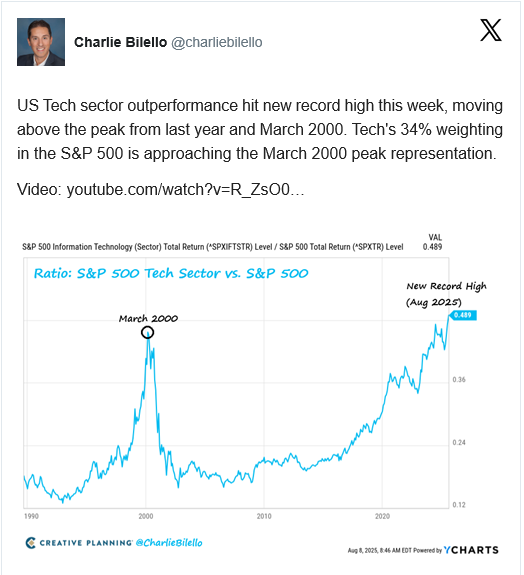

1. S&P Tech Ratio to S&P Above 2000

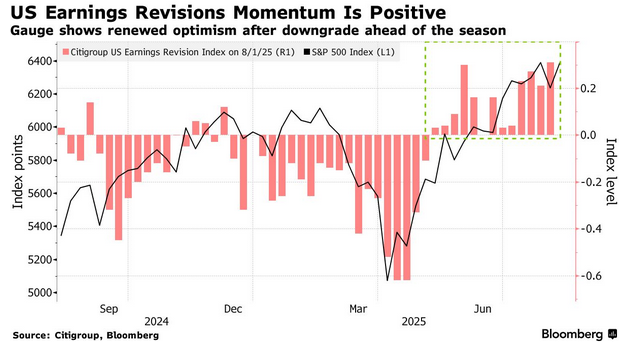

2. Analyts are Revising Earnings Higher.

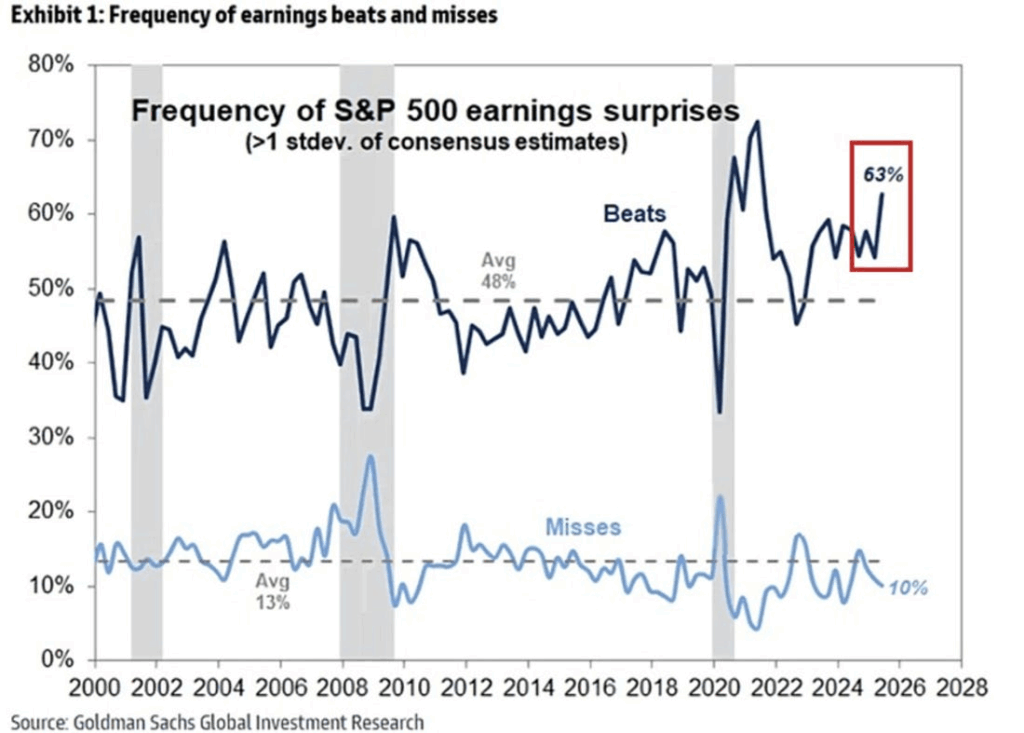

3. 63% of S&P Beat Consensus Earnings Estimates.

