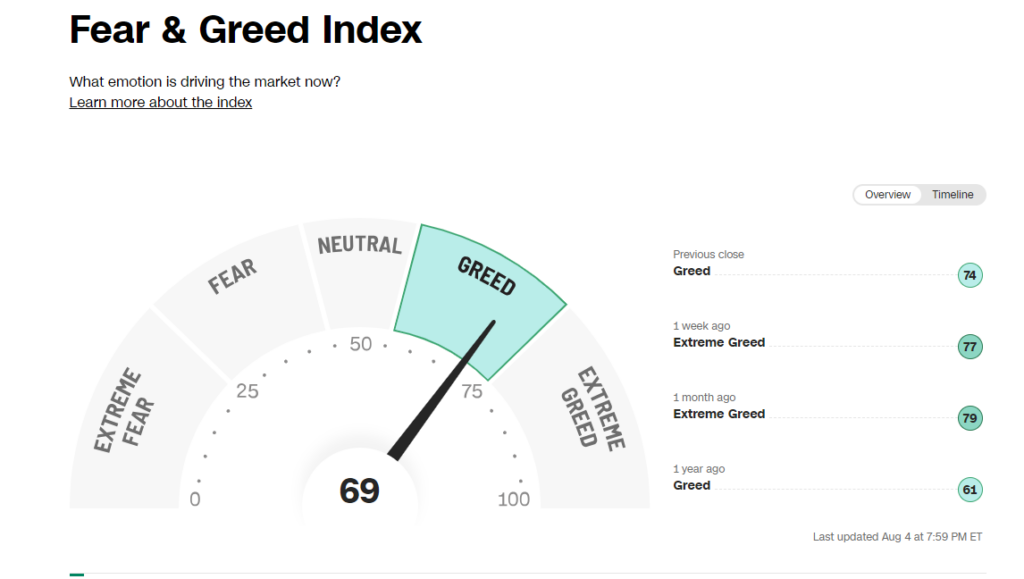

5. Fear and Greed Index Update Going into Weak Seasonality

https://www.cnn.com/markets/fear-and-greed

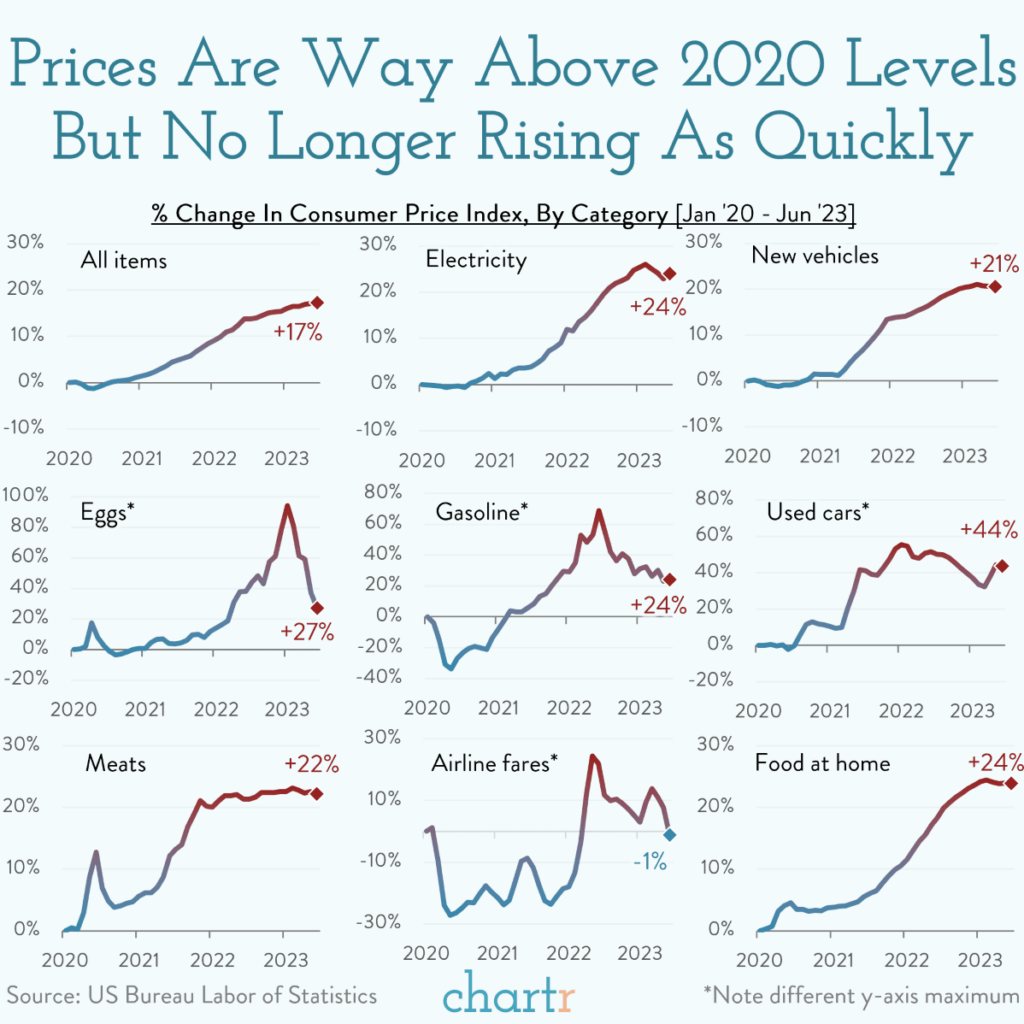

6. Prices Since Covid

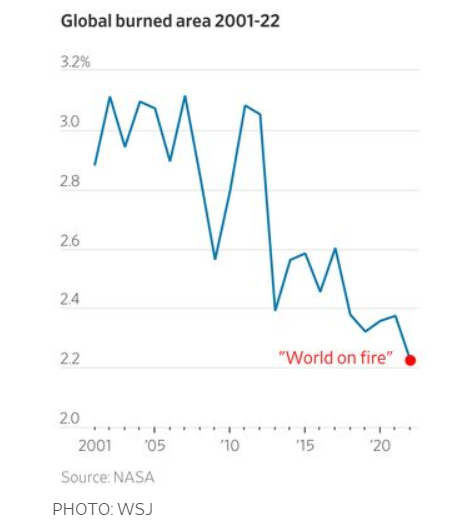

7. Global Burned Areas Going Down Since 2000

WSJ By Bjorn Lomborg For more than two decades, satellites have recorded fires across the planet’s surface. The data are unequivocal: Since the early 2000s, when 3% of the world’s land caught fire, the area burned annually has trended downward. In 2022, the last year for which there are complete data, the world hit a new record-low of 2.2% burned area.

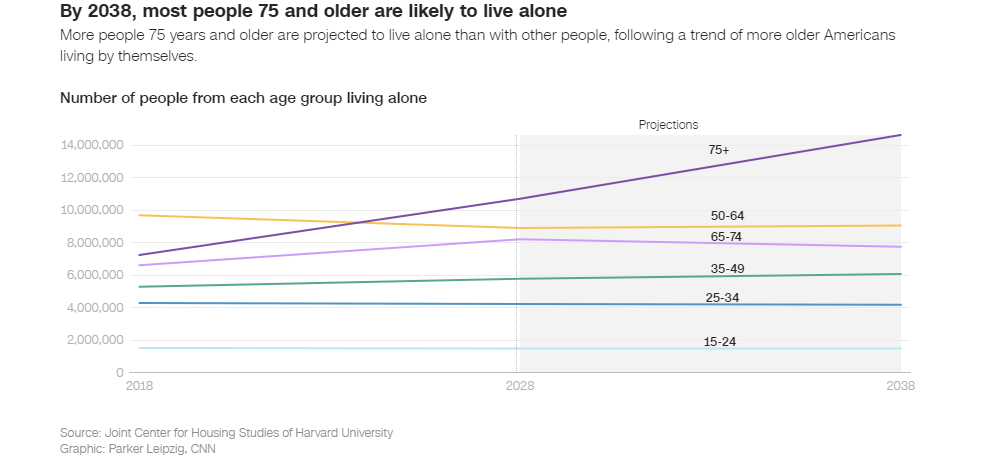

8. More Data on Americans Living Alone

By Catherine E. Shoichet and Parker Leipzig, CNN

https://www.cnn.com/2023/08/05/health/boomers-divorce-living-alone-wellness-cec/index.html

9. College Football-Morningbrew

Over the past few days, college football has undergone a shake-up that further obliterated traditional geographic rivalries, left a once-proud conference on its deathbed, and cemented the formation of a handful of national superconferences—all in the pursuit of TV riches.

The moves reflect the inevitable professionalization of college football, one of the only university athletic products that can command billions of dollars for television broadcast rights.

Here’s what went down:

- Oregon and Washington defected from the Pac-12 for the Big Ten, joining their West Coast peers USC and UCLA in the once-Midwestern-focused conference that will soon have 18 teams from coast to coast.

- Arizona, Arizona State, and Utah said they would also leave the Pac-12 for the Big 12, a decision Colorado made two weeks ago.

- The 108-year-old Pac-12 is teetering on the verge of collapse with just four schools remaining: Stanford, Cal, Oregon State, and Washington State.

If you hate this, blame TV

The Big Ten and Southeastern Conference (SEC) have recently secured mega TV deals that will pay their members handsomely…and the Pac-12 has not. It’s that simple.

