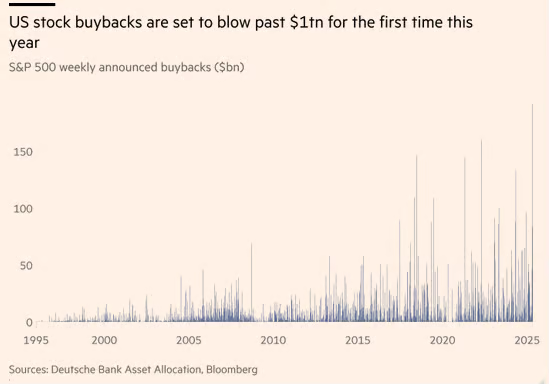

1. Buybacks in Last Month $518bn — the biggest rolling three-month sum on record, FT reports

FT.com

2. Last Month was Fewest American M&A Deals Since 2009

Reuters.com

3. Ethereum Bounces 40% Off Lows

The Market Ear

4. Bitcoin ETF Making Run at Highs

Stock Charts

5. Trump’s crypto dealings are jeopardizing a bipartisan stablecoin bill

By Filip De Mott for Business Insider

- Democrats are pushing back on a bill that has been seen as an easy win for the crypto industry.

- The stablecoin bill has lost bipartisan support as Donald Trump pursues various crypto ventures.

- Democrats are pushing anti-corruption measures focused on crypto.

President Donald Trump’s crypto ventures are getting in the way of his own agenda.

Pushback has grown as Trump and his family dabble in a range of crypto endeavors.

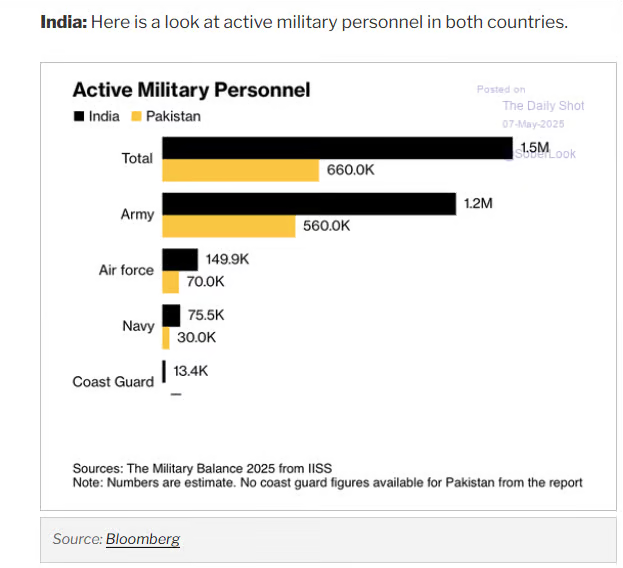

6. India vs. Pakistan Military Size

Daily shot Brief

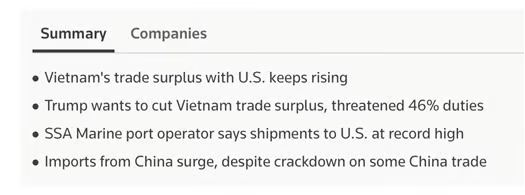

7. China to Vietnam to U.S. Trade Route

Reuters

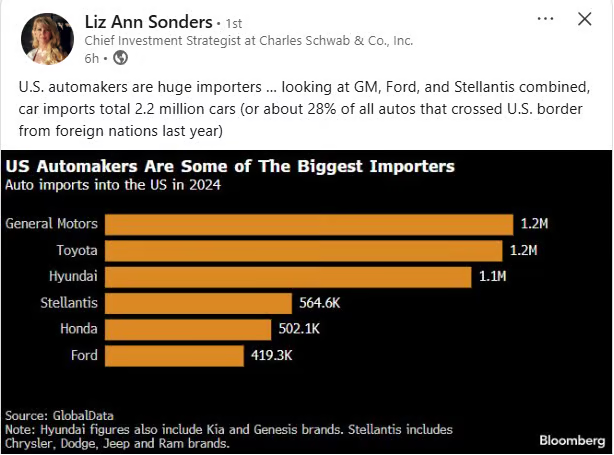

8. U.S. Automakers are Huge Importers

Liz Ann Sonders

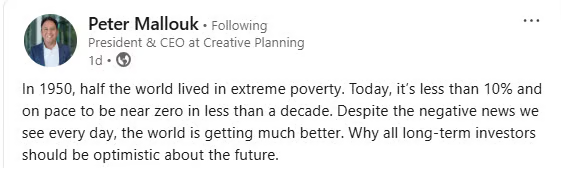

9. 50% of World in Poverty to 10%

Peter Mallouk

10. Opinion: 7 life lessons from Warren Buffett that have nothing to do with picking stocks

We all have the ability to emulate the Oracle of Omaha in the ways that really matter By Brett Arends

I’ve been following Buffett and writing about him for a quarter-century, which is long by some measures and no time at all by others. (He has been managing money for nearly three times that long.) Now that he has announced, at age 94, that he is at last retiring as CEO of Berkshire Hathaway, there are all the usual encomia about his investment genius and his stock-picking skills. And those are extraordinary, no question: It is very unlikely we would see his like again, even if we lived 10 lifetimes.