Earnings Surprise! And if you want something to support that, here’s one interesting stat; 63% of the S&P 500 beat their consensus earnings estimate by at least 1 standard deviation. Now to be fair there is a bit of gaming around earnings estimates (companies talk down prospects to analysts to try lower the bar for outperformance — you can see this potentially becoming more endemic over time with big beats trending up and misses trending lower to sideways). But even still, this is a notable datapoint.

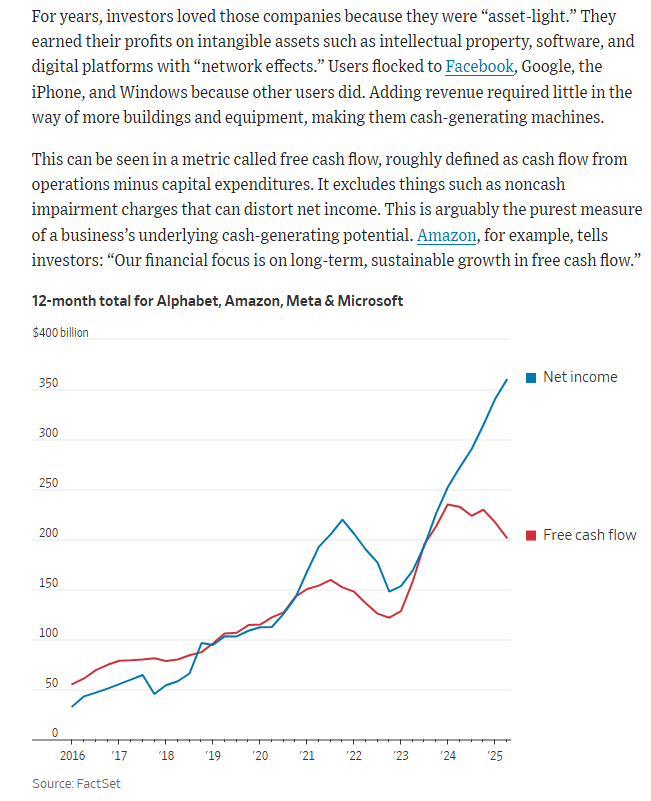

4. Free Cash Flow Slowing Down Due to Huge Capex Spends.

By Greg Ip-WSJ

https://www.wsj.com/economy/the-ai-booms-hidden-risk-to-the-economy-731b00d6

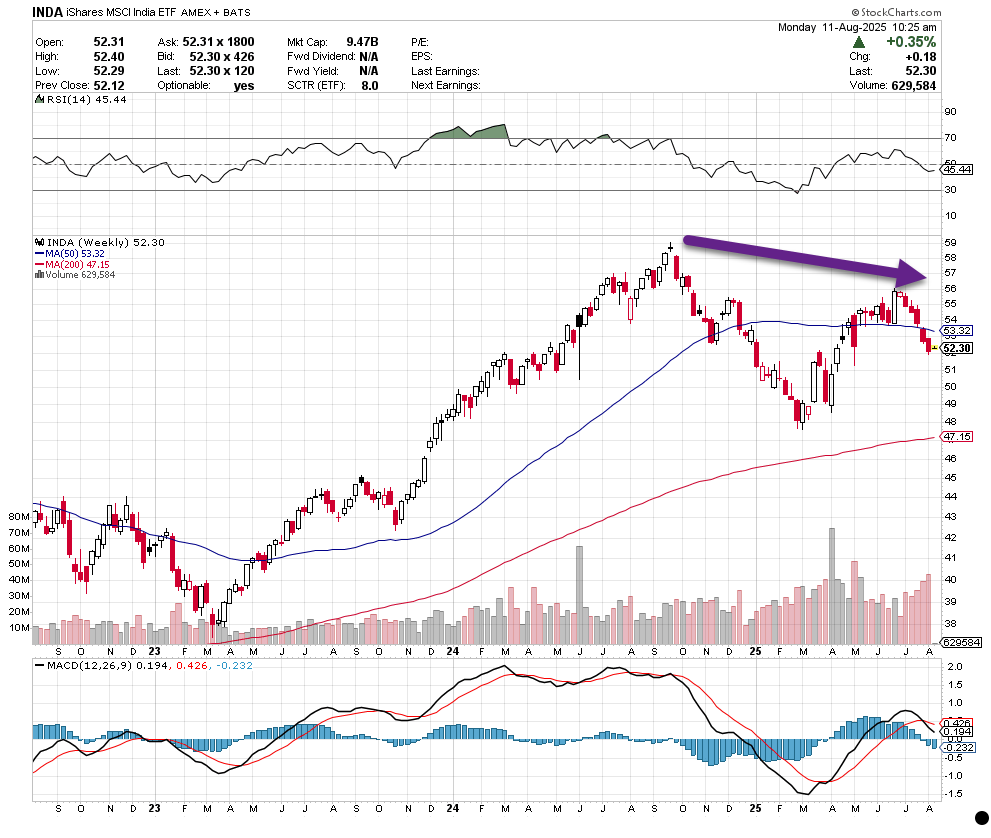

5. India ETF Failing to Recapture Highs.

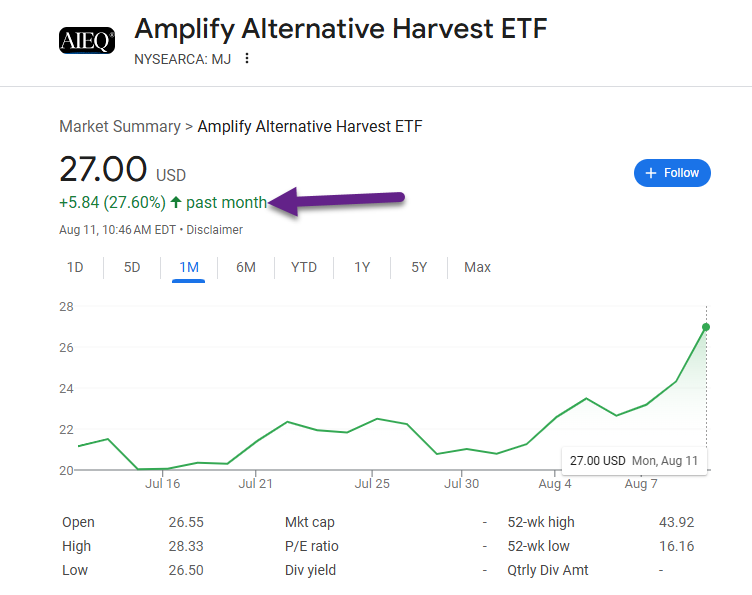

6. Trump Weighs Reclassifying Marijuana-ETFs Get Bump +28% One-Month

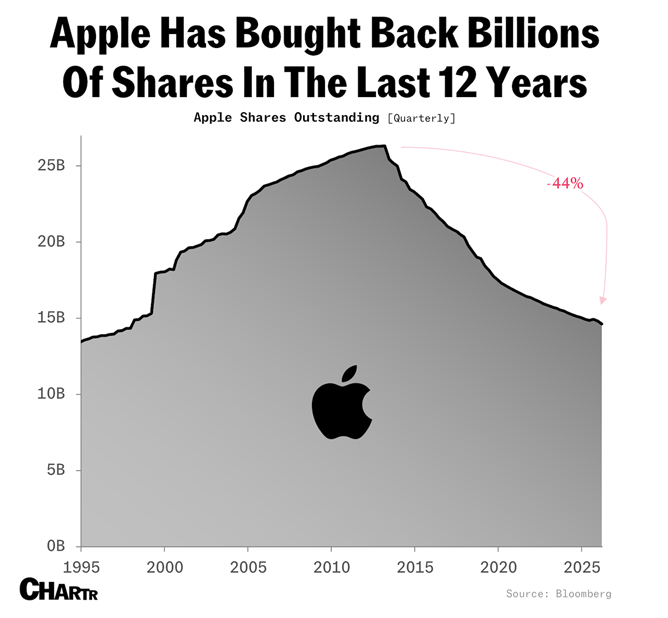

7. AAPL Has Reduced Its Share Count by 44% from Buybacks.

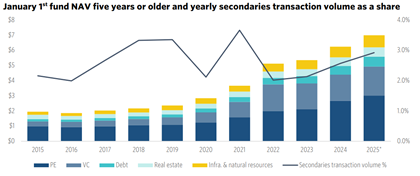

8. Secondaries are becoming second nature-Pitchbook

According to Evercore’s latest Secondaries Market Report, global secondaries transaction volume reached a record $102 billion in the first half of the year.

Once a niche strategy, secondaries have become a core part of the private capital toolkit, offering GPs and LPs alike a flexible, scaled solution for liquidity and portfolio management. LP-led deals made up 53% of total volume, reflecting steady demand from institutional sellers like endowments, foundations, and family offices.