The SEC inked a $3 billion deal for 10 years with Disney beginning in 2024, while the Big Ten reached a mammoth agreement with Fox, CBS, and NBC worth up to $7.5 billion over seven years. The Pac-12 has been trying to strike a deal with Apple TV+ to stream its games, but the potential payout for schools was not enough to stop the exodus.

- The Big Ten sent $58 million to each of its schools during the 2021–22 fiscal year, according to tax records, and that number will only grow under its new TV deal.

- Under the Apple deal, Pac-12 members would receive $30 million…on the high end of the range.

Big picture: “The old question—how long would it take TV money to destroy college football? Maybe we’re here. Maybe we’re here,” the head football coach at Washington State mused last Thursday. And whether or not you agree that conference realignment has “destroyed” college football, it has certainly dismantled the regional distinctiveness of each conference that gave the sport its magic.

Screenshot via @FieldYates/Twitter

https://www.morningbrew.com/daily

From Dave Lutz at Jones Trading SHOW ME THE MONEY– Florida State University is working with JPMorgan Chase to explore how the school’s athletic department could raise capital from institutional funds, such as private equity – PE giant Sixth Street is in advanced talks to lead a possible investment, Sportico Reports. Institutional money has poured into professional sports in recent years, from the NBA and global soccer to F1 and golf, but this would break new ground by entering the multibillion-dollar world of college athletic departments.

The school is considering a structure similar to many of those pro sports investments, where commercial rights are rolled into a new company, the private equity fund invests in that entity, and then recoups its money via future media/sponsorship revenue. That’s how Silver Lake structured its investment into the New Zealand All Blacks rugby team, and how CVC organized its $2.2 billion Spanish soccer deal with LaLiga.

10. Sportswriter Sally Jenkins details what elite athletes can teach the rest of us-Yahoo Finance

Kerry Hannon·Senior Columnist Sally Jenkins’ father, Hall of Fame sports writer Dan Jenkins, once told her: “A lot of people are afraid to win.”

For years, The Washington Post sports columnist didn’t know what he meant until she mentioned the line to her late friend, Pat Summitt, the winner of eight women’s basketball championships at the University of Tennessee.

“Some people don’t want to keep score, because most people are afraid to go all in,” Summit told her. “They’ll have to say, ‘That’s the best I can do.'”

That’s not true of elite athletes, who Jenkins has spent more than three decades following.

She remembers Charles Barkley saying when he was a young all-star NBA player for the Philadelphia 76ers: “I realize I’m never going to be perfect, but as long as you strive to, at least you’re going to get better.”

The Chicago Bulls’ Michael Jordan (23) shows he’s still friends with the Phoenix Suns Charles Barkley as they get set to play Game 6 of the NBA finals in Phoenix, June 20, 1993. (AP Photo/John Swart)

And there’s Tom Brady, who Jenkins said was a faster runner at 42 than at 22 when he came out of college.

“What separates these elite athletes, the Hall of Famers, is that they try to get better every day, not by 20%, but just 1% or 2%,” Jenkins said, quoting Tom House, a well-known football throwing coach.

“The rest of us kind of plateau and stop,” she said. “We get pretty good at something and then we don’t work for the 1% to 2% improvement, but the 1% to 2% improvement over time can be really significant.”

Jenkins explores the principles behind their success in her new book, “The Right Call: What Sports Teach Us About Work and Life.” Here’s what she shared with Yahoo Finance.

Excerpts edited for clarity:

Sally, why did you write this book?

You see a lot of hero worship and a lot of kind of idolatry of athletes. And if you are a sportswriter for long enough, you come to the conclusion that people often admire them for the wrong things. They are beautiful; they do magnificent things, but they’re just as flawed as you or me. And so the nagging question for me for many, many years has been, what’s really exportable from these people? What are we supposed to be really learning from this? Apart from awe.

What can sports teach us about work?

The more important things that they teach are basic resilience in the face of setbacks. The champions that really succeed often weren’t identified as the most talented kid on the field when they were small. My favorite thing in the book might be the fact that 27 members of the Tampa Bay Buccaneers Super Bowl winning team were rated two stars or less by talent evaluators in high school. So I think the first and most important thing we should take is that talent is an absolute fractional factor in real success. I won’t say it’s meaningless, but I will say it’s next to meaningless compared to all the other things that athletes and coaches do that make them worth watching and make them great.

Your book is built around the seven fundamentals of great decision-making. Could you give us a snapshot of why those are important in the our work?

Conditioning is not just being in good shape. It is the messaging system between your brain and your body, so it can work more efficiently. Conditioning is really big in decision making because your brain robs your muscles of the energy to function. There’s a million different neurological studies out there that show people’s judgment really changes, and they get more erratic, when they’re gassed.