But it’s all the other stuff that has really struck me over the years — the smart decisions about life and money he’s made that don’t get so much attention. And that’s a pity, because those who try to replicate Buffett’s investment success probably won’t succeed. But everyone can learn from the other stuff.

1. He never moved to New York. Buffett never left Omaha, Neb., where the cost of living is a fraction of New York City and the quality of life, for him and probably for most people, is going to be much higher. (Bankrate reckons the cost of living in Omaha is 60% below that in Manhattan — meaning someone in Omaha need only earn $40,000 a year to have the same standard of living of someone in New York with an income of $100,000.)

Compare and contrast with all those people paying through the nose to live in a nice home in an expensive locale, or living in a shoebox, or spending 90 minutes commuting each way. Employers are now pushing everyone back to the office. Fair enough. But how about if more employers moved their offices somewhere more livable and affordable? It’s not the office that workers hate so much as the commute.

2. He didn’t waste money on stuff. Not for him the yachts, expensive cars, luxury properties or other toys of the rich and bored. Buffett seemed to understand early and instinctively what it has taken psychologists decades to conclude: That beyond a certain level, more spending will add little or nothing to your happiness. (When giving away his money, he said that spending beyond about 1% of his net worth on himself and his family would add nothing to their well-being or happiness.)

Psychologists refer to “the hedonic treadmill.” This is the futility — hence “treadmill” — of trying to achieve happiness by constantly buying more and bigger and better stuff.

The problem is that the human brain adapts to whatever we have. We get used to it. This is why lottery winners typically end up no happier years later than anyone else, and why if you visit a place where really rich people hang out — Palm Beach, Fla., or a five-star luxury hotel — and look around, you probably won’t see them all grinning madly about the fact that they are rich and marveling at all the things they can afford. But while “stuff” is costly to the rich, it’s lethal to the rest of us: That’s money we will need. The only way to beat the treadmill is to get off it.

3. He has a job he loves. From a financial standpoint, Buffett hasn’t had to work since he was in his 40s, but he kept going for another half-century — and loved it. “I’ve always worked in a job I love,” he once said. “I loved it just as much when it was a big deal if I made a thousand bucks, and I urge you to work in jobs you love.” Another time he described his job more as “play” than “work.”

This is priceless advice. Most of us will spend most of our waking hours, for the bulk of our lives, either working, traveling to or from work, getting ready for work or recovering from it. What is the dollar value of that time? It was a wise person who first observed that if you do a job you love, you’ll never work a day in your life.

Tailor your MarketWatch experience to your needs. Update your interests to help us recommend the most relevant MarketWatch features to you.

4. He has given, and is continuing to give, most of his money away. It’s almost impossible to imagine all the good that will be achieved with the hundreds of billions of dollars that Buffett has accumulated during his lifetime and that he is giving away to good causes. “Were we to use more than 1% of my claim checks (Berkshire Hathaway stock certificates) on ourselves,” he writes, “neither our happiness nor our well-being would be enhanced. In contrast, that remaining 99% can have a huge effect on the health and welfare of others.”

5. He didn’t care what the crowd thought. After more than a quarter of a century of writing about markets and finance, I’ve come to think my main expertise — possibly my only expertise — is on the subject of “popular delusions and the madness of crowds.” From ancient Greece to the COVID-19 crisis, it’s a subject that has fascinated me. And learning about it has made me especially fond of Buffett.

It wasn’t only during the dot-com bubble that he stood against the crowd’s insanity. He closed down his first partnership in the 1960s rather than join in the bubble of the “go-go years.” He invested, and publicly urged others to invest, during the epic bear market of the 1970s. He did it again during the 2008 crash. He made his money by courageously standing up against mass insanity and sticking to his principles. Bravo.

6. He’s humble. I’ve always said I don’t trust anyone until I have heard them say “I don’t know” and “I was wrong.” Buffett’s willingness to do both has been among his greatest and most profitable attributes. He has frequently emphasized that he invests only within his “circle of competence,” meaning he only invests in what he knows. And he admits there is a lot he doesn’t know.

“During the 2019-23 period, I have used the words “mistake” or “error” 16 times in my letters to you,” he wrote to stockholders in the 2024 Berkshire Hathaway annual report. “Many other huge companies have never used either word over that span.” For them, he added, “it has generally been happy talk and pictures.”

7. He’s acted like a grown-up. Can you imagine Warren Buffett standing around on a stage (in a graphic T-shirt) waving a chainsaw in the air and laughing about the middle-class jobs he was going to eliminate? Can you imagine him bragging about using bankruptcy laws to stiff his creditors? Can you imagine him running a bank so recklessly that it would end up crashing the global economy, but cashing out of his own stock before the stuff hit the fan, and then walking away with a shrug? I can’t. But I’ve seen billionaires and Wall Street tycoons do exactly those things in the recent past.

If you want to see how a billionaire should behave — in my view, anyway — watch Buffett’s remarkable statement to Congress during the Salomon Brothers hearings in 1991. There are billionaires, and then there are billionaires. We have too many of one kind, and too few of the other.