Headline transactions such as Yale’s $2.5 billion sale and the New York City pension system’s $5 billion portfolio sale to Blackstone show how dramatically the market has evolved. What was once a quiet corner of alternatives is now handling transactions at the scale and complexity of large buyouts.

Meanwhile, GP-led deals totaled $48 billion, with multi-asset continuation vehicles gaining traction and syndication options expanding. These structures continue to adapt, balancing alignment with investor optionality and unlocking value from aging assets.

Still, the market is far from saturated. Our estimates suggest that secondaries activity represents only about 3% of total NAV held in funds older than five years, which is where most transaction volume is concentrated. That leaves trillions in legacy fund value as potential future deal flow.

Dry powder has kept pace, growing to an estimated $255 billion, up from less than $180 billion five years ago, based on our estimates. The pools of capital have also grown more specialized, with new strategies targeting credit, real estate, venture, and bespoke GP-led transactions.

In a slower exit environment, secondaries have increasingly become second nature and a central part of the private market landscape.

For related research, our colleagues in Europe have sized the institutional direct VC secondaries market at nearly $15 billion last year in a recent analyst note. Access prior editions of the PitchBook Weekly Commentary in our dedicated workspace.

Have a great weekend,

Zane Carmean, CFA, CAIA

Director, Quantitative Research

9. Renter Households Increase by 1.6M Since 2023

https://www.linkedin.com/in/ericfinnigan1

10. What Made Einstein a Genius Wasn’t His IQ

Psychology Today Why Einstein’s brilliance owed more to method, curiosity, and work than IQ. T. Alexander Puutio Ph.D.

Key points

- Raw intelligence is common; genius emerges when it’s systematically developed.

- We overrate talent because it’s visible and underrate the hidden work behind it.

- Genius can be cultivated through productive skepticism and deliberate practice, even if its a slow process.

Émile Zola, the French novelist, once quipped: “The artist is nothing without the gift, but the gift is nothing without work.”

The very same can be said about geniuses, and, in fact, it should be said much more often than it is.

Our fixation on thinking about intelligence as a feature induces a harmful kind of myopia that does nothing to help us run our engines better. When we look at geniuses like Einstein, what they had going on inside their craniums was only the beginning.

Think of it this way. If genius were a cake, Einstein would have had a bigger kitchen. What he still needed was the right ingredients, the right process, and the willingness to bake. And not just bake, but to make something exquisite.

The work, it turns out, matters much more than the raw brainpower. Without it, we would never have heard of Einstein at all.

Why intelligence doesn’t always germinate into performance

Intelligence is not as rare a commodity as we tend to think.