You have to practice with a purpose. Deliberate practice means detailed work on your weaknesses and then practicing on those weaknesses and making measurable improvement. It’s actually understanding, say, that your left foot is weaker than your right.

Peyton Manning’s feet get very uneven under pressure. And he tended to throw from a less stable position when defensive linemen were coming at him below the knees. And so coaches would hurl sandbags at his feet to try to get his feet set in the proper position. That leads to a good arm throw.

The rest of us tend to run around our backhand. Athletes don’t do that. They make their left hand as strong as their right, and that is a critical separator between them and people who don’t win things, or people who don’t go about their lives as purposefully.

What the really great coaches understand, even so-called disciplinarians, like Pat Summitt or Mike Krzyzewski, is that you actually have to ask people to discipline themselves, and you have to select people who are willing to discipline themselves. The last thing a leader wants to do is waste a whole lot of time trying to persuade someone who’s unwilling to adopt basic standard habits so that you can move on to more interesting work.

One thing Peyton Manning told me was that Tony Dungy had incredibly disciplined teams, but Tony Dungy never raised his voice. And Peyton said that Dungy wasn’t going to have anybody in the room who he had to ask to be on time. You were either interested enough in the endeavor to be on time or you weren’t going to be there.

The Right Call

What’s next?

Candor is the honesty to look at yourself and look at your teammates and talk frankly about what’s going on in your performance or in an organization’s performance. And do it in a way that is diagnostic, but not blaming or accusatory. Blaming doesn’t lead to good outcomes. People can wind up clouding an event with an excuse or rationalization, and you never get at what’s really happening.

Culture is so hard to define, but Steve Kerr was really helpful on that one because he’s built such a great one at Golden State. Golden State Warriors’ culture is a very joyful culture. Kerr basically wanted it to seem to just play like kids play.

The first thing you see when you go to a Warriors practice is you see balls flying all over the place in the gym. And instead of being in these regimented warmup lines and stuff, you see the Warriors are doing trick shots and laughing and horsing around in some ways. There’s music blasting from the speakers. There’s real high energy and a lot of laughter, and that’s one way Kerr aligns everything he’s trying to do with Golden State. He wants them to play very fast and loose basketball, and he understands, as he put it to me, that everything in your building, every vibe in the building has to be bent towards the environment and the feeling that you’re trying to create.

The main thing about culture is that things have to match up. Your statements, your values, your selection of people, the people you bring in – all that stuff has to sort of be bound together by a coherent philosophy.

Okay, let’s hear the last two principles.

Resilience. Nobody succeeds a hundred percent. The best clutch shooters in the NBA don’t even make 45% of their shots. Failure is an essential precondition for success. Athletes and coaches are a bit like engineers or tech guys in the sense that they understand that an interesting failure breeds future success.

It’s your tolerance for setbacks, your tolerance for failure, and then your willingness to attack that failure in a very organized, analytical way and make incremental personal or organizational improvements. It’s failing with purpose.

Finally, intention is like that last magical bit of animation. I mean, athletes aren’t robots. We’ve all had experiences where we watch athletes who almost seem to fly. And it’s not just a physical manifestation, it’s that they love what they do. They’re fully a hundred percent invested in what they do. And when you have that, that’s when things can really elevate. Saying, ‘I’m gonna give everything I have to this. And I may not be the best in the world at it, but I’m going to feel a sense of completion from having given everything I have to it.’

You write about embracing what we do as something we all should do with our work, how so?

Look at these great coaches, like Pat Summitt. She coached for 38 years, Kerry, and she won eight championships. Now, that was a lot of championships. But 30 years, she went home a loser. If it was about winning, she couldn’t have done it. She wouldn’t have been happy. She loved her work more than anyone I’ve ever known. She loved coaching. She loved teaching. She found real meaning and purpose in it, even when she lost.

People who have successful lives and successful professions have purpose and meaning in their life, so that even when they hit a roadblock or they suffer a setback, they know why they’re doing it, and they can feel good about themselves and how they’ve conducted their business.

What is the common thread of all the high performers you have met?

They all care more about the overall endeavor than their own personal status. The happiest I ever saw Michael Phelps was when the USA team won relays. He was plenty happy for himself, but he had a special joy on relay teams. You see that in golf where you see players compete in the Ryder Cup with an intensity of feeling. You see the same thing in tennis too, with the Davis Cup.

What is the one magic ingredient you write about that is not one of your seven principles?

Curiosity. That’s what striving really is. Who am I? What is this? What can I do with it? Can I get better? Can I find a way not to get worse as I age? Striving is good for people.

Kerry Hannon is a Senior Reporter and Columnist at Yahoo Finance. She is a workplace futurist, a career and retirement strategist, and the author of 14 books, including “In Control at 50+: How to Succeed in The New World of Work” and “Never Too Old To Get Rich.” Follow her on Twitter @kerryhannon.