Statistically speaking, there are likely hundreds of Einstein-level minds walking among us today. There were likely just as many when our earliest ancestors roamed the plains, when their collective intelligence amounted to little more than sharper bits of obsidian and an improved way of roasting meat.

When thinking about geniuses of yore, we often fall for a post-hoc fallacy: We see extraordinary people and their accomplishments, and we attribute those accomplishments entirely to the intelligence they harbor. What we don’t see is the grind behind the scenes and the years of reading, tinkering, failing, and recalibrating, and the failures they’ve left behind. We underweight the work, and in doing so, we miss the true lesson that the rare glimpses of true genius we see could teach us.

Psychologist Françoys Gagné offers a useful lens for why we don’t generate more Einsteins and da Vincis than we do. He divides human abilities into two broad categories: natural abilities and systematically developed ones. We tend to notice the first, the obvious talent, but the second is invisible to us. That invisibility creates the double bind where we overemphasize natural talent because it’s salient, and we underemphasize systematic development because it’s hidden. As a result, we copy the wrong things.

Worse still, those who do find their way to systematic development often struggle to explain it to others. In fact, we often keep them as far away from teaching their methods as we can, and only want to hear of the outcomes instead. Einstein and da Vinci are perfect examples.

What Einstein and da Vinci actually did differently

Einstein, though widely revered today, was no star student in the conventional sense. He disliked rote memorization and distrusted the authoritarian style of teaching that had been passed down since Comenius coined the term didactics in the 17th century.

Instead, he gravitated toward teachers and peers who matched his yearning for independent thought. One such influence was his “Olympia Academy,” a self-made discussion group with fellows Maurice Solovine, a philosophy student, and Conrad Habicht, who was a mathematician and Einstein’s neighbor. Together, they read voraciously across fields, debating philosophy, science, and literature. They weaponized curiosity for no other reason than the joy of it, and that’s how Einstein first encountered Ernst Mach’s The Science of Mechanics, along with other concepts without which we would not be talking of his genius today.

For da Vinci, the formative influence wasn’t in books but in pure, unstructured experimentation. In Andrea del Verrocchio’s workshop, he learned a restless, cross-disciplinary way of working where switching from sculpture to painting to hydraulics without warning; leaving projects half-finished when a new obsession seized him was the norm. Pope Leo reportedly sighed, “Alas, this man will never finish a thing,” while Michelangelo openly mocked him for his unorthodox approach to work and learning. But that habit of wandering into new domains was precisely what fueled da Vinci’s breakthroughs.

In both men, you see the same threads: non-orthodoxy, early exposure to experimentation, and an almost aggressive curiosity. The same pattern runs through Richard Feynman’s safe-cracking physics, Alan Turing’s chess-playing machines, and countless others.

And yet, when we try to “recreate” genius today, we do the opposite. We hand out standardized textbooks, map out linear career paths, and treat curiosity as a distraction rather than the primary fuel for what we hope to come out at the end. Good luck to all involved.

Could you become a genius too?

The question isn’t as naive as it sounds.

We dismiss the thought because we’ve bought the myth that genius is a feature, an inborn gift, rather than a result. Many will even tell you that geniuses are born, not made. But the truth is that genius is cultivated, and, better yet, the cultivation process is accessible to almost everyone.

Adopting productive skepticism and weaponizing your curiosity will build a mind capable of surprising things. Even if your engine runs slower than Einstein’s, remember: This is not a race. Einstein himself took decades to reach his greatest insights, and in some cases, he was wrong.

A good place to start is the work ethic. You can borrow the tools, try your own thought experiments like Einstein, and explore fields you know nothing about like da Vinci. You could even chase ideas you have no immediate use for, just to create space for lateral thinking in the future.

I can’t promise you’ll solve quantum dynamics any better than Einstein did, but I can promise this. If you commit to the same kind of practice, you’ll end up in the rarest labor pool of all, the fellowship of people who are doing the work that creates genius. And that, more than IQ points, is what changes the world.